Nero, or Rome’s first actor-emperor

Guest post: Dr. Shushma Malik, University of Roehampton

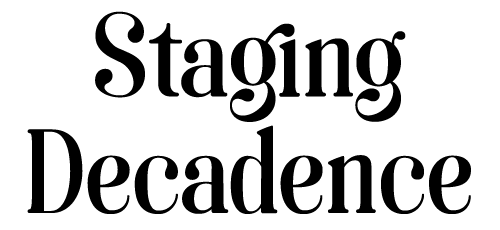

Fig. 1: ‘Nero, after the Antique’, by Jacques Louis Perée, with Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres serving as intermediary draughtsman, 1803/09. The etching depicts an (imagined) statue of emperor Nero, standing whole-length, and nude except for a drapery around his waist. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

I supplicate and pray to you for victory, preservation of life, and liberty against men insolent, unjust, insatiable, impious – if, indeed, we ought to term those people men who bathe in warm water, eat artificial dainties, drink unmixed wine, anoint themselves with myrrh, sleep on soft couches with boys for bedfellows – boys past their prime at that – and are slaves to a lyre-player and a poor one too. Wherefore may this Mistress Domitia-Nero reign no longer over me or over you men; let the wench sing and lord it over Romans, for they surely deserve to be the slaves of such a woman after having submitted to her so long. But for us, Mistress, be thou alone ever our leader.[1]

This fervent speech, given by Cassius Dio’s Boudicca to rouse the Britons into action, encapsulates brilliantly the controversy caused by the emperor Nero’s desire to act and perform on stage in the eyes of Roman historians. Nero, Boudicca claims, is so weak and effeminate that he may as well be a woman, and the people whom he leads (the Romans) are as corrupted by luxury as he is. The emperor makes slaves of citizens by playing the lyre (badly) and singing. Nero’s yearning to be an actor, singer, and musician were signals to conservative Romans that he was not the sort of man who should have been able to call himself a citizen, let alone ruler of the Roman Empire. Moreover, his theatricality, in the eyes of Cassius Dio, called Nero’s gender into question – situating the emperor in a fluid space between the masculine and the feminine.

Fig. 2: Alloy coin from Nero’s reign. The obverse depicts Nero’s head. The reverse depicts Nero playing a lyre in the flowing robes of Apollo Citharoedus. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

In stark contrast to today, actors in ancient Rome were infames, meaning they were ranked amongst the lowest in Roman society. Actors (all of whom were male) were distrusted because of their ability to fake emotions, to conceal their real feelings, and to play both gender roles in their performances. The Stoic philosopher and advisor to Nero, Seneca, described performers as those who ‘imitate the emotions, who portray fear and nervousness, who depict sorrow, imitate bashfulness by hanging their heads, lowering their voices, and keeping their eyes fixed and rooted upon the ground. They cannot, however, muster a blush; for the blush cannot be prevented or acquired’.[2] If an aristocrat were to choose to be an actor, he would need to lower his status through official channels. Young elites did sometimes take up this option if they had been bitten by the theatrical bug; for instance, according to Suetonius, Tiberius (r. 14-37 CE) put in place a law that saw these men exiled. For an emperor himself to tread the boards, then, subverted the norms of status and hierarchy, as well as those of gender.

Although he had loved the theatre and music all his life, Nero did not step onto a stage in public until 64 CE. When he does so, the historians depict his performances as blending real life and fiction. Nero is perhaps most famous today for being a tyrant and a murderer. So prolific is this characterisation that the current exhibition on Nero at the British Museum takes it as read that a large part of the audience will come in with this preconception firmly ingrained (the exhibition’s curators promise to reveal instead ‘the man behind the myth’). Some of the most atrocious of Nero’s alleged crimes are the murders of his mother Agrippina in 59 CE, his first wife Octavia in 62 CE, and his second wife Poppaea in 65 CE. The roles he most enjoyed acting on stage were ones that echoed these aspects of his biography (Nero chose to play Orestes, Thyestes, and Alcmeon because the plays’ plotlines involved famous instances of familial killings). Even worse, Nero used theatrical masks that explicitly called to mind those whom he was thought to have killed:

Yet why should one lament these acts of his alone … in putting on the mask [Nero] threw off the dignity of his sovereignty to beg in the guise of a runaway slave, to be led about as a blind man, to be heavy with child, to be in labour, to be a madman, or to wander an outcast, his favourite rôles being those of Oedipus, Thyestes, Heracles, Alcmeon and Orestes? The masks that he wore were sometimes made to resemble the characters he was portraying and sometimes bore his own likeness; but the women's masks were all fashioned after the features of Sabina [Poppaea], in order that, though dead, she might still take part in the spectacle.[3]

Fig. 3: 2nd century marble relief with tragic and comic masks. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

But, the real danger of Nero’s theatricality was not that he subverted norms by going onto stage himself to perform risqué roles. Rather, Nero’s reign was toxic because he turned every interaction in his life as emperor into a theatrical scene, with his family or members of the public as his players as well as his audience. For example, when Tacitus recounts Nero’s poisoning of his step-brother Britannicus (55 CE), he doesn’t just describe the act itself, but also the pretence set up by Nero to explain away the sudden death. The scene plays out, according to Tacitus, over dinner. Nero is angry because, when he goaded Britannicus into reciting a poem earlier that day, his step-brother had demonstrated a natural talent for the task. So, Nero met with his favourite poisoner, Locusta, and procured a potion for Britannicus’s drink. As the drug began to take effect, Nero claimed that Britannicus was suffering from an epileptic fit and both Nero’s mother Agrippina and his wife Octavia (who was also Britannicus’s sister) had no choice but to play along with the pretence, banishing their true knowledge and their true emotions in order to continue with the banquet. This episode displays what Tacitus sees as the brutality associated with Nero’s love of theatre – not only does the emperor act, but he expects all those around him to follow his script as part of their daily lives.

These episodes – Boudicca, Britannicus, and the masks – all highlight how Nero’s acting on the stage was characterised as going far beyond the antics of a young man wanting to rebel against normal royal protocol. Nero’s theatricality was part of his tyranny;[4] he used it to manipulate his family and to manipulate Rome, and he used it to make reality bleed into fiction and vice versa. In short, he used it to shock, to terrify, and to control.

Let’s now flash forward to the nineteenth century to examine how this Nero – the artistic performer and the tyrant – worked in the context of the fin-de-siècle, when both the emperor and decadence were very popular. The portrait painted in antiquity of Nero could not really have been more fitting for this period, as the multi-faceted nature of decadence (subverting social mores to the extreme) made the relationship between art and crime of the utmost interest. One of the most famous works to explore this relationship is Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891). Wilde himself modelled his haircut on a bust of Nero from the Louvre when he returned to Europe after a lecture tour of America in 1883. He professed to wanting to scandalise bourgeoise society with his new look.[5] In Dorian Gray, art and crime are intimately connected by the painting of Dorian, which carries the burden of displaying his decline into corruption via physical deformity. Further, in the middle of the novel, Dorian expresses his own desperate wish to be like Nero (or other infamous Roman emperors) because only then could he test the limits of artistic licence without any fear of the legal consequences:

There were times when it appeared to Dorian Gray that the whole of history was merely a record of his own life, not as he had lived it in act and circumstance, but as his imagination had created it for him, as it had been in his brain and in his passions. He felt that he had known them all, those strange terrible figures that had passed across the stage of the world and made sin so marvellous and evil so full of subtlety. It seemed to him that in some mysterious way their lives had been his own. […] he had sat, as Tiberius, in a garden at Capri, reading the shameful books of Elephantis, while dwarfs and peacocks strutted round him and the flute-player mocked the swinger of the censer; and, as Caligula, had caroused with the green-shirted jockeys in their stables and supped in an ivory manger with a jewel-frontleted horse; and, as Domitian, had wandered through a corridor lined with marble mirrors, looking round with haggard eyes for the reflection of the dagger that was to end his days, and sick with that ennui, that terrible taedium vitae, that comes on those to whom life denies nothing; and had peered through a clear emerald at the red shambles of the circus and then, in a litter of pearl and purple drawn by silver-shod mules, been carried through the Street of Pomegranates to a House of Gold and heard men cry on Nero Caesar as he passed by; and, as Elagabalus, had painted his face with colours, and plied the distaff among the women, and brought the Moon from Carthage and given her in mystic marriage to the Sun.[6]

