Dancing decadence: Salomania

Dr Adam Alston – Goldsmiths, University of London

Fig. 1: Deadly and addictive. Advertisement for perfumed cigarettes, featuring Maud Allan. Monochrome print published in Broadway Brevities, 1 (6) (December 1921), p. 2. Public domain.

The poet and critic Arthur Symons, who was a key exponent of aestheticism and decadence in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, describes dance as ‘that natural madness which men were once wise enough to include in religion, [beginning] with the worship of the disturbing deities, the gods of ecstasy, for whom wantonness, and wine, and all things in which energy passes into an ideal excess, were sacred’.[1] The ‘natural madness’ that I suspect Symons had in mind in writing this was probably that induced by the Dionysian Mysteries, which was an ancient rite that stimulated a trance-like ekstasis (ecstasy) through a mixture of psychoactive intoxicants, ceremonial acts, and communal dance. It was also a rite that appealed to demographics marginalized by the Ancient Greeks, including women and slaves, and that the state tried – but failed – to suppress (in fact, Dionysianism was later incorporated as a state religion). Around the time of the fin de siècle, when Symons was writing, the dancing bodies of women – especially foreign bodies, both ethnically foreign, and regarded as biologically and morally infectious – were similarly demonized as a toxic influence on the health and moral fibre of a nation. In addition to forming ‘part of the fabric’ of its production and reception, the perception of dance as a natural madness provided a screen for a repressed (male) society to project ‘cultural tensions surrounding women, the body, and the body’s relation to mind’.[2] And not just the body and the mind. These tensions pertain as much to the perceived decay of a ‘decadent’ society. Such is the argument put forward in this post, which focuses on a raft of Salomes who danced their way from the boards of nineteenth-century Parisian cabarets to those of early-twentieth-century music halls in the United States – and from there into the pages of the newspapers, where ‘Salomania’ seemed to take the form of a veritable epidemic.

This is one of a series of posts I’m gathering under the title of ‘Dancing Decadence’. The first was a discussion of the Norfolk rave scene, the second looks at the Weimar dancer and enfants terribles Anita Berber, and a forthcoming post is going to be looking at ‘Disco-mania’ in the 1970s. Although you can find discussion of Salomania elsewhere on this blog, in a great guest post by Megan Girdwood, it seemed to me that no such series would be complete without covering this topic, and especially the pioneering and innovative contributions of its most famous figurehead: the Canadian dancer Maud Allan (Beulah Maud Durrant), who made her name in Europe in the early nineteenth century, before falling foul of conservative vitriol that had a devastating impact on her livelihood. This post, then, is intended to honour Allan’s work as a dancer, the contexts in which she was dancing, the sources that probably inspired her, and the ‘Salomanian’ legacy that she, in turn, inspired. It is addressed primarily to those yet to encounter her practice and influence.

