Selling the Sun

Guest post: Professor Melanie Hawthorne

Texas A&M University

Fig. 1: a ‘light show’ over the Seine (with the Conciergerie in silhouette), not far from where Rachilde’s vendor might have been standing. Photo: Melanie Hawthorne.

Despite having spent quite some time thinking about the (many) works of Rachilde (Marguerite Eymery Vallette, 1860-1953), I have never quite known what to make of her one-act play Le vendeur de soleil (The Sun Salesman). It had been published in Théâtre in 1891 (Paris: Savine) but wasn’t performed until June of 1894, when it was staged at the Théâtre de la rive gauche. It concerns a starving artist-type who hits on the idea of making a buck or two by ‘selling the sun’, that is, by standing in front of a setting sun and simply drawing people's attention to it.

My dilemma is this: is he the ultimate con salesman or a cutting-edge conceptual artist? I know some people would say there’s no difference, but I’m not so sure. It may take time for public opinion to catch up with the avant-garde of the art world, but today a banana taped to a wall with duct tape sells for $120,000 (Art Basel Miami Festival), while I'd be lucky to get 50c for the banana on the table in my kitchen, and that, to me, is all the difference in the world. Money talks, and how you convince people to talk about something so that you endow it with huge surplus value is an art form.

So, back to Le vendeur de soleil. On the one hand, Rachilde’s involvement with experimental symbolist theatre in the 1890s suggests that she was attuned not just to the revolutionary developments in theatre, but also to the radical art theories of post-impressionism that were being formulated. People like Paul Gauguin designed programs for some of the performances that included her plays (one was published in Théâtre), and he was one of the ‘Nabis’ artists (such as Edouard Vuillard and Paul Bonnard) who were exploring the idea that painting wasn’t about representing reality at all.[1] It was an exciting moment of fermentation and rapid innovation in the arts, and another example of a how a decadent impulse lights the spark for what will become modernism.

But am I reading too much into the creativity of a desperate salesman? We never learn this protagonist’s name; he is the classic ‘anonymous’, the starving artist who never makes a name for himself. Rachilde refers to him throughout as simply ‘le camelot’. This in itself raises a host of questions. A ‘camelot’ is basically a peddler, an itinerant seller of trifles (also ‘camelot’, or junk), but clearly the origin of the word goes back to the shining castle of Camelot, seat of King Arthur’s legendary court. The word has gone from meaning something desirable to something worthless, designating a pretty bauble that turns out to be all hype (just as Camelot is all myth and no real substance).

The late nineteenth century was the era in which the art of publicity was invented. A perfect storm of capitalist expansion (fueled by developments in transportation and colonial exploitation), increasing rates of literacy, and cheap forms of mass production led to an increase in advertising activity. Some of the most notable and innovative works of graphic art of the fin de siècle were created as advertisement posters (by Henri de Toulouse Lautrec, Alphonse Mucha, Jules Chéret, and others). One of the innovations that both created the need for publicity and benefitted from it was the emergence of the department store in the second half of the nineteenth century, and let us not forget that this was the setting for one of Rachilde’s first works, Monsieur de la Nouveauté (1880).

