Ellen Terry, Shopping in Byzantium: Decadent costumes fit for a ‘Temple of Art’

Guest post: Dr Veronica Isaac,

University of Brighton

Dame Ellen Terry (1847-1928)

Ellen Terry GBE was one of the leading actresses of her generation. Celebrated across Britain, America and beyond, she ‘charmed’ audiences for over five decades. She achieved this status in spite of a private life which might be considered ‘scandalous’, or, to use terminology more fitting for this article, ‘decadent’ – even today, encompassing two divorces, three husbands, two illegitimate children, and a series of stunning outfits – both on, and off, the stage.

Fig. 1: G. F. Watts, Choosing (1864). Oil on strawboard mounted on Gatorfoam. © National Portrait Gallery.

Her first marriage in 1864 (aged 16) was to the painter George Frederick Watts (1817-1904): a venerated figure, some 30 years older than the teenage Terry. Her last and third marriage – in 1907 – was to an American actor, James Carew (1876-1938), a man 29 years her junior. Carew was also younger than her two children: costumier, director, and political campaigner Edith Craig (1869-1947), and director, designer, and writer Edward Gordon Craig (1872-1966). Both were conceived during Terry’s six-year relationship with artist and designer Edward Godwin (1833-86), with whom she eloped whilst separated from – but still married to – Watts, in 1868. Terry never sought to conceal their illegitimacy, though her marriage to a fellow actor – Charles Wardell (1838-85) – in 1877 may well have been motivated in part by Wardell’s offer to give the children his surname.

Whilst the breakdown of her second marriage was due primarily to Wardell’s alcoholism and violent temper, it was also prompted by her love affair with her stage partner, Sir Henry Irving (then still married, though living separately from his wife, Florence Irving, née O’Callahan, 1843-1934). Terry’s affair with Irving lasted for over a decade and, although fellow performers and close friends were aware of the relationship, it remained a closely guarded secret, not only during their lives, but also for many decades after their deaths. Already condemned by many for being a fallen and immoral woman, Terry was striving to rebuild her reputation and re-fashion her public persona, and her dress played and important part in this re-fashioning. Similarly, even though – as a man – Irving’s sexual indiscretions were judged less harshly, exposure threatened to jeopardise his long held ambition to raise the status of the acting profession, and to establish the actor as a respected artist, as worthy of recognition and honour as famous painters and writers.

Fig. 2: Caricature of Henry Irving and Ellen Terry (1900). Pen and Ink on Paper. © Victoria and Albert Museum.

A Temple of Art?

Terry is arguably most famous for the time she spent as the leading lady of Henry Irving’s Lyceum Company between 1878 and 1902. The success of their twenty-four-year stage partnership – which brought fame and wealth to both – rested on sustaining the Lyceum Theatre’s reputation as a ‘temple of art’ to which leading figures from art and letters flocked to experience the highest standards of stage craft. This was a venue where all spectators (whether in opulent private boxes, or crammed into the gallery) came to be enthralled by ‘pictorial’ dramas which brought spectacular scenes – formally constrained within the frames of two-dimensional canvases – to vivid, three-dimensional life.[1]

As Martin Meisel relates, when Irving invited Terry to join the Lyceum company she ‘brought Irving a great deal more than pictorial appeal, aesthetic credentials, and a following alert to decorative elegance’.[2] Similarly, Henry James (1843-1916), though not an enthusiastic admirer of Terry or her acting, acknowledged that ‘Miss Ellen Terry is “aesthetic”; not only her garments but her features themselves bear the stamp of the new enthusiasm’.[3] Her position as an icon of the Aesthetic movement was cemented by her performances on the Lyceum stage, in particular the 1881 production of Lord Alfred Tennyson’s The Cup. For this production Terry donned costumes which evoked ‘the best of Greek sculptures’ – ‘her picturesque figure robed in stuff that seems spun out of the wings of a dragon fly’. Having received thorough instructions from her former lover, E. W. Godwin, regarding the ‘archaeological’ accuracy of the attitudes she assumed during the performance, Terry succeeded in wearing ‘the Greek costume as if she had been born in it’.[4] The elaborate staging and the classically inspired costumes combined to create a production which was hailed as a ‘banquet of sensuous delicacies’ and a ‘triumph of scenic art’.[5] Indeed the beauty of the production prompted the art critic and self-appointed expert on the Aesthetic Movement – Walter Hamilton – to argue that ‘it is indeed at the Lyceum Theatre that Aestheticism in all its beauty can be seen’.[6]

