Leigh Bowery: Glitter, Shit, and the Performance of Decadence

Guest post: Dr Sofia Vranou (Queen Mary, University of London)

‘Too much of a good thing can be wonderful!’[1]

― Mae West

Fig. 1: Leigh Bowery, 1988. Photo by Werner Pawlok.

1986: Taboo club, London. No amount of distress or discomfort limited Leigh Bowery’s artistic vision. By manipulating his appearance drastically with sculptural claustrophobic outfits, strange headpieces, layers of make-up, and dangerously high platform shoes that made him into a towering figure more than seven feet high, Bowery came to exemplify the subtle art of going out. He moved to London from his native Australia only a few years earlier, in 1980, bringing with him a portable sewing machine in the hope of becoming a fashion designer, but being at odds with mainstream trends and normative ideals of beauty soon distanced him from his initial plans. The bizarre and extravagant outfits Bowery designed and regularly showed off in nightclubs and the street eventually turned him into a subcultural icon, a postmodern dandy of sorts with a highly distinctive and unprecedented practice of creative self-fashioning. The council flat he shared with friends in East London was equally bizarre and deliberately garish. UV lights, tacky wallpapers, black tiled floors, plenty of mirrors, and a clashing combination of textures and patterns constructed a well-calculated visual cacophony that served, Bowery stated, as ‘an extension’ of his unique fashion sense.[2] He started to get noticed as an emerging fashion designer by making clothes for his scenester friends (including Boy George), and achieved significant connections and exposure with fashion shows in the UK and internationally. However, Bowery disliked the thought of mass-producing his garments and potentially having to compromise to satisfy the commercial demands of the fashion industry. What he craved instead was to have all the spotlights on himself as he paraded his imaginative looks in London’s trendy nightclubs. Devoting himself to performance, therefore, seemed like a natural and inevitable progression.

Fig. 2: Leigh Bowery and Trojan in their flat in Farrell House, 1984. Photo by Steve Pyke.

Bowery performed in prestigious theatres in the UK and abroad during his short and multifarious artistic journey, most notably with Michael Clark’s dance company (1986-92), for which he also designed costumes. Furthermore, he had the chance to present a solo living installation at the reputable Anthony d’Offay Gallery (1988) and a collaborative performance (with Mr. Pearl and Nicola Bateman) at the Serpentine Gallery (1989), both in London. Yet, Bowery found such conventional venues ‘slightly limiting’ in comparison to the freedom and spontaneity that typified the sweaty nightclubs he frequented and commonly performed at.[3] It was the decadent – to the conservative gaze – vibe of seedy nightclubs, speaking perhaps to Bowery’s own desire for what is ordinarily considered distasteful or vulgar, which fuelled his excitement and underpinned his intoxicated impromptu performances and improvisations in spectacularly queer outfits that blurred the boundaries between fashion, art, and life. Heaven, Torture Garden, Camden Palace, and Kinky Gerlinky in London, and Limelight in New York, are just a few of the most remarkable nightclubs of that period that Bowery performed at before dying abruptly from an AIDS-related illness in 1994.

Fig. 3: Flyer (front and back) for a performance of Leigh Bowery with Minty at Torture Garden, 1994. Courtesy of the Leigh Bowery Estate.

Through his flamboyant presentation of self and outrageous demeanour, Bowery encapsulates the postmodern embodiment of decadence. What was once synonymous with nineteenth-century modern dandies like Oscar Wilde and the shameless celebration of opulence and excess was epically remodelled during the 1980s by Bowery’s wild aesthetics and attitude. And while decadence has acquired throughout the years positive and negative associations, Bowery’s paradigm playfully embraces both. Not only did Bowery lead an extraordinary life of aesthetic hyperbole, unrestrained pleasure, and narcissism, but as a queer artist on the margins he also often explored decay and moral ‘sickness’ in his performances as a strategy of survival against the repressive normative conventions and burgeoning conservatism of his era. Soaked in glittery indulgence, artificiality, and transgression, his decadent embodiment needs to be understood in conjunction with a turbulent sociopolitical period in the UK defined by extreme contradictions: from the rise of greedy consumerism, shoulder pads, and a generation of yuppies, to the political decline and austerity marked by neoliberal Thatcherism and the explosion of the global health crisis of HIV/AIDS. His club night Taboo, a playground for sparkle and uninhibited hedonism, and a memorable performance at Fridge club for an AIDS benefit cabaret, during which he sprayed the audience with an enema, constitute two contrasting sides of Bowery’s performed decadence. Drenched in glamour or shit, Bowery proved a marvellous contemporary decadent.