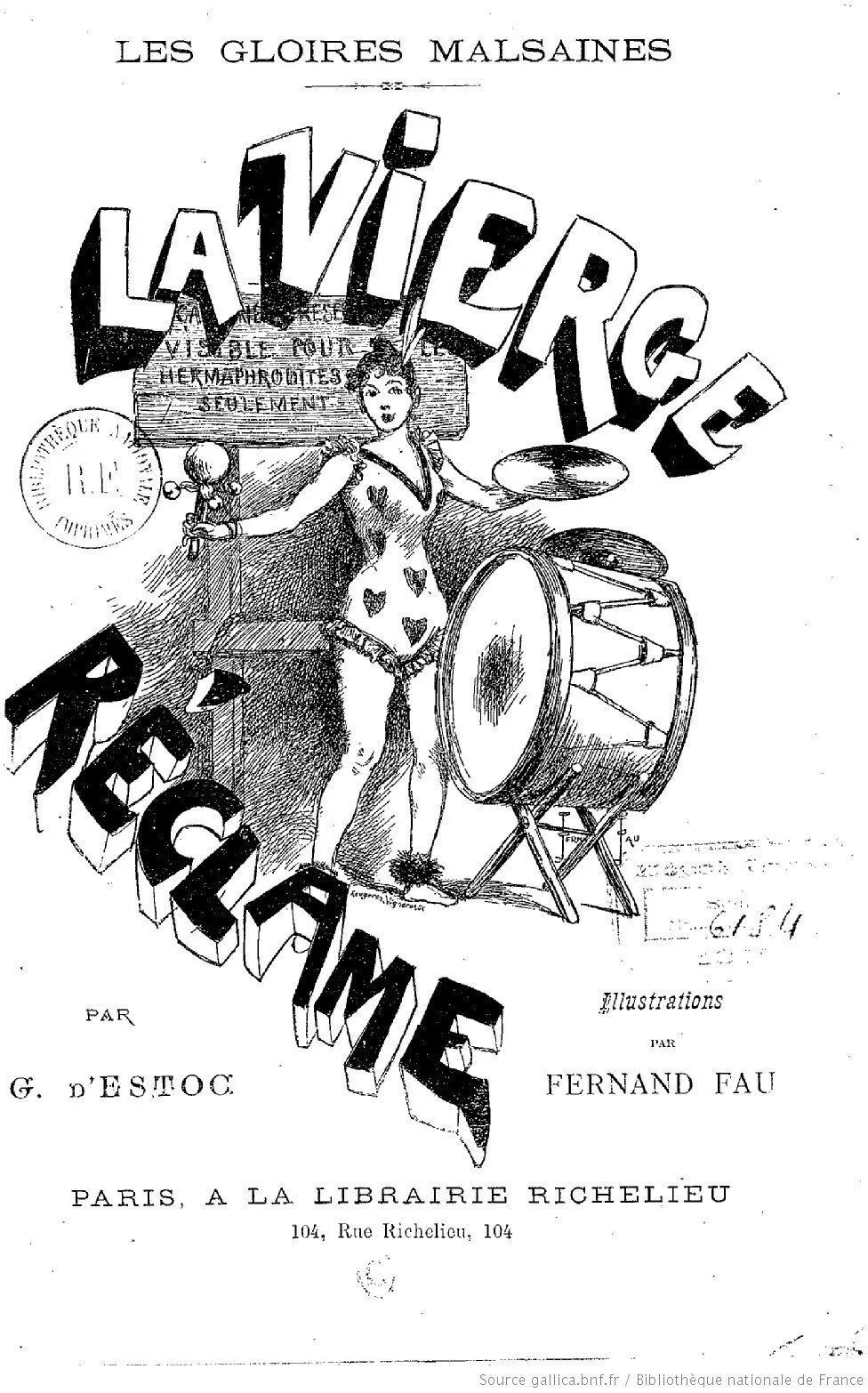

In addition to being attuned to the cultural surge in advertising activity, Rachilde herself was caught up in the wider debates about the merits of it. Was it moral or immoral to exaggerate the properties of a product to generate sales? She herself was accused of using sensationalism to sell her books, with the suggestion being that this was somehow dishonest. A highly critical book by Gisèle d’Estoc (Marie Paule Courbe Parent Desbarres) presented her as a circus barker, drumming up (literally, with a drum) interest in a freak show (her novels often featured characters perceived to be freakish). The cover of the book, La Vierge-réclame, featured a caricatural drawing of this creature. The book referred to Rachilde as, among other things, ‘mengin’ after a notorious street peddler who dressed up in a Roman costume, performed magic tricks, and sold gold-colored pencils that came with an advertising token coin as an added gimmick.

Fig. 2: a drawing by Fernand Fau depicting Rachilde (it is thought, though never specified) drumming up publicity for her novels. Illustration for Les Gloires malsaines: la Vierge réclame, by Gisèle d’Estoc, 1887. Public domain.

So in approaching Le vendeur de soleil, we might suppose that the author’s sympathies are with the protagonist (especially as she claimed to have been a ‘starving artist’ herself in the early days of her career), and that she knows what it is like to be mistaken for a ‘camelot’, when in fact your own perception of your work is that it has serious value.

We get a very long description of the peddler. When the play opens, he is on the pont des Arts in Paris, where he lives, with his back to the setting sun. He is musing on the need to ‘tighten his belt’ out of hunger while waiting for things to get better. We don’t quite know what the ‘things’ are, since the text says only ‘ce sera pour demain’ (that will have to wait for tomorrow), without telling us what ‘ce’ refers to.[2] He is surrounded by people who have plenty of money in their pocket, but are ‘blind’, the kind of people who succeed in life while he starves. He panhandles unsuccessfully, and since he hasn’t eaten in two days, his brain is now as empty as his stomach (295). Leaning over the bridge, he contemplates suicide, but also notices the beautiful sunset that is unfolding on the horizon, ‘un luxe interdit à tous ces crétins-là, qui ne voient rien’ (a luxury denied to all those cretins who don’t see anything, 296). Unsympathetic passers-by tell him to get a job, but he can’t find work; he even offers to carry a bouquet to its destination, but is turned down. He has nothing left to sell, he only has time, but no one needs that (299). He starts to see red, only to realize, once again, that it’s the sunset coloring his field of vision: ‘Oui, c’est le soleil, cette boule jaune, rouge, ces nuages flamboyants’ (yes, it’s the sun, that red, yellow ball, those clouds of flame, 299). The descriptive language hints at what is to come: the peddler may not have ‘goods’ (ironically named) to sell, and no buyers for his time, but he does have one resource to call on: his eye and his powers of description. And that’s how he hits on the solution to his problems: to use his talents as a hawker to help the ‘blind’ passers-by to see what they are missing.