Fig. 3: Sepia photograph of Ellen Terry as Camma in The Cup at the Lyceum Theatre (1881). © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Terry’s stage career, which began with her appearance alongside Charles Kean (1811-68) in A Winters Tale in 1856, coincided with significant shifts in attitudes towards the design and creation of costume – specifically the increasing importance attached to creating costumes which were ‘archaeologically correct’.[7] As Terry observed in her 1908 autobiography:

Neither when I began nor yet later in my career have I ever played under a management where infinite pains were not given to every detail. I think that far from hampering the acting, a beautiful and congruous background and harmonious costumes, representing accurately the spirit of the time in which the play is supposed to move, ought to help and inspire the actor.[8]

This was certainly true of her time at the Lyceum Theatre where, as Terry soon discovered there was ‘no detail too small for Henry Irving’s notice – He never missed anything that was cumulative – that would contribute to something in the whole effect’.[9] As concerned with the overall ‘picture’ as well as the ‘scenic effects’, Irving ‘would never accept anything that was not theatrically right as well as pictorially beautiful’. To achieve this ‘harmony’, he was prepared to sacrifice the close attention to ‘archaeological detail’ Terry had experienced when performing in the productions Kean collaborated on with the dramatist and antiquary James R. Planché (1796-1880). Initially resistant, Terry soon learnt to appreciate that whilst she ‘knew more of art and archaeology in dress than [Irving] did, he [often] had a finer sense of what was right for the scene’.[10]

Irving was establishing a specific standard and style of performance at the Lyceum. His productions were carefully designed to reaffirm and appeal to the elite status of the aesthetes within his audiences – to reaffirm their expert knowledge and appreciation of art, to pay tribute to their interest in the ‘archaeology’ of dress, and to gratify their desire for lavish ‘pictorial dramas’ which would transport them to the worlds they saw depicted on canvas. Such a theatre offered the ideal platform for an icon of aestheticism – such as Terry – to establish her own decadent style.

Re-Fashioning ‘Decadence’ at the Lyceum

By the late 1880s, the excitement generated by an opening night at the Lyceum theatre stemmed not simply from the calibre of the company’s acting, or the narratives of individual plays; it was also fuelled by the spectacular ‘living pictures’ which had become an integral part of the experience.[11] Given the cultural cachet now attached to attending such productions, and the audience of poets, writers, musicians and artists who assembled within the auditorium, it is perhaps not surprising that the set and costumes presented on the stage often received as much – if not more – attention than the performers. To satisfy the demands of his discerning audience and sustain the Lyceum’s status at the pinnacle of ‘the Drama’, Irving was prepared to invest vast sums in scenery, costume and special effects.[12]

Although Terry was keen to stress that ‘wanton extravagance’ was ‘unknown at the Lyceum’, decadence – as represented in the calibre and quality of design, materials and execution of both set and costume – nonetheless became a tenet of the performances.[13] When interviewed in 1900, Terry’s principal costume maker at the Lyceum, Ada Nettleship, revealed that ‘many of Miss Terry’s dresses have cost £100’. Over £150 was spent on one dress, ‘twilled by [Nettleship’s] girls entirely of gold thread’ for the actress to wear as Guinevere in King Arthur (1895), with the same amount charged for the dress and amber necklace made for Terry as Imogen in Cymbeline (1896)’.[14] In comparison the £47 and £49 that Miss Marie Tempest (1864-1942) had paid for costumes worn in The Greek Slave seem modest. Yet, Terry was not Nettleship’s most profligate customer and her expenditure could be framed as an investment in ‘art.’ By contrast, Miss Winifred Emery (1861-1924) paid £300 for the costumes created for her role in A Marriage of Convenience (where such excessive spending was overtly motivated by the allure and attraction of fashionable display), whilst Miss Brown Potter (1857-1936), who had ‘all her clothes made in Paris’, was widely accepted as the ‘most extravagant stage dresser’.[15]