Taboo and Glory

In 1985 Bowery and entrepreneur Tony Gordon inaugurated their legendary club night Taboo which was held weekly at Maximus, a small basement disco in Leicester Square. Taboo adopted a strict door policy as emphasis was placed on exquisite appearances, and the catchphrase ‘Dress as though your life depends on it’ became its motto, encouraging deep experimentation with style and subjectivity and promoting a strong sense of theatricality. The club night favoured an anything-goes mentality and an anarchic approach to music and dress. The interior décor, Bowery’s close friend Sue Tilley recalls, was ‘extremely and perfectly tacky’ with ‘[t]atty red velour banquettes, mirrors everywhere, strange light effects on the walls, three bars and a central dance floor with several cheap lights and a mirror ball’.[4] The music clip of trans artist Lana Pellay’s Hi-NRG hit Pistol in My Pocket (1986) was filmed on the premises, and provides a glimpse of the flashy interior (which couldn’t be more fitting for the mischievous lyrics ‘I got a pistol in my pocket, baby. I got it pointed at you’), and features some of the habitués of Taboo including Bowery. The latter is shown in full masquerade and clownish make up welcoming the camera/viewer to a frenzied party before mixing with the colourful dancing crowd that surrounds Pellay, who performs on a platform.

Vid. 1: Lana Pellay, Pistol in My Pocket (1986).

In his thorough account of modern British nightclubbing, Dave Haslam remarks humorously that attendants at Taboo ‘didn’t just wear mad outfits; they became new people’, and goes on to assert that ‘Bowery replaced the […] mainstream version of “gender-bending” with something more hardcore and outsider’.[5] Being the public face of Taboo, a role that inevitably entailed being in the spotlight, demanded that Bowery re-invent himself stylistically each week. His desire to show off and attract attention led him to push the boundaries and surpass himself constantly, approaching costuming as a form of contemporary art rather than simply an imaginative fashion mélange. His crafted outfits, which in later years were produced with the help of his assistants and close friends Nicola Bateman and Lee Benjamin, became increasingly more complex and avant-garde during his Taboo days. It was also around the same period when Bowery decided to shave all his hair off and use his head as a canvas by applying splashes of coloured PVA glue (the pigment of which varied according to the outfit) that dripped evenly to the sides of his heavily made-up face.

Fig. 4: Trojan, Nicola Bateman, and Leigh Bowery at Taboo, 1985. Photo by Dave Swindells.

Soon Taboo caught the attention of i-D, a seminal style magazine invested at the time in scrutinizing and recording emerging subcultural street fashions and club scenes. With stories praising the club’s polysexual character, endorsed by Bowery’s phenomenal queer embodiments, Taboo came to be London’s most debauched club, leaving a distinctive mark in the history of clubbing and the cultural politics of queer visibility. The publicity not only contributed to the success of Taboo as ‘the pinnacle of deranged, decadent expression’, as Richard Torry puts it; it also established Bowery as the quirkiest figure of London’s subcultural club scene in the mid-1980s.[6] A year after opening its doors, Taboo’s hedonistic ambience reached You magazine, a publication distributed for free with the conservative tabloid Mail on Sunday. The article made explicit allegations of extensive drug use, alcohol abuse, and supposedly indecent behaviour taking place on the premises. As a result, the management of the venue decided to suspend the club night. When the fuss subsided a few weeks later and Bowery was approached to resume Taboo he declined. As a result, its reputation and legacy as ‘London’s sleaziest, campest and bitchiest club’ was preserved intact before turning into a corny attraction to outsiders due to mainstream media attention.[7] With its tawdry disco dancefloor turning into Bowery’s stage, Taboo was a milestone in his art and life, and a convenient stimulus, perhaps, for permanently shifting his focus from fashion design to art and performance. Although he never abandoned clubbing, Bowery moved from his role as a regular club host to more specific performance-related activities involving extravagant costuming and a plethora of collaborations with various creatives.

