Ada M. Patterson – in conversation with Rachel Hann

Ada M. Patterson, A Ship of Fools (2020), 3-channel digital music video installation, video still. Courtesy: the artist & Copperfield, London.

Ada M. Patterson (b. 1994, Bridgetown) is an artist and writer based between Barbados, London and Rotterdam. She works with masquerade, performance, poetry, textiles and video, looking at the ways storytelling can limit, enable, complicate or abolish identity formation. Her recent work considers grief, elegy writing and archiving as tools for disrupting the disappearance of communities queered by different experiences of crisis. Recent exhibitions include Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 1950s – Now (2021-22) at Tate Britain.

Rachel Hann is a cultural geographer interested in material cultures of scenography, trans performance and climate crisis. She is based at Northumbria University in the Department of Arts. Rachel published her first monograph in 2019, Beyond Scenography (Routledge), and more recently has been leading new projects on trans and nonbinary approaches to aesthetics. In 2013, she co-founded the international research network Critical Costume.

Rachel Hann: My main area is scenography – stage design, lighting design, costume, sound – mainly from a theoretical point of view. But I have a real interest in costume. When I saw your work, immediately, it said ‘costume’ to me. There are many clearly defined costumed characters, from the tentacle-faced Bikkel (2019), to the plant-like Rammelaar (2019). In the videos, these characters all seemingly exist in our world (the shopping centre, the beach, the mangrove, etc.), but also produce their own world through their failures to fully appear in our own. They also seem to resist their own material and social identities, often existing in nonbinary ways – especially in terms of gender and the (non)human. Would you describe the things that you wear as ‘costumes’, or is there another language that you draw upon to describe these characters?

Ada M. Patterson: For me, I’ve sometimes used the word costume, but not in a very charged way. The word that I prefer to use is ‘masquerade’, but thinking about that in a more all-encompassing way. Like the way that the word ‘mas’ is used in an Anglophone Caribbean way, it is obviously pointing to the word ‘masquerade’, but it also encompasses the entire body: not only what the person is wearing, but also the music, all the collective activity, of being in the same space during carnival. The procession element, all of this is ‘mas’: all of the spirit and energy dedicated to crafting all of the costumes, the floats, the installations... The word ‘mas’ tries to encompass all of that within it. I’ve clung to using masquerade, because it feels a bit more spacious and hospitable.

I ended up making video works that document what might look like performances, but they are also documenting masks and costumes and bodies and stories and poetry, and sometimes music and landscapes. Video for me became a way of translating that mas spirit, of trying to hold all of this in the same space. I don't think it is entirely successful, but it's the best I can do so far. I tend to use the word ‘masquerade’, because it has a history and in places like this, one actually wants to have a history.

Rachel Hann: In terms of the installation, how are the videos of your work normally installed in the space?

Ada M. Patterson: With these smaller videos, I’ve shown them in a basic conventional set-up using projection screens, for instance. Most recently I made a larger work, which was a three-channel video installation, like a music video installation. It was called Ship of Fools (2020) (Fig 1). It was the first time I tried to think about video on a spatial level. Also, it wasn't my writing that was being used for the piece’s narratives, but writing that I commissioned from friends and loved ones responding to their experiences of climate crisis: between Barbados (Ark Ramsay), Australia (Clementine Edwards), and the Netherlands (M. Maria Walhout), each responding to their own individual embodied and located experiences of climate crisis. They each wrote their own texts. For me, I wanted to treat them as lyrics, even though I didn't ask them to explicitly write songs, and I played steel pan to provide the harmony, and I worked with another friend, Nicole Jordan, a vocalist based in Rotterdam, to try to sing the words. We worked together to make these songs out of these pieces of writing, and those were made into these music videos which were part of this installation. But, for me, the work was meant to be a vessel that you could inhabit, and for these words and experiences to be experienced through the viewer and not just watched but to actually, literally, physically, sit in it. The space was an embrace in the way that it was set up, and you were sat in the Centre of it, moving around as the song played across each screen.

Fig. 1: Ada M. Patterson, A Ship of Fools (2020), 3-channel digital music video installation, video still. Photo: Aad Hoogendoorn. Courtesy: the artist & Copperfield, London.

Rachel Hann: What is the starting point for your work?