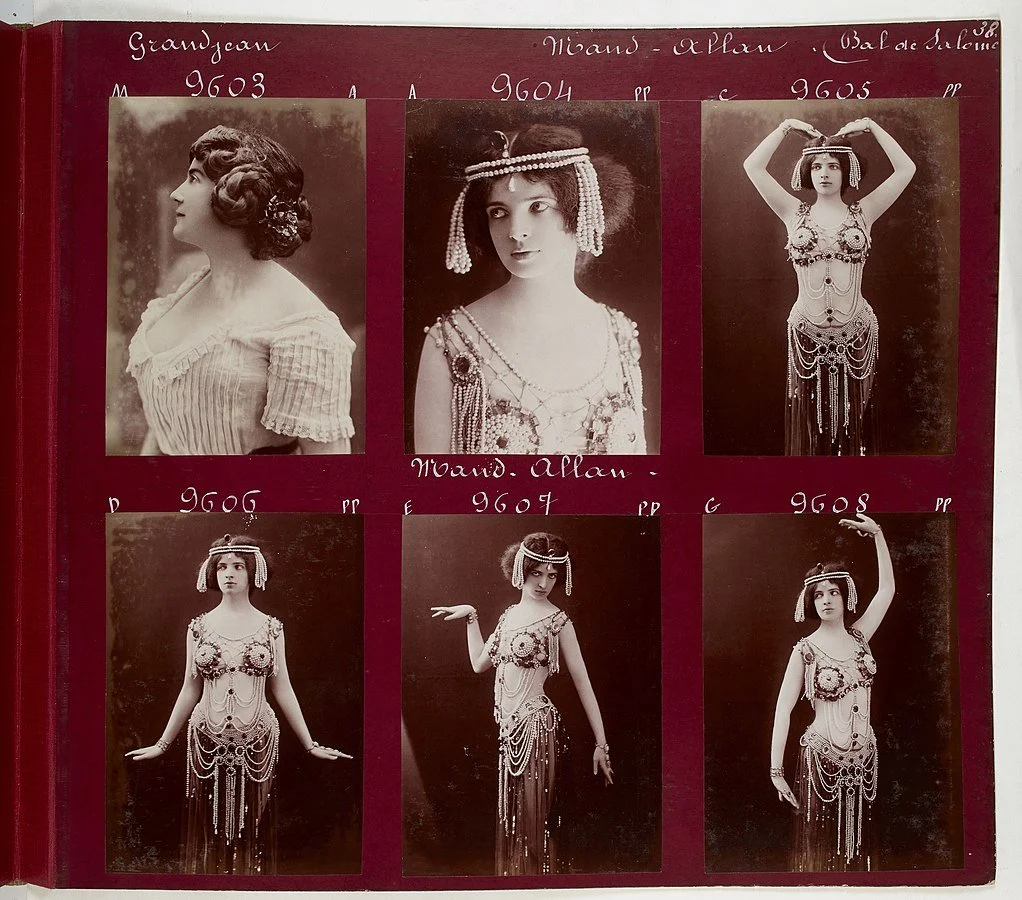

Figs 2 & 3: Jean Reutlinger, various photographic portraits of Maud Allan, including depictions of Salome. Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Estampes et photographie (46bis). For a comprehensive selection courtesy of Gallica, click here.

Salomania is most readily associated with the rapid spreading of dance performances between 1906 and 1910 in Europe and the United States that were based on the Biblical story of Salome, although they owed a greater debt to the controversy surrounding Oscar Wilde’s play Salomé (1891), particularly following his conviction for ‘gross indecency’ in 1895, and the popularity of Salome acts devised by Loïe Fuller and Maud Allan between 1895 and 1907. Wilde wrote Salomé in French while living in Paris in 1891, and it is an early example of an English writer entering the nascent world of symbolism associated with Stéphane Mallarmé and Maurice Maeterlinck. However, as Petra Dierkes-Thrun acknowledges, who is a key scholar of the play’s performance history, the scandal that came to surround the work was not really concerned with its high-minded symbolism, so much as ‘a decadent tête-à-tête’ at the play’s climax, in which ‘Salome earnestly addressed and then amorously possessed the severed head’ of Jokanaan (John the Baptist).[3] This is the most famous episode in the play: one of the ‘hallmark images of decadent femininity and its sadistic eroticism’.[4] The notoriety of this scene certainly added grist to the mill of the dancing Salomes, although the erotic ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’ that Salome dances to trick Herod into offering her the head of Jokanaan on a silver charger offered them a more explicitly choreographic template that inspired their own takes on this decadent ur-text.

European and North American Salomania at the turn of the twentieth century extends how performers in Parisian cabarets between 1870 and 1910 were responding to a nascent tranche of medical discourse associated with hysteria, epilepsy, neurasthenia, and St. Vitus’s Dance. Movements, gestures, and tics associated with these phenomena played into performance style and content, which, as cultural historian Rae Beth Gordon recognizes, were influenced by well-known physicians like Jean-Martin Charcot.[5] Sarah Bernhardt and the Chat Noir poet and singer Maurice Rollinat were known to have attended his ‘lessons’, and the Moulin Rouge dancer Jane Avril was once one of his patients, having been erroneously diagnosed with St. Vitus’s Dance: ‘a psychological condition’, as Catherine Hindson notes, ‘classified as one of the “dancing manias” that became central to the study of women and madness at the fin de siècle’.[6] As Gordon remarks of the Chat Noir, ‘convulsive body language and hysterical tics and grimaces there formed the basis for a new aesthetic in popular spectacle and in “high art”’, inspiring crowds to lose themselves in ‘the quadrille, or the wild thrill of the can-can, […] not unlike descriptions of St. Vitus’s Dance and “Tarentisme” noted in convulsive hysterical disorders’.[7] In other words, the contagious qualities of ‘hysterical’ dance, as experienced by crowds in Parisian cabarets, offers an important precedent for the emergence of Salomania as a phenomenon of the American music hall. Equally, these were not merely symptomatic acts; they were dynamic interactions with institutional and social contexts.