An insight into the potential ‘decadence’ of spending such huge sums on stage costume can be gathered from a comparison with the sums wealthy shoppers were willing to invest in couture and high quality garments. For instance, the diaries and accounts of Marion Sambourne (1851-1914), a member of the ‘rising middle class’, who had an annual dress allowance of about £80, record that in 1897 she invested £38 in a ‘blue evening dress’ from her favoured designer ‘Madame Bouquet’.[16] Similarly, an analysis of the wardrobe of Heather Firbank (1888-1954), a member of fashionable London society, revealed that whilst in 1909 she spent £1,063 on clothes, she paid £25, 4s for the ‘pink satin evening gown’ she purchased from John Redfern & Sons (a specialist tailor and supplier of couture clothing).[17] Equally, in 1910, an ‘evening dress trimmed with jet and “white diamonds”’ and created by the leading Paris courtier Worth cost 950 francs (approximately £37, 10s).[18] As these examples illustrate, even the ‘legendary prices’ charged for a couture dress from Worth in 1910 are less than half those paid by Terry for a single dress in 1895.

Terry therefore needed to navigate the boundary between extravagance and excess with care. She retained agency over her stage wardrobe, and through close attention to design, materials and construction (and by maximising the potential of whatever budget she had access to) ensured her costumes remained magnificent enough to dazzle, but never ostentatious enough to disconcert, Lyceum audiences.

Fig. 4: Ellen Terry as Guinevere in King Arthur (1895). © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Furthermore, whilst the amount of money and time invested in some of Terry’s most elaborate costumes risked criticism, such extravagance represented a calculated investment in quality, rather than a display of ill-considered and provocative decadence. It was essential that the costumes worn by all members of the cast – and particularly Terry – sustained the high production standards for which the Lyceum Company had gained international renown. To secure ensembles fit for his ‘Temple of Art’, Irving frequently employed famous artists and antiquaries to advise on costume design. He also maintained an in-house wardrobe and, where the production, performance, or in Terry’s case – the performer – demanded, he was willing to pay expert costumiers and dressmakers to produce elaborate costumes, which would continue to impress and enchant audiences.

A fitting wardrobe for ‘The Leading Lady of the Lyceum’

Terry’s position as the leading lady of Irving’s company granted her an unusual degree of control over the costumes in which she appeared on stage. Highly attuned to the communicative power of clothing, Terry employed her stage wardrobe as a vehicle through which to demonstrate her understanding of ‘colours, clothes and lighting’, and to showcase her ‘sense of decorative effect’.[19] Terry had gained this knowledge during her relationships with artists such as Watts and Godwin. She refined her skill and technique further through her collaboration with the costume designer Alice Comyns-Carr, and dressmaker Ada Nettleship (1856-1932). Like Terry, Comyns-Carr was an enthusiastic advocate of Aesthetic dress, whilst Nettleship had created the pale yellow gown worn by Constance Lloyd (1858-98) for her wedding to Oscar Wilde in May 1884. Together the three women became known for the ‘beautiful and artistic’ costumes they created for Lyceum productions and worked together between 1887 (when Comyns-Carr was first appointed as Terry primary costume designer) until 1902 (when Terry left the Lyceum Company).[20]