Ada M. Patterson: Usually the starting point, where something takes form, is drawing. Here is a drawing of the first character that I made into material. It's the basis for Barbados Mulatto Girl (2020) (Figure 2), which is a response to an 18th-century print by Agostino Brunias, which has the same title. So, I started with this drawing that was responding to this colonial print, and after drawing it, I wrote a script for this character.

Fig. 2: Ada M. Patterson, Barbados Mulatto Girl (2017), graphite and color pencil on paper. Courtesy: the artist & Copperfield, London.

Sometimes the script comes before or after the character (the order shifts sometimes). But I wanted to write more of a sense of voice and personhood into this character, who was just very simply, reductively, named ‘Barbados Mulatto Girl’, which was a name for where she was located, the shade of her skin, and her gender. Also, at that time, I was researching ’visards’. Those black bits of velvet that were worn in, I think, the 16th century, by white Western European women in the 16th century. They have two eye holes in them, and they were used to protect the skin so that these women wouldn't burn or darken in the sun.

Fig. 3: Ada M. Patterson, Barbados Mulatto Girl (2020), performance. Photo: Lisandro Suriel. Courtesy: the artist & Copperfield, London.

I was really interested in those objects, not necessarily for their original function, but as an object that I felt looked really complicatedly beautiful, and I wanted to rethink the function of the object. I was really getting sick of this issue of having different parts of my body, or where I come from, being used against me. I wanted to find a way to make myself a bit opaquer, or to be able to talk about things without having all of that meaning literally inscribed on my body. And so, Barbados Mulatto Girl was my first way of approaching that dilemma.

Rachel Hann: I’m fascinated by the vizard. They're haunting. It's such a deep dark midnight that's on the face. And without a nose, without a mouth, and these two eyes. I’ve not seen this before, this is fascinating.

Ada M. Patterson: Yeah, so I first made the mask. Throughout this process, I’ve been gradually teaching myself how to sew. I’m self-taught in the sense that I’m taught by YouTube. That’s been a really fun process of learning, and also learning to be at peace with the fact that it’s probably going to be a bit crap or threadbare and raggedy. But I’m enjoying just being at peace with that. For me it began as this process of trying to make myself more opaque and illegible, protecting myself from these categorizations and inscriptions, and also to speak back to them on some levels, because this whole character was very much speaking back to the person who first painted her and also to the society that branded her ‘mulatto’ and as having yellow skin. She’s not wearing the vizard because she's ashamed of her skin colour; she’s wearing it so she can’t be read by other people. She’s this indeterminate, opaque, almost monster-like figure, because she can’t be read, and that’s terrifying in the face of a society whose entire enterprise is being able to read or being able to categorize one another.

Fig. 4: Ada M. Patterson, Bikkel (2019), digital video. Filmed by Kamali van Bochove. Courtesy: the artist & Copperfield, London.

Rachel Hann: I’m interested in the leap between the Barbados Mulatto Girl and the iconography that’s visible with Bikkel (2019) (Figure 4), where there are tentacles, a jacket, and sequins. It feels like it’s similar, but it’s also a departure from the Mulatto Girl character. Can you talk more about that?

Ada M. Patterson: With Bikkel, I had this moment. I was reading the writing of Audre Lorde and thinking about the idea of softness and vulnerability as a point of power or a point of agency. The image of the sea urchin has actually been present in a lot of my work, before I more actively started making these characters and masks. And I was using it as an image of protecting myself from this issue of being misread or exploited or extracted and being this thing that is visually beautiful, but dangerous to touch. I reached an impasse in thinking about the cost of embodying that brittle hardness. What is that doing to me, and how far can you really go staying in this position of constant vigilance and resistance and refusal and total opacity? How long can you actually survive living like that?

These questions, in retrospect, are also wrapped up in a lot of concerns that I’m working through around gender, and hardness and brittleness also in relation to masculinity as well. And so, reading into these ideas of softness and vulnerability as points of agency helped me to think through and ask: ‘well, what does a soft shell sea urchin look like’? In relation to Bikkel, that mask actually started out as a sculpture. So, I made this sea urchin using this sequin fabric, and I stuffed it with some polyester stuffing. And it’s just this object, which I then eventually unmade. I dissected it, scraping out the insides of the base. But I scraped it out in order to make a mask out of its husk, in a sense.

