Times Square’s Theatre of Sex

A Staging Decadence Long Read

Guest post: Tom Garretson

Tom Garretson is a multi-disciplinary Native American/Norwegian artist working in the fields of art photography, music, writing, and theatre. He is also a music industry and arts professional, having worked in these fields for the past 40 years. He has collaborated, worked with, and produced artists such as Lydia Lunch and Annie Sprinkle, as well as produced many concerts for artists such as Dame Kiri Kanawa, Shirley Bassey, Sarah Brightman, and others. His art works have been exhibited in the USA, China and Norway, and his photographs and writings have been published internationally. For more information: www.tomgarretson.com

In this ‘Long Read’ for Staging Decadence, Tom paints a vivid picture of the sex theatre scene in and around New York’s Times Square in the second half of the twentieth century, drawing on personal anecdote as well as interviews with producers, performers and others involved in the scene at the time, among other sources. The result is an evocative sense not so much of a city in decline, as of a controversial subculture that emerged from the cracks.

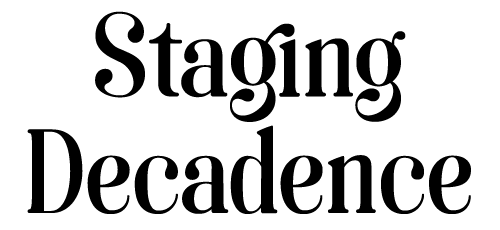

Contemporary critics looking back on New York City’s Times Square during the late 1960s through until the 1980s often deride it as a cesspool of decadence and decay.[1] Films such as Taxi Driver (1976) and Midnight Cowboy (1969) and the recent HBO series The Deuce (2017-19) also helped strengthen public perceptions of the areas’ notorious reputation for sex, sin, and debauchery. Drugs, pornography, crime, and human misery were plentiful on its adjacent avenues accompanied by rampant political and police corruption, set in an urban landscape in decline. This was the era of Son of Sam, rising murder rates, increasing heroin addiction, and widespread poverty. Apartment buildings were set on fire by greedy landlords cashing in on their insurance policies, punk rock rose as a cultural force, and crack cocaine and AIDS emerged to wreak havoc on 1980s New York.

Fig. 1: New York Mayor Abe Beame holds up a notorious Daily News front page from 30 October 1975, which purports to represent the words of President Gerald Ford after he refused to bail out a city on the verge of bankruptcy. Photograph: New York Daily News Archive.

Yet the area surrounding 42nd Street and Times Square together with its corresponding Eighth Avenue could also be understood as a netherworld that gave free expression to sexuality and desire, and inspired new forms of creativity, however much the dominant society sought to suppress it. From the smouldering flames of sin rose a creative resonance that is still felt in theatre, literature, music and in the visual arts. In the area’s peep shows, live sex shows, strip clubs and venues, there occurred a liminal development in artistic expression that transformed into a variety of artistic output, created by select people who worked as prostitutes, sex performers, or as employees in the adult entertainment industry.

This post will focus on examining the environment of Times Square’s sex theatres and how certain actors, artists, writers, and musicians intersected with the sex industry during these years as a form of radical theatre, using this as a platform for developing their own artistic personas, and how it served as a transitional phase from the erotic to the creative. It is the creative and social intersections between sex work, art and artists that I will be addressing here.