And so he begins his patter, his spiel, listing all the things he isn’t selling, before encouraging the public to step right up and see what he is selling, reassuring them that he isn’t asking for any money (yet), organizing them into spectators (‘Les dames à droite, les hommes à gauche’, ladies to the right, men to the left, 301), hinting at scarcity by citing abundance (‘y en a pour tous .... Y en aura pour les bonnes d'enfant, y en aura pour les militaires!’ (there’s enough for everyone, enough for the children’s nannies, enough for the soldiers, 301)), hyping his product as ‘une marchandise extraordinaire’ (extraordinary merchandise, 302), and keeping up his banter so as to draw a crowd. Drumming up business requires piquing and maintaining the public’s curiosity, which he does through his gift of the gab. Stressing what he is not selling (junk), he describes, verbally, what is in store for the paying customers: he’s not selling writing paper, but ‘l’amour lui-même!’ (love itself), and rather than unbreakable pencils (Mengin again), his product promises ‘des flèches à pointes de flamme qui écrivent en encre grenat plus clairement que dans les livres!’ (darts with points of flame that write in grenadine ink more clearly than in books, 302). Who could resist such a gadget? Who would not want a ‘red ball that will never burst’, let alone ‘le futur, le présent, le passé, la terre et le ciel, le malheur et le bonheur, la pierre philosophale, enfin!’ (the future, the present, the past, the earth and the sky, misfortune and happiness, the philosophers’ stone, in a word, 303)?

Having aroused sufficient interest, he moves to the reveal and the sell, announcing proudly ‘JE VOUS VENDS LE SOLEIL’ (I sell you the sun, 304), and when reactions are mixed (they range from ‘Mais il a raison. C’est épatant’ (he’s right. It’s amazing), to ‘A la porte le fumiste’ (throw the joker out)) he moves on to seal the deal with a long speech, again deploying all his rhetorical talents to convince. The sun is a great beast that he has tamed, it is gold to business men and beauty to women, pink paint to children and ardor to lovers, and so on (305). At the end of the pitch he reminds his audience that there is an expectation of financial remuneration for his performance by generously conceding that for those who don’t want to pay, he will simply give them the sun, and small change begins to rain down at his feet. There is still debate among the spectators as to whether he has earned his reward, but the police, seeing a blockage in the street, move in to disperse the crowd. The peddler is afraid he’ll be arrested, but the police let him collect his earnings, satisfied that the beggar is moving on and no longer disturbing the peace. Looking around at the people staring into the distance, they too look, but can’t see anything. (Rachilde was perhaps thinking of the police who came to see her to discuss one of her novels because they were too stupid to understand it themselves, but expected her to incriminate herself by explaining it to them, an anecdote that became ‘un numéro inconnu’).[3] Maybe they were wrong not to arrest ‘ce pierrot-là’ (that clown), they think (308), the closing words of the play.

And so the play ends without a clear resolution. Was the peddler a con, or a visionary artist who found a way to monetize an experience, one he mediated and created through his own skillful deployment of words and manipulation of context? The sunset is there for anyone to see, but how many of us look, how many of us stop and think about all the things it can represent?

I recall once asking my father if he planned to watch the transit of Venus, a rare event when the planet Venus is visible as a black dot against the background of the sun. It is one of the rarest of astronomical events, and it was going to happen in 2012, and then not again until 2117. I thought for sure he’d want to see it. ‘Why?’ he asked. It might be rare, but it wasn’t so spectacular, he said, whereas the sunset put on an amazing display every night, every night was different. And it was free.

Notes

[1] See Jacques Robichez, Le symbolisme au théâtre: Lugné-Poe et les débuts de L’Oeuvre (Paris: L’Arche, 1957).

[2] Rachilde, Contes et Nouvelles, Suivis du Théâtre (Paris: Mercure de France, 1922), 293. Further references to this edition will be given in the text. All translations are my own.

[3] The ‘souvenir’ was published in Pélagie in 1889. The manuscript is in the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the Univertity of Texas, Austin.