I really enjoyed making Bikkel, because I didn’t have a drawing with that character. I just had a few different ideas, which I was playing with materially. So, at that point, I had moved to Rotterdam where there’s this metro station in the south, Zuidplein, near where I live. It’s this large brutalist space. It’s grungy and grimy and there’s a lot of young guys around there. I find the biggest fashion in Rotterdam is different kinds of tracksuits. It’s very much that style and these guys just enjoy posing around the space in their finest tracksuits. I was really fascinated by this performance, and this very particular masculinity being performed with and for each other. I felt the need to queer that a bit, or to see the queerness that was already there in it. I was also fascinated by the fact that tracksuits, which are actually very soft, comforting, warming, and, in a sense, vulnerable pieces of clothing, could embody this sense of hardness or masculinity, this toughness as well. It was interesting that a soft material could do that, or was being made to do that – but also seeing the contradiction at play there, and I wanted to hold onto that. I wanted to make a response to a tracksuit using this more hypervisible material of sequins and textures.

Rachel Hann: Can you talk more about the relationship between that space and gender?

Ada M. Patterson: I think it was interesting for Bikkel to be in that space, because Bikkel is my idea of someone who’s failed masculinity, or masculinity has failed him. It’s like trying to don these clothes and trying to perform these bodily gestures of masculinity, like having a certain gait in your walk or little things like how far apart your legs are when you sit or stand. Little things like that, which are sometimes barely visible or extremely visible depending on who’s looking. Someone trying to learn those gestures, but not really being able to perform them entirely correctly, but also having those expectations projected onto the body of this person with this character, and again speaking back to an inscription of these things, reckoning with the fact that it is a painful experience to have those expectations weighing down on you, and not being able to fulfil them either. Or not wanting to fulfil them. Or trying to, failing, and asking: What are you left with?

Rachel Hann: Do you imagine these characters basically existing in the same artistic universe?

Ada M. Patterson: I don't think they’re related for the most part. At the same time, they might share an experience that transcends and transgresses where they are located, just like the frames of those places, in the sense that I think they occupy the same planet, in as much as I am someone who also felt the pain of being projected onto. And I’m sure that there are loads of other people who are not, say, in Barbados, or whatever, but across the other side of the world, who have also felt that in different ways. This confrontation with a society that has an enterprise of naming things and accounting for things and categorizing things, I don’t think that’s unique to this place. I think that’s very much a colonial apparatus. So, I think these characters exist in the same world in the sense that I exist in the same spaces as other people who I might not know, but who I might share a certain experience with. Of reckoning with that first pain of misreading, misrepresentation, or being made to fit into something that can’t hold them.

Rachel Hann: These characters seem to be slowly building up a sense of a place that isn’t this place, but another place. That these are characters are trying to, as you say, mould themselves into this world – but at the same time failing.

Ada M. Patterson: Yeah, and when you’re actively not fitting into this world, what world is the rest of you leaking into? With Bikkel, his whole deal is that he’s lived through these expectations of masculinity, and then he’s accounting for this experience of being softened. He’s survived this masculinity, or he’s barely survived it in the sense that he’s entirely closed off. His face has turned into spikes and he’s this hard little sea urchin who eventually softens. He’s still living with the residues of what it meant to survive those projections, but yet the wound is scarred into something else, something more liveable, I guess for him. But this concern with the shared pain of that experience… It eventually caught up with me that I was just reproducing and projecting the pain that I experienced onto these characters. I thought, wow, they must have a lot of resentment for me, because I’m re-inscribing that pain in order to figure something out for myself, which I don't think is right, for them at least. Which is why, with the character Rammelaar—

Rachel Hann: This is the ‘green bush’ person, yeah?

Fig. 5: Ada M. Patterson, Rammelaar (2019), digital video. Filmed by Kamali van Bochove. Courtesy: the artist & Copperfield, London.

Ada M. Patterson: Yes! Rammelaar (2019) (Figure 5) came about after realizing this potential resentment that these characters might have for me, and thinking that the thing that I’m striving for myself is all of these layers of complexity, complication, and multiplicity. Not having to be fixed in any certain direction and being able to move quite fluidly, and for that to be the aspiration and the dream. And yet, I’m fixing these characters in the place of the harm that they’ve experienced. And that feels a bit awful. For me, Rammelaar was this idea of trying to make this character that even though their Silhouette was fixed, in a sense of being this, you know, this green bush character, that their surface could change and could point to somewhere else that wasn’t necessarily under my control. That’s my sense of the narrative behind the character, what I imagined their life has been. I don't know what their life is, but I know that they’ve walked away and just entered the wilderness. And they’re just living in that mess, where they can hide or be seen at will.