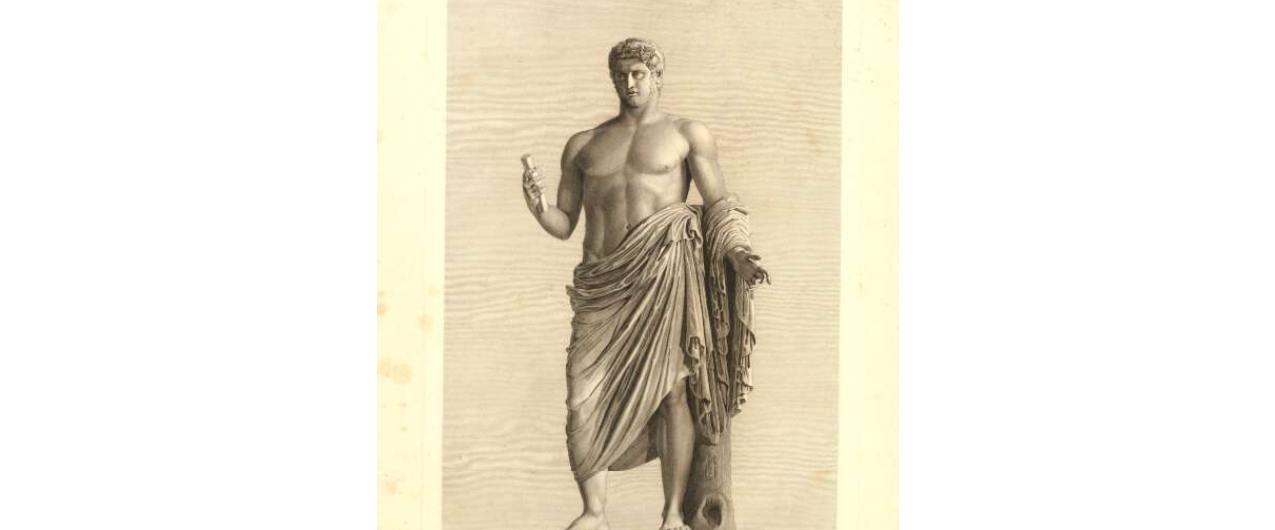

Fig. 4: 1883 Portrait of Oscar Wilde with his Neronian haircut, by Napoleon Sarony.

If Wilde relates the perpetrators of crime with the producers of art in Dorian’s idealised vision of decadent Roman emperors, the idea that crime itself could be an art is arguably best expressed by Thomas De Quincey in his satirical essay ‘On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts’ (1827). Once time has passed, De Quincey declares, or the case had gone cold, we are able to discard any moral considerations tied up with a crime like murder and instead consider the aesthetic properties of different kinds of killing: ‘Fie on those dealers of poison, say I: can they not keep to the honest way of cutting throats, without introducing such abominable innovations from Italy? I consider all these poisoning cases, compared with the legitimate style, as no better than wax-work by the side of sculpture, or a lithographic print by the side of a fine Volpato’.[7] A similar sentiment would be expressed a couple of generations later by Wilde in his own essay ‘Pen, Pencil, and Poison: A Study in Green’ (1889), but using Tiberius and Nero as examples: ‘Nobody with the true historical sense ever dreams of blaming Nero, or scolding Tiberius, or censuring Caesar Borgia. These personages have become like the puppets of a play. They may fill us with terror, or horror, or wonder, but they do not harm us. They are not in immediate relation to us. We have nothing to fear from them. They have passed into the sphere of art and science, and neither art nor science knows anything of moral approval or disapproval’.[8]

De Quincey continues in his essay to explore the idea that those who have an understanding of art’s principles will make better murderers. This does not mean they will necessarily get away with their crime, but rather that they are able to commit murder in a way as to make a lasting, devastating aesthetic impression upon society. His example is of Mrs Ruscombe and her servant in Bristol. De Quincey praises the killer for creating such a gruesome scene that no-one had dared live in the house since for fear of being forced to remember how the scene had looked. The killer was not known to De Quincey, but he marvels: ‘Be the artist, however, who he might, the affair remains a durable moment of his genius; for such as the impression of awe, and the sense of power left behind by the strength of conception manifested in this murder, that no tenant (as I was told in 1810) had been found up to that time in Mrs Ruscombe’s house’.[9] The indivisibility of the artistic from the deviant present in these texts is the same indivisibility which tarnished Nero in the histories and biographies of antiquity. A love of art and theatre made the whole man, the whole emperor, deadly.