What sets Terry apart from other performers during this period, was her recognition – and deliberate exploitation – of the communicative power of dress. The garments she chose to wear, both on and off the stage, played an integral part in a wider process of self-fashioning through which she manipulated the persona presented to her audience. As Catherine Spooner has argued, decadent fashion was founded upon ‘an embodied knowledge of style’.[21] Terry embraced this approach to dressing, but elevated it. To borrow from Spooner’s phraseology, Terry’s personal style represented ‘an embodied knowledge of art’. It was a style she refined during, and following, her time at the Lyceum, and there was a noticeable shift in the boldness within which she embraced her identity as a figurehead of aestheticism, following Comyns-Carr’s elevation to her chief costume designer. Terry continued to discuss designs with the scene painters, consulting them ‘about the colour, so that [she] should not look wrong in their scenes, nor their scenes wrong with my dresses’.[22] From 1887 onwards, however, she gained the confidence to adopt costumes which, though harmonising with her backdrop, stood apart from the garments worn by other performers and which aligned more directly with her personal taste and artistic principles. These were garments which consciously invited the audience to notice – and gain an increased respect for – both their wearer, and her performances.

As Sarah Parker has established, ‘women’s participation in Decadence is difficult to categorise’ and, like the ‘women writers’ Parker examines, Terry ‘found in Decadence ways to utilise and transform Decadent imagery towards [her] own ends.’ Terry’s rebellion was achieved through clothes – rather than words – and was arguably more subtle. Yet, as Spooner observes, ‘Decadent fashion stylings […] produce an active engagement with aesthetics that enable intervention into systems of power, privilege, and beauty’. Furthermore, as Terry’s manipulation of her costumes demonstrates – in expert hands – ‘[f]ar from an evacuation of moral responsibility, the decadence of fashion may be a means of astute political commentary’.[23] Understanding the ‘art’ and power of dress, Terry embraced her reputation for femininity and artistic dress, transforming qualities generally seen as a visual manifestation of submissive conformity into the source of her agency. For Terry, a woman’s ‘seductive’ power (feminine charm) offered a means through which to subvert decadent dismissals of woman as ‘inartistic’ – a way to challenge the idea that women are solely ‘decorative’, and the female body represents ‘“raw material” that needs to be shaped into art’.[24] Working with two other women to create her theatre costumes, and overseeing the design and creation of the garments she wore on and off the stage, Terry remained willing to ‘embody art’, but retained control over the ‘art’ she embodied.

Fig. 5: Photograph of Ellen Terry as Ellaline in The Amber Heart (1887). © Victoria and Albert Museum.

‘Ellen Terry’s’ Lady Macbeth (1888-89)

In spite of the controversial nature of her private life, Terry’s celebrity was founded, at least in part, on her position as ‘an icon of traditional feminine tenderness and virtue’.[25] The frustration Terry felt regarding this characterisation, and the restrictions it placed on her professional ambitions, are apparent in her private and published writings – specifically her declaration that critics were too ready to ‘[g]ive a dog a bad name and hang him – the bad name in my case being “a womanly woman”!’[26]

The announcement that she was to play Shakespeare’s ambitious murderess, Lady Macbeth, therefore provoked immediate controversy. Many felt that Terry’s ‘gentle womanliness’ would make it ‘impossible to for her to utter convincingly such a speech as that hideous invocation to “thick night” and the Spirits of Evil’, and that representing Lady Macbeth’s ‘diabolical and fiendish’ qualities was ‘beyond the wide scope of Miss Terry’s genius, great as it unquestionably is’.[27] Frustrated by such limiting and condescending predications, Terry remained determined to present her own, carefully researched, interpretation of Lady Macbeth – a portrayal which acknowledged, but rejected, actress Sarah Siddons’s (1775-1831) definitive performance of the role. Above all, she sought to challenge Siddons’s assertion that Lady Macbeth represented a ‘woman in whose bosom the passion of ambition has almost obliterated the characteristics of human nature’.[28] Instead, Terry wanted to show that Lady Macbeth was ‘[a] woman (all over a woman)’ who ‘was not a fiend, and did love her husband’.[29]