Rachel Hann: That was certainly one of the most striking things for me. Where the other characters were hyper visible within their environment, Rammelaar felt like it could recede as well as appear, almost like Bigfoot. There was a vibe of ‘let’s blend in’, let’s be with, let’s meet these other species, these other plants, these other life cycles on their own terms, rather on more human terms. Do you see Rammelaar as being more than human?

Ada M. Patterson: I think that’s a good question. So, for me, the category of human is never really useful. Also, coming from this space of colonial inheritance, where ‘human’ is such a shaky category for people who historically didn’t have space in that category, I don't know if it’s like walking away from the sense of what it means to be human, or just learning how to be more than human, or just learning to be other things among being human as well. I’m not really sure where I stand on that entirely. But all of that is to say it’s shaky, and I don't know.

Rachel Hann: ‘Shaky’ is a good way of putting it. The character in Mangrove Village (2018) (Figure 6) is especially interesting in that regard as they’re basically dead. They're a corpse, hidden in the mangrove, but these other species are now living on, with and through this corpse. Whereas the other characters had become very much alive, the Mangrove Village character is seemingly dead. How does the idea of death work within this narrative universe?

Fig. 6: Ada M. Patterson, Mangrove Village (2018), live performance. Documented by Avery Butcher. Courtesy: the artist & Copperfield, London.

Ada M. Patterson: I would say with Mangrove Village that the character isn’t necessarily dead. I would say that their pace has been slowed to a point where it very much looks like they’re dead, and I imagine that character with very different intentions, but I want to reflect on it in a different way now. Because it was imagined when it was the 50th anniversary of independence here in Barbados, which doesn't really mean much. It means something, but I don’t think it means as much as it is trying to. Anyway, there was a rise in gun crime and gun violence around that time and I just couldn’t help but notice how surprised a lot of people seemed to be about it, even though these things happen after every few years or so, or generationally. It was like trying to speak back to a sense of a very unstable cultural memory, which seems to forget every so often, and not being able to learn intergenerationally, but also seeing the arrival of changes as a threat or a surprise, which is not easily handled or received or dealt with in any generative way. And so, I imagined this village, which was so afraid of change it stayed still, it stayed the same, so much so that it crystallized, turned swampy and sunk into a mangrove. And so that character actually is a response; its anatomy is a response to a folk character here in Barbados called the ‘shaggy bear’, which has its origins in West African folklore characters. I think it has a counterpart in Jamaica: a character called Pitchy Patchy.

Rachel Hann: Yeah, I’ve seen a Brazilian artist do something similar.

Ada M. Patterson: Yeah, this character exists under different names and different functions across the region, I think. Originally in Barbados, it was made out of dried banana leaves and cane trash, and so it was actually quite horrifying – the sound of scraping leaves against gravel – but also with a different movement… The movement it embodies now is very fast, very agile and acrobatic. The character does lots of leaps and things like that. So now, it’s this character that’s characterized by this fast-paced movement, and I really wanted to slow it down completely. Also, this was around the time that large clumps of sargassum seaweed started arriving on our shores, and began complicating and hindering the tourist industry and the fishing industry, and was immediately seen as this problem that we had no way of dealing with. It really rubs me the wrong way, because every time difference arrives, it’s seen as a problem. And every time change arrives it is seen as a problem, and not seen as something that we can actually hold onto and make space for. I wanted to embrace that problematic material of seaweed and think about it in relation to this character. This character moves at a glacial pace. Before actually performing, the character was in the space completely still, not moving for three hours before he gets up to speak, and then returns to a still position. In retrospect, what I enjoy about that character is that there’s so much life hidden in them, so much different life, which I didn’t really account for when I first made the character. I’ve been thinking a lot about sargassum seaweed as a material, but also as this climate-crisis-related phenomenon. It harbours so much life in it, like bacterial life, different marine animals, plankton and other things, as well as the sargassum itself as a living entity. It also has this weird function of accumulating all the plastics and garbage in the oceans and brings it ashore. I’m really interested in it as a material right now, because of these strange capacities.