From burlesque to sex

Once the glittering centre of the musical and dramatic stage, the area around Times Square regressed in a steady decline after the Great Depression of the 1930s. Marquees that once proudly announced George Gershwin, Irving Berlin, Cole Porter and Ziegfeld fell into economic difficulties and began to either close or were transformed into cheap movie theatres or burlesque show halls. Most notably, the Minsky Brothers opened their infamous Minsky’s Burlesque at the Republic, continuing their tradition of staging risqué burlesque dancers and innovating the catwalk platform into the audience. Legendary strippers such as Gypsy Rose Lee, Ann Corio, Lili St. Cyr and Dixie Evans bumped and grinded their way across the stage, set to elaborate routines and staging, accompanied by a small pit orchestra playing carefully-selected songs suited to their choreography. Dixie Evans recalled:

When they’d announce Lili St. Cyr the big timpani would roll. Oh boy! Incomparable! You could not compare her to anyone or anything. It was magic, everything she did. One of her biggest acts that made her the most famous was her act in a glass bathtub with golden legs. She would be in pink and blue bubbles, which would be floating up and over the audience. She would descend these glass stairs and into the set, and of course had all these props. The maid would give her all these different gowns, and all of this was to show off her ballet! She’d do this ballet all across the stage in different gowns. She’d do this routine about ‘No, I don't want to wear that dress tonight’, you could see what she was saying, and the maid would give her another dress, and the mood would change and she’d do something else. At the end of the act she’d have on white gloves and a rose, and a white hat and gown, and you knew that this was the right dress that she wanted. The maid would put on her shoulders a full-length diamond-mink coat, and she would then leave the stage. That was just one act.[2]

This was the tradition set by burlesque in Times Square, which later sex show theatre performers would emulate, but perhaps not as spectacularly. Burlesque provided affordable entertainment for the working class, and cheap thrills and laughs with famous comedians such Abbot and Costello, Phil Silvers, and Red Skelton, who appeared alongside the strippers that titillated their audience. Outraged citizens groups protested burlesque’s nudity, and after one too many fallen G-strings and missing nipple tassels, the guardians of morality finally succeeded in closing burlesque in Times Square in 1937 (though it continued elsewhere into the 1950s). Little did they know what was to come after. The demise of burlesque set the stage for something far more explicit.

Increasingly Times Square regressed in the popular imagination as a cesspool of filth and squalor, even though it remained immensely popular with a curious public. By the 1950s bribes to corrupt policemen insured a blind eye to the sales of pornography in the many small magazine shops on its side streets, and the Mafia quickly moved in to acquire property or rentals to exploit the demand for it. Theatre owners soon realised there was easy money in showing porn, and transformed their once grand, now decaying, palaces of theatrical entertainment into erotic movie venues.[3] By the 1960s and 1970s these glorious movie palaces and theatres had deteriorated into pale ghosts of their former splendor, replaced with gilded stucco ceilings damaged by leaking roofs, red velour seating now stained and shredded, and peeling paint hanging from its walls. The decay was also evident throughout the city.

Officially located in the intersection of Broadway and 42nd Street and named after the New York Times building, Times Square’s demise attracted an odd mixture of society’s demographics. Pimps, prostitutes, hustlers, drug pushers, and thieves all mixed with families on their way to see a more ‘legitimate’ show a few blocks north. Card sharks set up their make-shift cardboard box tables to lure a mark into a Three-Card Monte, as shop owners lingered in doorways, puffing on cigarettes, coolly eyeing by-passers before trying to rope one into their stores. The ever-present stench of sulphur rose from subway air shafts, mixing in with the smell of urine, beer, and cigars. Endless Yellow Cabs drove through the streets dodging junkies and tourists as the mentally ill shrieked and halleluiah-pastors praised the Lord. And woe to anyone making eye contact with a small-time grifter standing on the sidewalk, lest you be solicited for sex, dope, or getting mugged. This was the theatre of the street set to a musical cacophony of harsh car horns, screeching bus breaks, laughter, screams, and solicitations from menacing figures: welcome to Times Square.[4]