Costume played a crucial role in supporting her performance, providing an immediate statement of her reading of the character. This is particularly evident in the dress she wore for her entrance (Act 1, Scene 5) and in the Banquet scene (Act 3, Scene 4). The fame of this first costume has been secured by the portrait John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) created of Terry wearing the ‘Beetle-wing’ dress in 1888. Sargent was amongst the spectators present at the opening night of the production. Indeed, Comyns-Carr claimed that it was witnessing Terry’s striking entrance, together with the moment in the next scene when she re-appeared with a heather velvet cloak embroidered with fiery griffins, and swept out of the castle keep to greet the old King, that inspired Sargent to create the portrait.[30] The portrait – which shows Terry with arms upraised, a crown held above her head – conveyed elements of the costume missing from the photographs which, as Terry stated in a letter to her daughter, ‘give no idea of it at all, for it is in colour that it is so splendid’.[31] It captures a costume which had been deliberately designed to reproduce the effect of ‘chain mail’, an impression heightened by the serpentine gleam of the blue green beetle wing cases and metal tinsel which covered its surface.[32]

Fig. 6: John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth (1889). Oil on canvas 1889. © Tate Britain.

The ‘Beetle-wing dress’ was arguably one of the most ‘decadent’ costumes created for Terry to wear on-stage. The silhouette of the dress evoked gowns from the early medieval period (1100–1300) that were deemed appropriate for the setting for the play.[33] Having ‘cut out the patterns [for the dress] from the diagrams in the wonderful costume book of Viollet le Duc’, Nettleship (together with her team of makers) then crocheted a fine yarn formed from ‘a twist of soft green silk and blue tinsel’, sourced from Bohemia, ‘to match them’.[34] As both Comyns-Carr and Terry would have been aware, the glittering strands of metal thread running through this crochet glowed eerily in ‘thick softness of gaslight with the lovely specks and motes in it’.[35]

However, Comyns-Carr was concerned that the dress might not be ‘brilliant enough’. Contemporary fashions, specifically the beetle-wing cases used to embellish elegant evening wear, provided the solution, and thousands of these shimmering wing cases were hand-sewn across the surface of the dress.[36] This, together with the further addition of ‘a narrow border in Celtic designs, worked out in rubies and diamonds’ at the hem and sleeve cuffs, completed the costume.[37] When fully dressed for the role, a wide metal belt encircled Terry’s waist, a veil (held in place by a circlet of ‘rubies’) covered her head, and two long auburn plaits twisted with gold hung to her knees. The ensemble also included ‘a cloak of shot velvet in heather tones, upon which great griffins were embroidered in flame coloured tinsel’.[38]

The full ensemble – with its glittering gown, flame-coloured hair and swirling cloak – provided Terry with a form of ‘armour’ that conveyed her Lady Macbeth’s majesty and power, and yet retained sufficient signs of femininity and beauty to placate even the harshest of critics.

Fig. 7: Photograph of Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth in Macbeth, Act 1, Scene 5 ( 1888). © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Whilst her fellow performers – including her co-star Henry Irving – wore far more subdued costumes in earthy tones of deep purple and brown, Terry’s costumes remained spectacular and deliberately set her apart. Though critics were generally willing to forgive this discrepancy, it did not pass unremarked. Oscar Wilde observed: whilst ‘Lady Macbeth seems to be an economical housekeeper and evidently patronises local industries for her husband’s clothes and servant's liveries […], she takes care to do all her own shopping in Byzantium’.[39]