Rachel Hann: I’m keen to ask you about the ecological throughlines in your work. In particular, your responses to the seaweed coming up on shore and its relationship to climate change. What is causing them to come up on to shore?

Ada M. Patterson: So, the seaweed already existed. What is seen as the issue now is that warming waters are making it flower and bloom a lot more intensely. And I think in places like the Caribbean, how climate crisis is experienced is that it takes what we already have and makes it more intense, be that seaweed, or the intensity of hurricanes, or the intensity of droughts. It’s like it’s this untenable overabundance of what we already have. And so, the seaweed is growing at this rate, it sometimes reaches a point where you can go to certain shores, certain beaches in the island, and it will just be filling the water, whole waves of seaweed. And it’s really beautiful and disturbing.

Rachel Hann: So, you could say that the seaweed is flourishing? I mean it’s literally flourishing. Ecologically it’s succeeding. An interesting context but that idea of climate crisis, bringing over abundance to the Caribbean islands, I think that’s really interesting.

Ada M. Patterson: At the same time, the issue with that is if there’s too much of this seaweed it does take out the oxygen from the water. Usually, it can be this floating community of all these different kinds of lives and species, but when there’s too much of it, it becomes a floating graveyard. And when it piles up on the shore, it’s said to absorb the nutrients from the soil and sand, and so it becomes a lot to deal with. It doesn’t mean that there’s no life living; it just means that life is either different or more scarce, depending on which part you’re looking at.

Rachel Hann: Is the plan to harvest the seaweed? How can it be managed in an ecological way? It feels quite difficult to manage.

Ada M. Patterson: I think some people are trying to use it as fertilizers. I’m not sure what else they’re using it for yet, but we definitely don’t have it the worst compared to islands like Martinique, who had so much of it that it filled entire beaches and the waters around them. I know a lot of artists are using it for performances and things. What I find interesting about this material now is that, also in relation to the plastics, it takes everything that has been thrown into the ocean and spits it back up in this weird vengeful way. The only issue I have with that, though, is that most of these plastics are not necessarily coming from the Caribbean; they're caught in the Atlantic swirl from other places. It’s an example of how climate crisis and its consequences are experienced disproportionately across the world.

Rachel Hann: Yeah, the excesses of countries such as the UK are being felt in island nations in the Caribbean. The felt injustice.

Ada M. Patterson: At the same time, I wanted also to bring it back to thinking about bodies and these strange characters and figures. For me, there’s a question in there… When the seaweed arrives on the shore, how do places or some societies deal with undesirable things and bodies? How do we treat those, how do we hold them, and can we make space for them, or are we not prepared to do that? And how are they seen? What will we do with the undesirables? I feel a weird kinship with the seaweed.

Rachel Hann: I wondered if you considered your work in terms of the grandiose nature of ‘world’ and of ‘infinity’? From the grains of sand, the looking out to the ocean horizon... Does that resonate?

Ada M. Patterson: There’s a sense of infinity if you live on an island and you’re looking out to the horizon, and you can’t get across it by yourself, you don’t have the means to and can only imagine what’s beyond the horizon. It’s that infinity which also leaves you yearning to move beyond what you can’t cross or fathom, and to access those things which are hidden from you. And in terms of thinking about portals that are sometimes in my work, I can achieve it through green screen effects and keying localized bits in the image. For me it’s the digital magical means by which to cross horizons. To go somewhere else, to be somewhere else, even though I can’t be there and this is the only way I can travel right now, or this is the only way I can be transported, by using this this tool of the green screen effect.

In one of the other works – Looking for 'Looking for Langston' (2019) (Figure 8) – there’s also this moment where this Captain character is holding this square of green screen, which shows a conch shell being held. That part was filmed in the Netherlands, and at that time I needed a conch shell, and I didn’t have a conch shell. So, I needed to just leave space for a conch shell until I was able to go back to Barbados to do the rest of the film. I’m not able to go there yet, and so right now, this Captain will have to live with this green square of card. But when I’m able to I can fill in that space for myself and for him. It’s this delayed filling in of the dream or the fantasy or the aspiration to be transported. On a logistical level, it’s like I need this thing, and I can’t access it here, so I need to make space that can be filled in a different way. And I need a portal to do that, so the keying becomes that.