By the late 1960s porn theatres, peep shows, and strip clubs began opening all over the Times Square area. Obscenity laws had widely regulated adult entertainment even though what constituted as illegal and ‘obscene’ often varied and was subject to both legal and content interpretation. In 1970, The Report of the Commission on Obscenity and Pornography was published by the US government and failed to find any major negative effects in viewing or using pornography, much to the dismay of outraged conservative citizen groups, yet it still couldn’t help but bring religion into the discussion in a desperate attempt to chastise it.[5] The 1973 Supreme Court decision in Miller v. California established a three-pronged test to determine if material was obscene: it considered local community standards, whether the material appealed to prurient interests, and whether it lacked serious artistic, literary, political, or scientific value. In the end its ruling judged that ‘all ideas having even the slightest redeeming social importance… have the full protection of the guaranties [of the First Amendment]’, and overturned earlier convictions against obscenity.[6] Several other landmark legal cases emerged during this period that had a lasting impact on the regulation of sex theatres, contributing to the legal framework that allowed for easier access to adult entertainment. With each new ruling in favour of freedom of speech, Times Square venues such as The Big Apple, Show World, The Adonis theatre, Circus Cinema, and the Grand Pussycat theatre pushed the envelope further, displaying more flesh and challenging its performers to indulge in increasingly explicit performances.

Prostitution laws in New York strictly prohibited the sale, promotion or profiting from sale of sex. In Times Square these laws were rarely enforced, even though such laws applied to both the prostitute, their johns, and any responsible owners of establishments they might solicit in.[7] Many theatres, strip clubs and venues kept close watch on any dancer who solicited and would promptly fire any performer caught doing so. A house could lose their liquor license or be closed if a transaction occurred between a performer and audience member. Sometimes the police would monitor the theatres, but it was generally well-known that the Gambino and Genovese crime families paid bribes to corrupt cops to keep their theatres open.[8] Other venues were laxer, and prostitution flourished.

In the gay oriented theatres, police rarely dared venture a visit due to their homophobia, in contrast to their constant raids and entrapment outside the area. Queer theatres openly allowed for cruising, and although hustling in most theatres was prohibited, most owners usually turned a blind eye. A darkened back room was provided for dancer/escorts to engage in sex with customers or for those seeking anonymous sex.[9]

Many female performers who did not want to engage in prostitution considered this kind of erotic work as a safe form of employment, earning far more than they could in, say, retail or restaurant work. Additional tips could be made in lap or table dances or ‘private dances’, and even though at times the boundaries might be blurred, the performer was usually in control. In contrast, some of the patrons specifically did not seek sex but conversation or human contact instead.[10] Sometimes the fantasy of sex is more important than the reality, and this would be understood and fully exploited by the performer. Nonetheless, many sex theatres or peep shows existed in a kind of hypocritical, parallel reality where venue owners prohibited prostitution with threats to any performer who openly solicited, even if many performers often did exactly that.

Fig. 2: A peace march in Times Square in April 1972. The Follies Burlesk, pictured here, later became the Gaiety Male Burlesk in 1976. Photo by Bob Gruen. Public domain.

Some performers have expressed a sense of empowerment through their work, using it as a means of exploring their sexuality or challenging societal norms. However, this sense of empowerment coexisted with the potential for exploitation, as performers were often working within an industry that could be marked by precarious working conditions and uneven power dynamics. Most establishments were owned by men and the women who worked in these most often had a difficult relationship with them. A few theatres were owned by women, such as the Gaiety Burlesque and the Harmony theatre, but most sex performers were inadequately paid, and it was only through tipping that good income could be earned. The exceptions were the sex theatre shows, which were more lucrative for the performers.

New York attempted to regulate adult businesses through its zoning laws. However, like censorship, these efforts faced legal challenges on the grounds of freedom of expression. Even so, Times Square became notorious for its concentration of adult theatres, peep shows, and other adult entertainment establishments, synonymous with sex and sleaze, in a constant battle between proponents of free speech and those advocating for stricter regulation. As cultural attitudes towards sex began to evolve, pressure against sexually-oriented business lessened, even though the city applied strict ordinances against them, such as licensing requirements, restrictions on operating hours, and guidelines for the physical layout of establishments. Regulation of adult entertainment across different neighbourhoods in New York City varied due to interpretation of community standards and local jurisdictions enforcing their own standards regarding what was considered obscene.