The ‘regal robes’ Terry donned to mark her accession to Queen in the Banquet Scene (Act 3, Scene 4), whilst not as famous as the beetle-wing dress, were equally lavish. This gown, worn with a sumptuous golden cloak, had the same hanging sleeves and trailing skirt as Terry’s previous dress, but the gleaming green/blue was exchanged for glittering gold. Embellished with cut-glass jewels, and with strips of gold thread running through the cream fabric and coiling into swirling patterns at the centre front of the bodice, this costume was described by one reviewer as ‘the crowning achievement. Beside [which] Sarah Bernhardt’s Byzantine stole pales in ineffectual splendour’.[40] Like the costume created for King Arthur in 1895, this regal gown is likely to have cost well in excess of £100. The gold thread which covers the bodice and runs through the fabric contains actual gold – it is formed from an orange silk core bound in thin strands of gold which were first beaten flat and applied to a paper backing. These threads would have to be created by hand and were probably imported from Japan where it was (and is) used as embroidery thread. Enhanced by Irving’s carefully controlled stage lighting, the brilliant glow of these golden strands would have commanded the audience’s admiration and attention, permitting Lady Macbeth a brief moment to relish her majestic triumph before her fatal destiny intervened.

Fig. 8: Photograph of Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth in Macbeth, Act 3, Scene 4, Lyceum Theatre (1888). © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Fig. 9: Detail of the surviving costume, now part of the Ellen Terry Collection and held by the National Trust. © Personal image by the author.

Only when struck by the tormenting guilt, which would ultimately destroy both her mind and body, did Terry’s Lady Macbeth exchange her splendid gowns for a plain white nightdress. In Lady Macbeth’s final moments, both this crumpled and austere ‘undress’, together with her now dishevelled auburn hair, signalled that this was a woman succumbing to moral and mortal decay, which threatens to consume all who stray too far in their pursuit of decadence.

Fig. 10: Photograph of Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth in Macbeth, Act 5, Scene 1, Lyceum Theatre (1888). © Victoria and Albert Museum.

A Decadent (but subtle) Subversion

This was not the only production in which Terry had, or would, experiment with values and iconography which might be termed ‘decadent’. However, in contrast to her whole-hearted embrace of aestheticism, Terry remained firmly – and deliberately – on the edges of a decadent sensibility. Perhaps the ‘true’ significance of Terry’s engagement with decadence lies in when and how she chose to engage with the movement, and the behaviour decadence licensed?

Terry’s aspirations to respectability rested on sustaining and characterising her professional identity as that of a loving mother who worked out of necessity, and whose success stemmed from hard work and a desire to be ‘useful’, rather than any personal ambition.[41] Any departure from this ‘character’ – whether on stage or in private – risked undermining this carefully constructed persona. Yet Terry was clearly frustrated by the critics who declared that her acting talents rested on her ‘charm’ and feminine grace, or who suggested her limited abilities were only suited to submissive tragic heroines, or comic roles (in which any initial intractability or independence was ultimately subsumed by romance/marriage).[42] Cultivating a decadent style on and off the stage provided Terry with both the artistic medium and opportunity to exploit and subvert the ‘grace’, ‘charm’ and ‘womanliess’ for which she was so often praised.

The 1888 production of Macbeth represented the first in a series of carefully calculated and contained sartorial rebellions in which she challenged such critics. Clothed in the crocheted chainmail of a murderous monarch (Lady Macbeth, 1888), Terry was able to resist the constraints her characterisation as a ‘womanly woman’ placed on her professional career.

Seeking a medium of self-expression which aligned with feminine ideals of the period, Terry recognised that dress offered a socially-acceptable route towards gaining agency over her public and private identity. For Terry ‘decadent fashion stylings’ provided both a vehicle through which to subvert her professional persona, together with a defiant visual statement that there was ‘more to [her] acting than charm’.[43]