Fig. 7: Ada M. Patterson, Looking for ‘Looking for Langston’ (2019), digital video. Still by Koes Staassen. Courtesy: the artist & Copperfield, London.

Fig. 8: Ada M. Patterson, Looking for ‘Looking for Langston’ (2019), digital video. Still by Koes Staassen. Courtesy: the artist & Copperfield, London.

Thinking about infinity, it’s linked to this idea of the portal as well, because as long as I know how to make a portal, I can go anywhere, even if I physically can’t go somewhere. And for me it’s like holding on to that idea to also be hopeful of what is possible: hopeful in terms of what can be imagined for a body, how a body can change, and where a body can go or relocate. How can I reimagine my surroundings as well? It’s thinking of those questions and holding on to an infinite number of possibilities to give myself the most space for, firstly, transportation, but also transformation. To know that the possibility is there to be everywhere, but also to be everything. Which goes back to this idea of being with other worlds and species, that I don’t have to be stuck or stranded anywhere. I don't have to be fixed. That infinity is possible, if I just let it in. Or let myself dissolve in it.

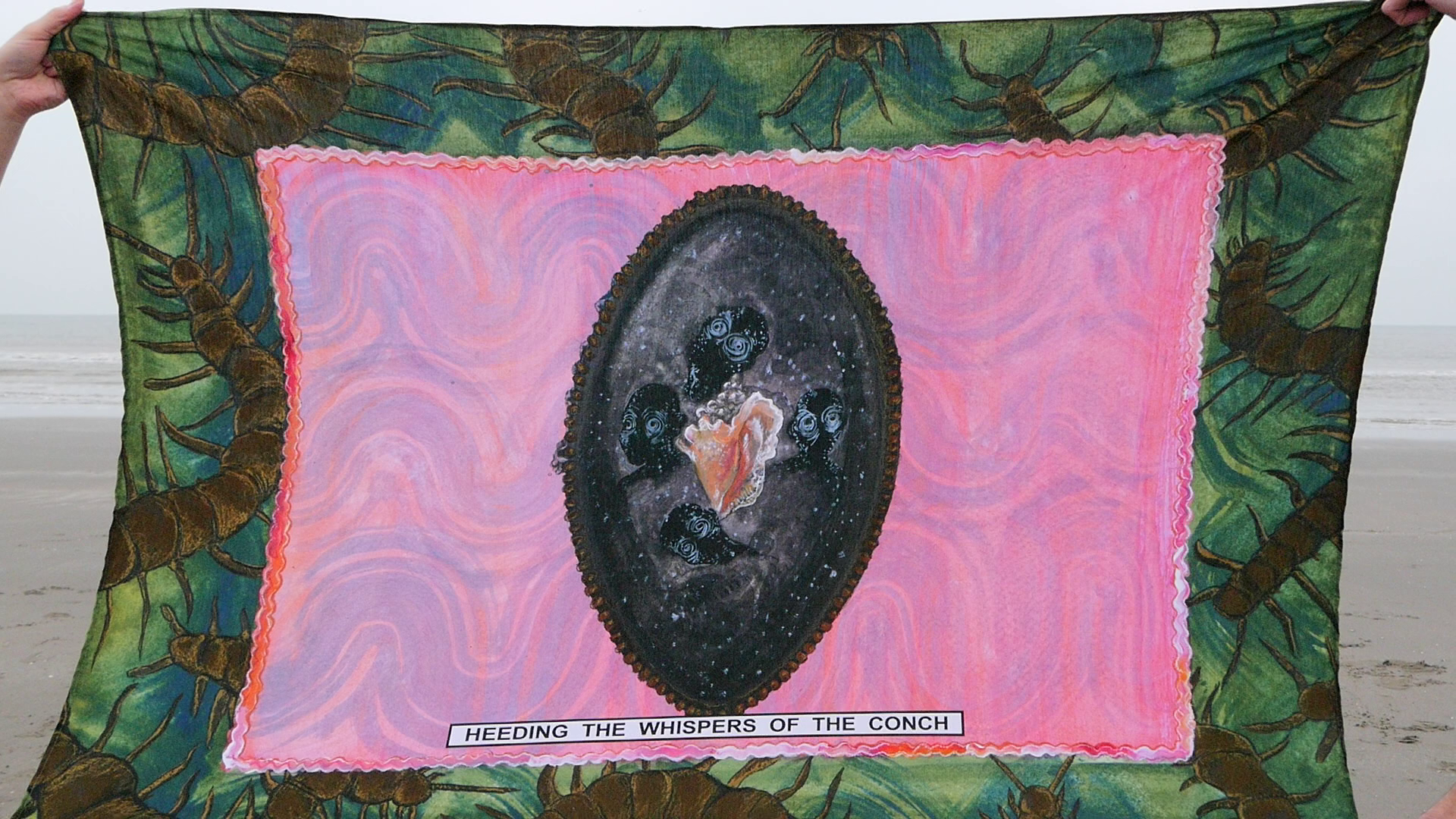

Rachel Hann: Yeah, I really liked that. Letting yourself dissolve in the infinity and to be with the overabundance. Could you speak a bit more about that use of the fabrics (Figure 9) in A Ship of Fools and The Whole World Turning, because I read them as flags. Is that a fair reading?

Fig. 9: Ada M. Patterson, Kanga for the Present (HEEDING THE WHISPERS OF THE CONCH) (2019), inkjet on cotton, as seen in The Whole World is Turning, digital video. Courtesy: the artist & Copperfield, London.

Fig. 10: Ada M. Patterson, A Ship of Fools (2020), 3-channel digital music video installation, video still. Courtesy: the artist & Copperfield, London.

Ada M. Patterson: Some people have called them flags, but they’re actually ‘Kanga’, which is a textile that’s popularly worn in East Africa. I inherited them through my mother, who’s from Kenya. Growing up, we had these more traditional kangas in our house that we would wear casually, you can wear them around your waist, hair or torso. I’ll speak a bit more about them and then we’ll talk about why I use them. What I find interesting about them is that they are wearable textiles, but also that they’re communication devices. They’re characterized by the central images, border, and then this message, which is also the name of the kanga. And they’re usually written in Swahili or Arabic. I haven’t really seen many written in English. They are gifted to other people very intentionally. And this can be in a ceremonial way to honour a wedding proposal between families, for instance, or it can be a criticism or threat, things like ‘pride goes before a fall’.