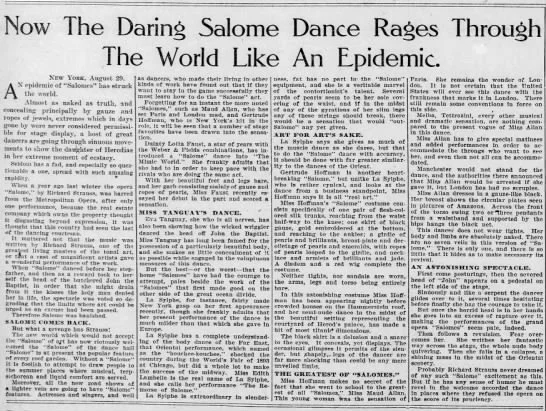

On 30 August 1908, The Sun (Baltimore) diagnosed an ‘epidemic’ of dancing Salomes, ‘[a]lmost as naked as truth, and concealing principally by gauze and ropes of jewels, extremes which in days gone by were never considered permissible for stage display […]. Seldom has a fad, and especially so questionable a one, spread with such amazing rapidity’.[8] Salomania presented a clear opportunity for women to make a name for themselves as performers, just as it might be understood as ‘an exuberant expression of female agency and sexuality transmitted from body to body and through the pages of mass circulation newspapers’,[9] as Marlis Schweitzer puts it. Indeed, Salome is no Giselle; she does not dance herself dead (although she is killed by Herod’s soldiers at the end of Wilde’s play), and nor does her love save the life of a deceptive lover. Rather, her pursuit of an uncommon pleasure – a key facet of decadence – transgresses a supposedly natural and acceptable order of feminine desire for Herod’s court, as much as audience members subscribing to such an order. As Schweitzer points out, the Salomania ‘craze’ also exposed deep-seated anxieties and prejudices concerning racial degeneration and the contagiousness of foreign bodies and practices – issues that the remainder of this section addresses by focusing on their entanglement with decadence as a pejorative concept that might also be reclaimed through choreographic and sartorial practice.

Fig. 4: The Sun, ‘Now the Daring Salome Dance Rages through the World Like an Epidemic’, The Sun (Baltimore), 30 August 1908, p. 24.