The confluence of these decadent themes also makes Nero, somewhat incongruously from a historical perspective, an ideal emperor to embody decline and fall. Although Nero lived some 400 years before the ‘fall’ of the Roman empire in the west, ancient Rome in the nineteenth century imagination was a fluid space, with time periods collapsing into each other. That is how Edward Bulwer-Lytton could figure the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE as the start of decline and fall, and how Wilde could have Nero drape purple cloth over the Flavian colosseum, which was opened 12 years after his death. It is also how Paul Verlaine could invoke two famous Neronians – the emperor’s adviser Seneca and his arbiter of elegance Petronius – alongside the sound of invading enemies in his exposition of the meaning of decadence:

I love the word decadence, all shimmering in purple and gold. … This word suggests the subtle thoughts of ultimate civilisation, a high literary culture, a soul capable of intense pleasures. It throws out the brilliance of flames and the gleam of precious stones. It is made up of carnal spirit and unhappy flesh and of all the violent splendours of the Lower Empire; it conjures up the paint of courtesans, the sports of the circus, the panting of the gladiator, the spring of wild beasts, the collapse among flames of races exhausted by the power of feeling, to the invading sound of enemy trumpets. The decadence is Sardanapalus lighting the fire in the midst of women, it is Seneca declaiming poetry as he opens his veins, it is Petronius masking his agony with flowers.[10]

These moments in history – the reigns of artist-tyrants like Nero or the devastating destruction of cities like Pompeii – work selectively to transform Roman history into a spectacular play, with everyone (courtesans, gladiators, emperors, senators) playing his or her part (much as Nero transformed Rome). By the late-nineteenth century, people were used to seeing Rome on the stage. The ‘sword and sandal’ novel (e.g. Lew Wallace’s Ben Hur [1880] and Henryk Sienkiewicz’s Quo Vadis [1895]) paved the way for the popularity of toga plays in the last decades of the century. Nero’s reign was often a popular subject – the 1896-97 run of Wilson Barret’s play The Sign of the Cross (1896) drew audiences of over 70,000 per week. There were also open-air spectacles, such as Imre Kiralfy’s Nero: Or the Destruction of Rome (first performed in 1889). Once again, in Kiralfy’s title, we see the conflation of Roman periods in history, with Nero bringing about Rome’s fall. But, more importantly, the fin-de-siècle context renewed the tyrannical, criminal Nero’s relationship with the stage. Rome was a familiar setting, one which those settling down in their theatre seats expected to see, and Nero’s reign offered not only the theatricality described in the historical accounts in spades, but also the opportunity to show off the extremes of luxury and decadence that would cause Rome’s demise. No-one in history is better placed to tie together all these themes than Rome’s first actor-emperor.

Notes

[1] Cassius Dio, Roman History 62.6.4-5 in Ernest Cary (trans.) Cassius Dio: Roman History, Vol. 8 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1925), 93-95.

[2] Seneca, Letters 11.7 in Richard M. Gummere (trans.) Seneca: Epistles 1-65 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1917), 63.

[3] Cassius Dio, Roman History 63.9.4-5 in Ernest Cary (trans.) Cassius Dio: Roman History, Vol. 8 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1925), 151-53.

[4] For more on this idea in relation to ancient Roman attitudes to the stage, see Catharine Edwards, The Politics of Immorality in Ancient Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 98-136. For a wider discussion of the trope of antitheatricality across historical periods, see Jonas Barish, The Antitheatrical Prejudice (Berkeley, LA: University of California Press, 1981).

[5] Oscar Wilde, ‘Letter to Robert Sherard’, in Merlin Holland and Rupert Hart-Davis (eds.) The Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde (London: Fourth Estate, 2000), 211.

[6] Oscar Wilde, ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray, the 1890 and 1891 Texts’, in Joseph Bristow (ed.) The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Vol. 3 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 289.

[7] Thomas De Quincey, On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts (London: Penguin Random House, 2015), 39.

[8] Oscar Wilde, ‘Pen, Pencil, and Poison: A Study in Green’, in Josephine M. Guy (ed.) The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Vol. 4 (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 121.

[9] Thomas De Quincey, On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts (London: Penguin Random House, 2015), 38-39.

[10] Paul Verlaine as recounted in Ernest Raynaud, ‘Les Poètes décadents’, La Plume, 2 (1903) 635. Translation after William Gaunt, The Aesthetic Adventure (London: Jonathan Cape, 1945), 119. See also Richard Gilman, Decadence: The Strange Life of an Epithet (London: Secker & Warburg Ltd., 1979), 5-6.