Essentially, the kanga is this multilateral device for expressing something and communicating something which is intended for the wearer. I find them really fascinating because of that function. And I love that there’s not a lot of space to say something; there’s only so much that can be printed with the kanga. And I started making these small Kanga drawings during the passage of Hurricane Dorian in 2019 through the Caribbean.

I started drawing these kanga sketches, trying to imagine what little words I could, for what was happening. And at times I couldn’t even find my own words. Some of them are taken from song lyrics and things that speak to not only the sense of crisis, but what was being salvaged from these moments of crisis. These strange intimacies, kinships, relationships and different kinds of love being made during a hurricane. It was a departure for me to think, how can I say this without writing a whole script for it? So, after the sketches, I started printing them larger on cotton because it’s also this idea of being able to wear it, to wrap a loved one up in this protective, sheltering cloth.

Rachel Hann: And how many of the kangas did you have printed?

Ada M. Patterson: In The Whole World Is Turning (2019) there’s four. And then in A Ship of Fools there’s three. For A Ship of Fools, each kanga was made with one of my collaborators in mind, and then a copy was gifted to them. It says, ‘How can I honour your words that you’ve given me’, ‘how can I give you some means of shelter’, and ‘how can I imagine something for you that is helpful in this world where help feels a little scarce’. Especially with A Ship of Fools, it was very much this confrontation with the idea that this thing is happening, bodies are disappearing, whole worlds are disappearing whether by flood, drought or fire. And a lot of these lives will not be grieved. How do I respond to that? Because I can’t solve climate crisis. I’m just an artist. But the thing that I felt I could do was make space for this grief, for what felt like a grieving for un-grieveable lives.

Rachel Hann: Do you see your work through a gendered lens, and if so, what terms do you use to describe it?