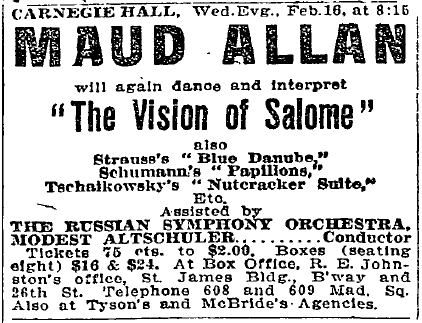

Gertrude Hoffman, La Sylphe (Edith Lambelle Langerfeld), Lotta Faust, La Petite Adelaide (Mary Adelaide Dickey), Aida Overton Walker, Eva Tanguay, and countless others built reputations and in some cases carefully-crafted infamy off the back of seductive dances with ‘gauze and ropes of jewels’. Their acts owe a debt to Loïe Fuller’s dance-pantomime Salome, which was initially inspired by Jules Massenet’s opera Hérodiade (1881) and performed in full in 1895 at the Comédie Parisienne, before evolving through a series of excerpted and more popular iterations to a more assertive 1907 performance of Robert d’Humières’s silent two-act drama La Tragédie de Salomé (1907).[10] However, Maud Allan’s Vision of Salomé (1906), based on Wilde’s play and very likely influenced by Fuller’s dance, is widely recognized as a key progenitor of Salomania, in some cases being explicitly plagiarized in derivative versions, with dance schools and private dance instructors offering pupils lessons in Allan-esque style. For instance, Hoffman was commissioned by theater manager Willie Hammerstein (through his agent Morris Gest) to ‘mimic’ the work in 1908.[11] The proliferation of derivative performances is unsurprising from a commercial point of view given the scandal surrounding Allan’s Vision, but her dance was initially considered relatively tasteful, received the endorsement of King Edward VII, and enjoyed a run of 250 sold-out performances at the Palace Theatre in London starting in March 1908 – the very same theatre, re-branded as a music hall, where a censored 1892 production of Wilde’s play starring Sarah Bernhardt was set to take place (the censor did not have jurisdiction over music halls, where dance versions of Biblical matter were permissible even if the plays were not).[12]

Fig. 5: Advert for one of several 1910 performances with New York's Russian Symphony Orchestra. New York Times, 9 February 1910, p.16. Public domain.

The salacious reputations of music halls as bastions of vice and degeneracy made them a prime target in the crusades of moral puritans. Allan herself described her body as the ‘raw material’ of her dances, and her famous costume was embraced by the women’s dress reform movement – both of which informed her association with British suffrage (a cause that Allan opposed in her writing, possibly in a bid to protect her career).[13] The Great War also had an important part to play in how Allan’s performing body was read and understood, as the notorious Pemberton-Billing trial goes some way toward illustrating. The trial was prompted after the independent member of Parliament Noel Pemberton-Billing published ‘The Cult of the Clitoris’ in a March 1918 issue of his right-wing newspaper, The Vigilante. The piece was a response to a production of Wilde’s Salomé by J. T. Grein’s Independent Theatre Society in London, starring Allan in the title role, and implied that the work was aiding the German forces by spreading moral corruption and degeneracy among the British public, building on Allan’s association with lesbianism in the satirical press (it is likely that she was gay or bisexual). Echoing the 1895 Wilde trials, Allan and Grein sued Pemberton-Billing for libel, but in doing so inadvertently provided him with a platform for condemning the propagation of a degenerate and antipatriotic homosexuality ‘cult’, further advancing the absurd charges of conspiracy and sedition already advanced in the Vigilante. For Pemberton-Billing, who was cleared of the charges against him, this was a fight against ‘cultural decadence’, and for the very soul of a nation at a time of existential crisis for the Allied forces.[14] Suffice to say that the court’s decision ruined Allan and Grein’s reputations and careers.

As Schweitzer observes, contemporary critics

warned that the proliferation of scantily clad Salomes would pollute the contained, corseted bodies of respectable women and corrupt the minds of men. Others worried that the vulgar dance would encourage the spread of immoral thoughts and behavior among immigrants, urban youth, and those vulnerable to cheap amusement. Still others maintained that the Salome dance would damage dancers’ internal organs and make them susceptible to hysteria, which in turn would induce similar forms of mental distress in female spectators.[15]

Even President Theodore Roosevelt was warned about the threat it posed to ‘national security’,[16] tapping into a range of anxieties ranging from male apprehension over the emancipation of women, to fears around ‘race suicide’ – the belief that white America was falling foul of declining birth rates and an influx of ‘diseased’ immigrants from eastern and southern Europe – and concerns ‘about theater’s role in the moral contamination of the youth’.[17] The dancing Salomes were therefore interpolated by narratives concerning disease, corruption, and racial degeneration, all of which tend to be landed upon in the conservative or reactionary diagnosis of societal decadence.

The fact that Salome was no mere femme fatale but a Jewish femme fatale was also crucial. It aligned fears around the appearance of a sexually powerful and potentially destructive woman with the anti-Semitic stereotype of an oversexed and diseased Jewess, here appearing as a foreign body capable of infecting and corrupting a susceptible nation.[18] Equally, these anxieties and apprehensions were reflected back to their interlocutors through corporeal and sartorial citation, exploiting and augmenting the tropes that aroused them in the hope of soliciting a sufficient level of salaciousness and potentially lucrative scandal.