During a troubled time of deep recession and hopelessness, Taboo can be viewed, Thomas Mießgang characteristically writes, as ‘the apotheosis of a flamboyant life plan which in its excess, visual exuberance and provocation aimed to formulate an alternative to the philistine ruthlessness of neoliberalism, whose visual metaphor could be found in the rigid hairstyle of Margaret Thatcher’.[8] Serving as a queer hub, Taboo allowed dress-up fantasies, freedom of expression, and experimentation with gender identity to be gallantly (and safely) performed amid a decade that was deeply affected by severe austerity measures and the threat of a ‘gay plague’: the casually homophobic label given initially to AIDS, for it was erroneously believed it could only spread among promiscuous male homosexuals. As such, Bowery’s queer self-fashioning, narcissism, and unapologetic hedonism acquire significant radical potential. They turn into bold political statements of queer visibility and cultural interventions that resist the heightened political depression and lurking homophobia that had intensified by the AIDS crisis. His bold egocentrism echoes Charles Baudelaire’s famous interpretation of dandyism as ‘the last spark of heroism amid decadence’, which clearly marks the figure of the dandy as someone who seeks to disrupt decline and evade an impending catastrophe.[9] Sadly, Bowery was one of the millions who eventually succumbed to AIDS complications, but his flamboyant life remained triumphant and resplendent until the end.

AIDS and Decadence

Bowery kept his HIV-positive status a sealed secret even from his closest friends (apart from Tilley), and he never explicitly addressed it through his work. His determination to keep his diagnosis private stemmed from his anxiety to be remembered as a creative person with vision and not as someone who had AIDS. This assumption that coming out as HIV-positive would overshadow his artistic legacy is very likely conditioned by the frenzied reaction and moral panic the global epidemic generated through the regular sensationalist stories and negative representations of people with AIDS in the media. With over 2.5 million confirmed cases of HIV/AIDS by the early 1990s worldwide and coming to terms with the fact that anyone without exception could potentially be exposed to the virus – and not just gay men, sex workers, and IV-drug users, as it was initially believed – the media on both sides of the Atlantic took on a shared mission of raising awareness among the ‘respectable’ general public (which they considered exclusively heterosexual), often misinforming it to satisfy their moralistic agenda. This strategy in combination with shocking images of emaciated people dying from AIDS complications and the extreme measures proposed by certain conservative representatives (such as quarantining, tattooing, and even sterilising HIV-positive persons) fuelled the demonisation of gay men as depraved, reckless, and promiscuous, and led to the irrational stigmatisation, victimisation, and shaming of those living with the virus.[10]