Ada M. Patterson: So, there’s obviously times that I’ve used gendering, like with Bikkel, and with Barbados Mulatto Girl, in very deliberate ways… Talking about what it means to be gendered and to have gender put upon you. Also in ways that you don’t necessarily agree with, or that are not fulfilling for you. With some of the other characters, I just assumed that they don’t have genders or they haven’t told me. With the characters in Buchibushi (2019) and Rammelaar, their gender is not important to who they are. I started thinking about Rammelaar, very much thinking about this process of green screening and digital keying as a means to change one surface, to transform and to be whatever you wanted to be. I started giving these workshops, Slippery Surfaces, which involved activities like green paper cutting, with live digital keying happening as we’re handling this material. We also used green felt for masks and costume making – but all through this digitally-keyed lens, generating footage and images that participants might want to insert into their keyed bodies, supported by different readings that disrupt easy and stable notions of gender, race, sexuality etc. How do we slip out of our surfaces, how do we slip on these surfaces, and how do we make our surfaces slippery?

Fig. 11: Ada M. Patterson, Buchibushi (2019), performance, digital video. Photo: Sharelly Emanuelson. Courtesy: the artist & Copperfield, London.

Rachel Hann: It is a lovely metaphor, more than a metaphor, because it makes them slippery.

Ada M. Patterson: Yeah, so around the time that I started that project, it coincided with me disclosing that I was feeling a non-binary-ness. For me, this idea of nonbinary was never an identity in itself. I didn’t want it to be a category. I’ve seen it become a category, which I’m happy with if that’s fulfilling for other people, but it’s definitely not fulfilling for me. Gradually, trying to live through that just became more and more scarce. Being perceived by cis people and their perceptions and understandings of gender for themselves, it became this very scarce enterprise, where they would think: ‘Oh, so you're nonbinary, so you’re this other fixed thing’. Then it becomes this point where I’m defending, where I’m dying on this hill of they/them pronouns. But that’s not what it was about. I’ve been misled to this place. And so, more recently, I’ve been coming to terms with what it means to do the work of trans-ing.

In retrospect, thinking about all these characters, thinking about some of them being deliberately gendered or ungendered, it’s like: was anyone going to tell the trans girl in the room what she was doing? Of course, I was making characters! Of course, I was trying to figure this stuff out through different kinds of embodiment! It has always been about trying to figure out my own capacity for change. The knowledge that I can change and that I don't have to be stranded. And thinking back to the other characters, neither do they. It’s been interesting going back to look at them and to think, in a trans way, what was going on here? Or in a non-binary way, what's going on here? What do I do with that, if I need to do anything with that?

Rachel Hann: Yeah, I think non-binary-ness lacks cultural reference points. Representation affords legitimacy, but also first legibility. In the political forum, one of the things I was really interested in with regard to your work was the way in which it was pointing towards what I might describe as ‘non-binary ways of thinking’ about world. For instance, the character Rammelaar is non-binary with the environment, as they’re both human and non-human at the same time. Interestingly, both of the characters that you mentioned as being ‘ungendered’ are also more than human in some way. This idea of understanding non-binary experience as being equally about rethinking our relationship with environment/world/non-human is for me a cultural reference point that is lacking.

Ada M. Patterson: I think what all the characters share is that they have absorbed their environment. For better or worse, for whatever that means to them. And so you obviously have Bikkel and Barbados Girl absorbing certain expectations of colour, gender and sexuality, but then you have characters like Buchibushi and Rammelaar who are in their own environments absorbing that, but also being dissolved into that. To think about the non-binary-ness of that, say for Bikkel, if you’re living in a binary society, of course you’re going to absorb that binary-ness and its consequences.

Rachel Hann: And yet still be evidently not doing X.

Ada M. Patterson: Or not knowing how to.

Rachel Hann: Trying in some respects, but also failing. Not being X.

Ada M. Patterson: Yeah, when I say absorbing, it’s like being vulnerable to those things, to those surroundings and environments. One’s body responding to, being permeated by, or having those things go inside you and change your body, whether on a cultural level or a chemical level. And I’ve been thinking a lot about this lately in terms of hormones and things like that. What are the things that I consent to taking inside of myself in order to change myself? And not only on this deliberate chemical level, but what are the things in my environment that I want to take in and allow to change who I am, what I look like, and how I live? Rammelaar is letting not only their environment but also their surface change so much that it points to a different location while remaining present inside their own body. It’s all these things that they’re carrying inside, and I think the difference with Rammelaar (compared to a lot of my other characters) is that Rammelaar gives me hope. The hope for dreaming up characters that can consent to these changes, and to holding these particular spaces of discreet illegible possibility inside themselves.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Nicola Roberson for the transcription of this interview.

Support

If you would like to support Ada, please do consider contributing to their GoFundMe page.