The trial of white European and Canadian dancers, playwrights and directors on grounds of spreading moral corruption steals the limelight in studies of censorship, but in 1893 – much earlier than the Pemberton-Billing Trial and two years prior to the Wilde Trials – a group of young Ottoman dancers were arrested and charged with ‘performing a dance contrary to good morals’ – a danse du ventre called ‘Streets of Cairo’ – at New York City’s Grand Central Palace.[19] Critical reviews published in The New York Times dwelled upon the Turkish garments worn by the dancers, their body shapes, their prestige in ‘the Orient’, relationships with Eastern men of medicine, and the dance’s supposed licentiousness.[20] ‘Against the charge that the dance was “disgusting” and “indecent”’, writes Julie Stone Peters in her account of the trial that followed, ‘the defence asserted its value as art. As an “artistic dance and the dance of our nation” (said Zuleika [one of the dancers]), the dance “had a picturesque beauty” that “embodied the poetry of motion” [… I]t was, in effect, “art for art’s sake”’.[21] The dancers were released subject to a $50 fine, and returned to the theatre with a dance that conscientiously upped the provocative ante. However, there was more than the ‘embodied poetry of motion’ on trial. If dance and theatre could ‘infect’ an audience, then that infection was emphatically embodied by an Oriental Other.

Like the danse du ventre scandal, Salomania also concerns what Rhonda Garelick describes as a ‘fascination of all things Oriental’ in both Europe and the United States, particularly with regard to ‘those women perceived as living Salomes, the seductive, often veiled “danseuses du ventre” imported from the colonies’.[22] Gustave Flaubert, Gustave Moreau, Joris-Karl Huysmans, and Wilde certainly succumbed to such fascination, who were all progenitors of decadent art and literature, as well as Salomania. Both those enamoured by or critical of the dancing Salomes tended to adhere to what Marjorie Garber describes as ‘a standard trope of Orientalism, a piece of domesticated exotica that confirms Western prejudices about the “Orient” and about “women” because it is produced by those prejudices’.[23] In other words, the embroilment of Orientalism in decadent art and literature and its transmission to the bodies of dancing Salomes participated in the proliferation of Orientalist practices and prejudices at the turn of the twentieth century.

Where Wilde’s Salome is crushed beneath shields at the play’s close, Salomanian dancers – despite the extent to which they played to male and Orientalist gazes – were also recognized as agents of social and cultural transformation. Hoffman’s semi-plagiarized act is a case in point, as Schweitzer recognizes, which ‘concludes with Salome’s sexual awakening. This Salome is not ashamed of her sexuality or body but rather delights in new discoveries’.[24] It is also notable that Allan’s most fervent supporters were women, many of whom comprised her core audience.[25] So there was more to the ‘societal craze’ surrounding their work than scandal; they were also role models invested with the capability of effecting social and cultural change.

Fig. 6: Gertrude Hoffmann as Salome, with head of Jokanaan, 1908. Photo by F. C. Bangs. Public domain.

Finally, Salomanian dances do not just succumb to puritanical fears about societal decadence. In playing to and with spectatorial ill-ease, and the fears and desires co-mingled in the decadently dancing body, they perform the possibility of dismantling the master’s house. This is far from a radical undermining of the patriarchy that derided these spectacles, and that underpinned their choreographic and sartorial orientation. Their employment of Orientalist imagery was also the consequence of careful calculation, augmenting exotic tropes in full awareness of how such imagery would be received and scandalized. The Salomanian dancers, then, were both caught and complicit within the propagation of complex cultural-political tensions: they were subject to derision as ‘decadent’ and ‘degenerate’; they were dependent upon salacious figurations of exotic Others and all of the fears and anxieties around corruption, contagion and infection that they aroused; but they were also capable of exploiting (and not just be exploited by) the ‘decadence’ and ‘degeneracy’ of which they were accused. In short, Salomanian dancers embodied the cultural politics of decadence: subject to, complicit within, and capable of subverting its pejorative connotations as a social and moral disease.