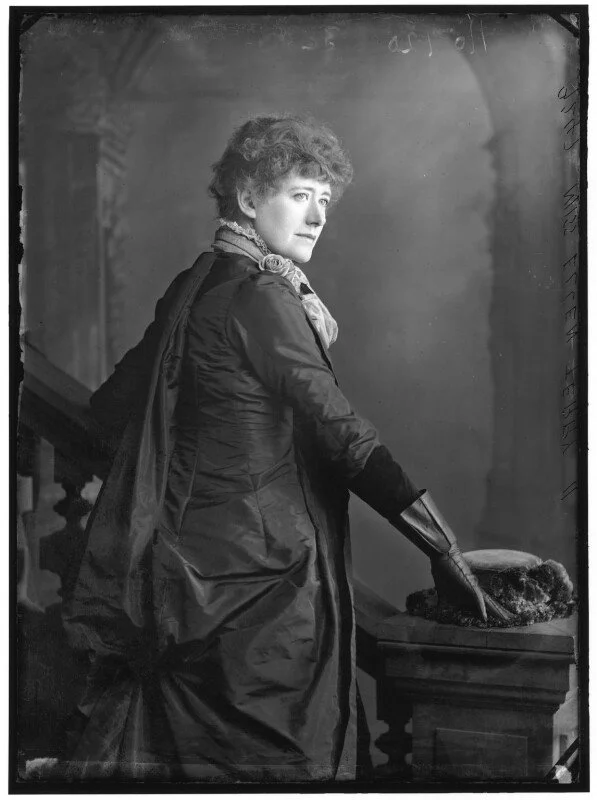

Fig. 11: Alexander Bassano. Ellen Terry (1880). © National Portrait Gallery.

Notes

[1] Martin Meisel, Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial, and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1983), p. 403.

[2] Meisel, Realizations, p. 403.

[3] Henry James, The Nation, 13th June 1879 (J.H.Richards: New York)

[4] Catherine Arbuthnott, Edward William Godwin, and Susan Weber. E.W. Godwin: Aesthetic movement Architect and Designer (New York: Bard Graduate Centre, 1996) p. 35; “The Cup,” Truth, Jan 13th 1881, p. 47. Press Cutting, Percy Fitzgerald Album, Vol IV: pp. 175-6. Garrick Club, London; Illustrated London News, 5 Feb 1881, p. 124. Press Clipping in file MM/REF/TH/LO/LYC/21. University of Bristol Theatre Collection.

[5] The Daily Telegraph, 4 January, 1881. Press cutting, Percy Fitzgerald Album, Volume I: pp. 141-43, Garrick Collection, London; G.A.S. The Illustrated London news, 8 Jan 1881, p. 31. Press Cutting, Production file for ‘The Cup’, Lyceum Theatre, 1881. Department of Theatre and Performance, Victoria & Albert Museum.

[6] Walter Hamilton, The Aesthetic Movement in England (London: Reeves and Turner, 1882), pp. 31-32.

[7] Oscar Wilde, ‘Truth and Masks’, Intentions. The Decay of Lying; Pen, Pencil, and Poison; The Critic As Artist; The Truth of Masks (London: Osgood, 1891) [Online edition, Project Gutenburg, Transcribed from the 8th edition published by Methuen and Co. in 1913], n.p.

[8] Ellen Terry, The Story of My Life (London: Hutchinson, 1908), p. 10.

[9] Terry, The Story of My Life, p. 170.

[10] Terry, The Story of My Life, pp. 108 and 157.

[11] Meisel, Realisations, pp. 402-05.

[12] Jeffrey Richards, Sir Henry Irving: A Victorian Actor and His World (London: Hambledon and London, 2005), p. 5.

[13] Terry, The Story of My Life, p. 171.

[14] ‘What Actresses Pay for their Dresses’. New Zealand Herald, 25 August 1900, p.2.

[15] New Zealand Herald, 25 August 1900, p. 2.

[16] Amy de la Haye, Lou Taylor and Eleanor Thompson, A Family of Fashion, The Messels: Six Generations of Dress (London: Philip Wilson Publishers, 2005), p. 37.

[17] As the authors note, Firbank generally received an annual clothing allowance of £525. They also record that although initially specialising in tailoring Redfern had by this point expanded into all fashionable clothing including court dress. Cassie Davies-Strodder, Jenny Lister, and Lou Taylor, London Society Fashion 1905-1925: The Wardrobe of Heather Firbank (London: V & A Publishing, 2015) pp. 39, 111, and 142.