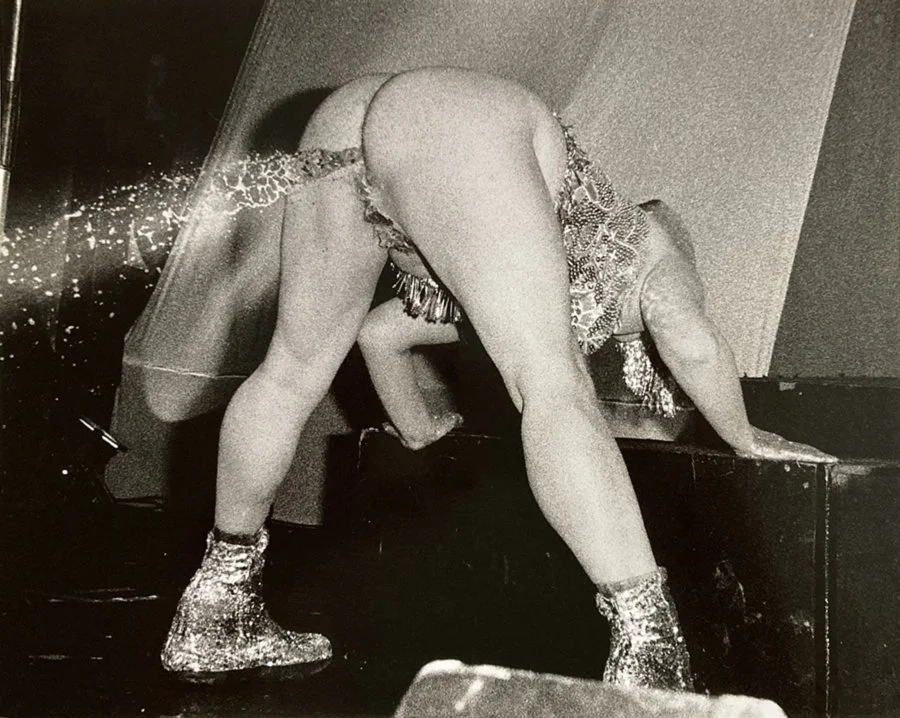

Perhaps the only time Bowery was involved in any kind of politically charged venture was when he reluctantly agreed to perform at Heart’s in the Right Place, an AIDS benefit cabaret at the Fridge in Brixton on Valentine’s Day in 1990. Distanced from AIDS activism, which he unfairly believed sustained a general feeling of victimhood, Bowery ceaselessly rehearsed a dance routine that involved squirting a water fountain from his bare ass using an enema: a spectacle that didn’t quite go as expected. His attire for the performance included a beaded corset that squeezed his chubby flesh creating a rich bosom, an elaborate headdress, glittery ankle boots, and what he called a ‘merkin’: the crown of an old wig glued onto his taped-back penis to give the illusion of a female crotch. To make an entrance Bowery climbed on the shoulders of a friend – the film director Baillie Walsh – and put on a very long cloak that covered both, conveying the illusion of a queer, towering creature. After taking the stage Bowery clambered off Walsh’s back, removed the cloak, and danced around clumsily for a while until it was time for the highlight of the now-legendary performance. He bent down protruding his ass towards the unsuspecting spectators below and, according to Tilley’s graphic account, ‘a nasty stinking brown mess spurted out of his bottom’ (which she puts down to his awfully tight corset) landing on the audience at the front ‘who were all sitting at beautifully decorated round tables’, creating havoc.[11] Without losing focus, Bowery climbed back on Walsh’s shoulders, who had to endure the stench of the disgusting mess smeared all over him. The scandalous performance was considered by some to be ‘particularly tasteless’ and offensive for an AIDS benefit, and it also infuriated Lambeth Council, which tried to close the club down.[12]

Bowery defended himself by stating:

If you’ve got AIDS it doesn’t mean you’ve lost your sense of humour, does it? I didn’t want to make concessions just because people were ill or dying. I was quite pleased with the hostile reaction. If anything I want to make reactions stronger. If I have to ask, ‘Is this idea too sick?’ I know I’m on the right track.[13]

Fig. 5: Leigh Bowery performing at the Heart’s in the Right Place AIDS benefit at Fridge, 1990. Photo by Gordon Rainsford. Courtesy of the Bishopsgate Institute.

Sickness as a ‘metaphor for aesthetic or moral transgression’ seems to mirror decadence, Adam Alston writes, reminding us that both concepts are slippery and versatile.[14] As decadence often bears negative connotations when utilised by prudes intending harsh criticism of non-normative attitudes and identities they consider ‘sick’, ‘sickness’ is likewise often espoused by marginalised persons or groups to attack oppressive conservative values.[15] Abstaining from the morose, mournful or earnest tone of some forms of activism, which equally marks many works dealing with illness, Bowery’s ‘sick’ performance can be read as a reclamation of decadence to confront the homophobic view of HIV/AIDS as a catastrophic consequence of moral decline and lewdness. More than any other stigmatising disease that acquires specific meanings, HIV/AIDS was at the time (and remained for many years) one that induced a particularly burdensome amount of guilt and shame. These damaging meanings would not just fade of their own accord. They had to ‘be exposed, criticized, belabored, used up’, to borrow Susan Sontag’s words.[16] Like many performance artists living with life-threatening diseases who resort to ‘sickness’ to challenge the negative meanings and preconceptions attached to their condition, Bowery orchestrated a gross spectacle anchored in burlesque bodily transgression that could allow for a similar effect. Nonetheless, he refrained from dealing directly with his HIV-positive status in all his performances.

Trapped in a perfected image of fabulousness, Bowery was terrified of the thought that people would pity him or translate his outrageous behaviour and performances (which often involved bodily fluids and simulated vomiting) as mere anger induced by his illness. Not unreasonably, however, the only scholarly reading of the performance at the AIDS benefit, posthumously by Alison Bancroft, could not ignore the catalytic role his diagnosis might have played in the work. Bancroft deciphers Bowery’s scatological enthusiasm as a conduit for ‘a troubled queer corporeality that is under attack’, rather than just a humorous prank intended to shock.[17] As a medical procedure that can also be used as a hygienic preparation for anal sex, and which may also be sexually stimulating along the lines of sadomasochistic play, the enema gives emphasis to the anus both as an area of gay desire and the entrance of the virus into the body via anal penetration. Bowery’s body then turns into a metonymy of his personal experience with a terrible life-threatening disease, with the enema on stage culminating in a decadent spectacle of abjection, where boundaries collapse, corporeal integrity diminishes, and liminal subjectivities between life and death come to the fore, disturbing the order of things.[18]