Notes

[1] Arthus Symons, Studies in Seven Arts (London: Archibald Constable and Company Ltd., 1906), p. 387.

[2] Felicia McCarren, Dance Pathologies: Performance, Poetics, Medicine (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998), p. 13.

[3] Petra Dierkes-Thrun, Salome’s Modernity: Oscar Wilde and the Aesthetics of Transgression (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011), p. 44.

[4] Megan Girdwood, ‘Salomania and The Russian Disease’, Staging Decadence Blog, 6 September 2021, https://www.stagingdecadence.com/blog/salomania-and-the-russian-disease, accessed 17 February 2023.

[5] Rae Beth Gordon, Why the French Love Jerry Lewis: From Cabaret to Early Cinema (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001).

[6] Catherine Hindson, Female performance practice on the fin-de-siècle popular stages of London and Paris: Experiment and advertisement (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2007), pp. 89 and 108.

[7] Gordon, Why the French Love Jerry Lewis, pp. 60 and 95.

[8] The Sun, ‘Now the Daring Salome Dance Rages through the World Like an Epidemic’, The Sun (Baltimore), 30 August 1908, p. 24. Available at: https://img8.newspapers.com/clip/24241332/the-baltimore-sun/, accessed 17 February 2023.

[9] Marlis Schweitzer, ‘The Salome Epidemic: Degeneracy, Disease, and Race Suicide’, in The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Theater, edited by Nadine George-Graves (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 890-921 (p. 892).

[10] Fuller presented less salacious excerpts of the 1895 piece – La Danse du feu (the Fire Dance) and Le Lys (the Lily Dance) – at the 1900 Paris Exposition. ‘In Fuller’s hands’, writes Rhonda Garelick, ‘Salome undergoes a progressive metamorphosis: from a dangerous femme fatale to chaste child and then to a nameless vision of flame and flowers’ (Garelick 2007, 103). However, when she revived the piece in 1907 as La Tragédie de Salomé, ‘the chaste virgin had gone: this Judaean princess was unquestionably a femme fatale’ (Hindson 2007, 196).

[11] Schweitzer, ‘The Salome Epidemic’, p. 898.

[12] Dierkes-Thrun, Salome’s Modernity, pp. 88-89.

[13] Dierkes-Thrun, Salome’s Modernity, pp. 97, 101-02, and 106-07.

[14] Dierkes-Thrun, Salome’s Modernity, pp. 111.

[15] Schweitzer, ‘The Salome Epidemic’, p. 891.

[16] Cahill qtd. in Dierkes-Thrun, Salome’s Modernity, p. 102.

[17] Schweitzer, ‘The Salome Epidemic’, p. 892.

[18] See Schweitzer, ‘The Salome Epidemic’, p. 898. Schweitzer highlights the subjection of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe to invasive screening processes at ports of entry into the US at the turn of the twentieth century. The immigrant Jewish population fleeing persecution in Europe were also blamed for cholera outbreaks in the 1890s, as well as scalp and eye diseases. See Schweitzer, ‘The Salome Epidemic’, pp. 895-96; see also Alan M. Kraut, Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the ‘Immigrant Menace (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994), pp. 105-35.

[19] Qtd. in Julie Stone Peters, ‘Performing Obscene Modernism: Theatrical Censorship and the Making of Modern Drama’, in Against Theatre: Creative Destructions and the Making of Modernism, edited by Alan Ackerman and Martin Puchner (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), pp. 206-30 (p. 206). Peters’s account is based on a number of reports published in The New York Times in December 1893.

[20] Peters, ‘Performing Obscene Modernism’, p. 206.

[21] Peters, ‘Performing Obscene Modernism’, pp. 206-08.

[22] Rhonda K. Garelick, Electric Salome: Loie Fuller’s Performance of Modernism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007), p. 92.

[23] Marjorie Garber, Vested Interests: Cross-Dressing and Cultural Anxiety (New York and London: Routledge, 1992), p. 340.

[24] Schweitzer, ‘The Salome Epidemic’, p. 900.

[25] Hindson, Female performance practice, p. 52.