[18] This sum is quoted in a letter from a private collection and is cited in Davies-Strodder, Lister, and Taylor, London Society Fashion 1905-1925, p. 114.

[19] Terry, The Story of My Life, p. 150.

[20] ‘Ellen Terry’s Gowns and the Woman who makes them.’ The Queenslander, 3 April 1897, p.747.

[21] Catherine Spooner, ‘Fashion: Decadent Stylings’, in Jane Desmarais and David Weir (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Decadence (Oxford: Oxford University Press). E-book available online: https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/35426.

[22] Terry, The Story of My Life, p. 169

[23] Spooner, ‘Fashion’.

[24] Sarah Parker. ‘The New Woman and Decadent Gender Politics’. Decadence: A Literary History Ed. Alex Murray (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020) pp. 118-135, 120

[25] Sos Eltis, Acts of Desire: Women and Sex on Stage, 1800-1930 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 179.

[26] Terry, The Story of My Life, pp. 328-29.

[27] ‘The Real Macbeth’, Unidentified periodical, ca. December 1888, Press Cutting, mounted in Percy Fitzgerald Albums, Volume V: p. 311, Garrick Collection, London.

[28] Siddons’ ‘Remarks’ were published by Thomas Campbell in his Life of Mrs. Siddons in 1834. A first edition of Thomas Campbell’s text forms part of the library at Smallhythe place. Siddons’ Remarks on the Character of Lady Macbeth appear in Volume 2 of the two-volume work by Campbell, Life of Mrs. Siddons, Vol. 2 (London: Effingham Wilson, 1834), pp. 10-34.

[29] Terry, The Story of My Life, p. 307. See also the handwritten annotation on her copy of Joseph Comyns-Carr’s Macbeth and Lady Macbeth: An Essay, p. 28.

[30] Alice Comyns-Carr, Mrs. J. Comyns-Carr's Reminiscences (London: Hutchinson, 1926), pp. 299-300.

[31] Terry, The Story of My Life, pp. 293-4.

[32] Comyns-Carr, Mrs. J. Comyns-Carr's Reminiscences, pp. 211-12.

[33] Emma Slocombe, ‘Lady Macbeth at the Lyceum’, National Trust Historic Houses and Collections Annual 2011 (London: National Trust, in association with Apollo, 2011), p. 10.

[34] Alice Comyns-Carr, Mrs. J. Comyns-Carr's Reminiscences (London: Hutchinson, 1926), pp. 211-12.

[35] Gaslight was still used in the Lyceum Company productions, even after electric lights were developed for the stage and installed in many theatres. Terry, Story of My Life, p. 173.

[36] Valerie Cummings, ‘Macbeth at the Lyceum’, Costume 12 (1978), p. 58.

[37] Comyns-Carr, Reminiscences, pp. 211-12.

[38] Comyns-Carr, Reminiscences, pp. 212-13.

[39] Wilde’s statement was recalled and quoted by W.G. Robertson, Time Was: The Reminiscences of W. Graham Robertson (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1931) p. 151.

[40] Pall Mall Gazette, 31 December 1888, p. 4. Percy Fitzgerald Album, Volume V: p. 330, Garrick Club, London.

[41] This was a claim Terry repeated frequently both in public interviews and private marginalia. See, for instance Terry, The Story of My Life, p. 41.

[42] Her frustration is apparent in letters of the period. It also prompted her to include a satirical sketch entitled ‘What Constitutes Charm: An Illustrated Interview with Miss Ellen Terry’ in her 1908 autobiography. In this sketch Terry’s charm provides an excuse to behave in an increasingly rude manner, donning a false nose, throwing a nearby child out of a window and – ultimately – despatching her interview out of the door with a ‘vigorous kick’. Terry, The Story of My Life, pp. 265-68.

[43] Ellen Terry, Four Lectures on Shakespeare, edited and with an introduction by C. St John (London: Martin Hopkinson Ltd, 1932), p. 13.