Conditioned by the terrorising victimisation of people living with the virus, Bowery’s subversive performance can be viewed as a frustrated backlash of exasperation mediated by abject humour that aims to disrupt our assumptions, emotions, and perspectives. His valuable contribution as an artist who eventually died from AIDS complications is his perpetual lust for life and creativity, which he deliberately refused to take the chance of tarnishing by coming out as sick and surrendering himself to public pity. His determination to keep up with his glamourous lifestyle, auspiciously afforded by his overall good health until he was hospitalised shortly before he died, debunked the fantasy of a haggard queer corporeality suffering because of depraved sexual habits: a popular representation that became a trite symbol in the service of veiled homophobia. It is for this reason that Bowery’s queer body deserves to be seen in the aftermath of his death as triumphant and glorious. By manipulating, altering, and glamming up the body, Bowery performed his own decadent resistance to normativity and the cultural politics of illness, for he decisively exercised the right to be in control of one’s body. Whether this right is asserted by deeply and openly engaging in ‘sick’ sadomasochistic practices – as artists Bob Flanagan (with Sheree Rose) and Ron Athey do for instance – or by Bowery’s means, it remains, in essence, a shared objective among those who feel excluded from or disparaged in dominant discourses and representations.

Approaching the 30th anniversary of his death, Bowery remains a subcultural and queer club icon, an inspirational figure for contemporary fashion design, and an enigma that continues to unfold for performance art scholars. Intriguing characters like Bowery flourish as fascinating dandyish counterpoints during grim times of societal collapse. The 1980s, with their extreme highs and lows, admittedly shaped his peculiar aesthetics and provided the dramatic backdrop for his performance of decadence. A visual provocateur with an unfathomable obsession with pure artifice, exhibitionism and extravagance, Bowery, as writer and critic Hilton Als aptly commented, signifies, thus, the postmodern ‘dandy who soiled Wilde’s velvets with vomit’.[19]

Dr Sofia Vranou is an associate lecturer at Queen Mary, University of London. Her first monograph on Leigh Bowery’s live art and performative costuming will be published by Intellect Books in 2025.

Notes

[1] Mae West, Goodness Had Nothing to Do with It: The Autobiography of Mae West (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1959), p. 268.

[2] Fiona Russell Powell, ‘Penthouse’, i-D: The Inside Out issue, October 1984, pp. 8-9 (p. 8). PP.22.J, Periodicals, National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum.

[3] Leigh Bowery in The Legend of Leigh Bowery, dir. by Charles Atlas (London: BBC4, 2008) [DVD].

[4] Sue Tilley, Leigh Bowery: The Life and Times of an Icon (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1997), p. 52.

[5] Dave Haslam, Life After Dark: A History of British Nightclubs and Music Venues (London: Simon and Schuster, 2015), p. 315.

[6] Richard Torry in The Legend of Leigh Bowery.

[7] Alix Sharkey Qtd. in Tilley, p. 58.

[8] Thomas Mießgang, ‘Die Kunst des Ausgehens: Wie Leigh Bowery im Rausch des Londoner Nachtlebens seinen Körper lesbar machte und als Regisseur eines Theaters der Künstlichkeit in Erdcheinung trat’, in Leigh Bowery: Verwandlungskünstler, ed. by Angela Stief (Vienna: Meyer, Piet Verlag, 2015), pp. 53-71 (p. 57). My translation.

[9] Charles Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, ed. and trans. by Jonathan Mayne (New York: Da Capo Press, 1986), pp. 1-40 (p.28).

[10] See Simon Watney, Policing Desire: Pornography, AIDS and the Media (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987).

[11] Tilley, p. 199.

[12] Ibid., p. 200.

[13] Qtd. in Ibid.

[14] Adam Alston, ‘Survival of the Sickest: On Decadence, Disease, and the Performing Body’, Volupté: Interdisciplinary Journal of Decadence Studies, 4.2 (Winter 2021), 130-56 (p. 130).

[15] Ibid.

[16] Susan Sontag, AIDS and Its Metaphors (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1989), p. 94.

[17] Alison Bancroft, ‘Leigh Bowery: Queer in Fashion, Queer in Art’, Sexualities, 15.1 (2012), 68-79 (p. 75).

[18] Ibid., pp. 75-6.

[19] Hilton Als, ‘Cruel Story of Youth’, in Leigh Bowery, ed. by Robert Violette (London: Violette Editions, 1998), pp. 10-25 (p. 18).