As societal attitudes toward sexual content in public spaces began to change, so too did the social urban landscape surrounding Times Square. The late 1960s and 1970s saw the emergence of the sexual liberation movement, which advocated for greater openness and acceptance of diverse sexual expressions. Challenges to traditional norms of sexuality led to a more permissive attitude towards sexual content. The rise of the counterculture and changes in artistic styles attracted writers, artists and performers to the district seeking new forms of expression and experimentation. Sexual content became just one method to challenge conservative values.

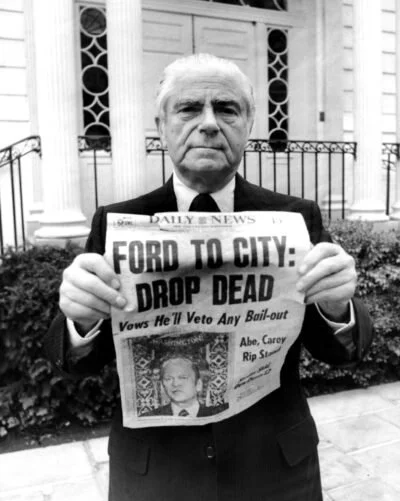

Fig. 3: Cover of Screw: The Sex Review, no. 15, 30 May 1969. Edited by Al Goldstein. Public domain.

Media representations and public discourse also played a role in shaping societal attitudes toward sexual content, with newspapers such as the Village Voice openly advertising the sex theatres and cinemas, and magazines like Screw reporting on the activities that occurred there. A more liberalised discourse on sexuality permeated New York’s newspapers, the arts, and its theatres. Economic factors weighed in as well. When the area fell into hard times it was the adult entertainment industry that created a positive economic impact by creating a variety of jobs, from performers, staff, maintenance, and security.[11] Transportation bloomed, and the food vendors and hotels surrounding the area benefited from an influx of visitors. This helped correct the overall economic decline and urban decay,[12] even if the tawdry neon signs announcing sex and nude performances wasn’t to everyone’s taste. But the adult entertainment industry in Times Square operated as a business model that could thrive in the face of economic challenges. The relatively low overhead costs, combined with the potential for high-profit margins, made sex theatres and related businesses attractive ventures for entrepreneurs willing to navigate the legal and social complexities. It capitalised on the demand for adult entertainment and Times Square remained a major tourist and entertainment hub alongside the more ‘legit’ theatres on Broadway and its side streets.

Pushing the limits of performance

The sex theatres established in Times Square during the late 1960s to the 1980s held significant cultural and historical importance in being a kind of performative theatre that existed outside of the cultural hegemony, and that became influential to the arts despite it. While their explicit content and adult nature often attracted controversy and moral panic in the media, these establishments played a distinct role in the cultural landscape of the time, especially for artists emerging from the underground arts scene. These performers, actors, writers, musicians, and artists used sex theatres and venues to challenge conventional societal norms by presenting explicit and provocative content that pushed the boundaries of what was considered acceptable in mainstream culture – as well as in the norms of erotic performance.

Some of these performances often addressed taboo subjects, gender, and power dynamics. Seka, the sex worker and porn star, was so immensely popular in her live performances in the 1970s that her appearances at the Melody Burlesk created lines of men waiting down the street to see one of her shows. After the completion of her performance, she would sit ‘spread-eagled onstage, and men would line up to give her a lick for one dollar’.[13] The three-story sex emporium Show World permitted female performers to push the envelope in ways previously unthinkable. Monika Kennedy had a huge following with her outrageous and comedic sex shows in the 1970s and 80s that encouraged audience participation. Having crossed from burlesque to hard-core sex shows, her acts featured increasingly audacious displays of sex before – and often with – audience members. For Independence Day, she dyed her pubic hair red, white and blue in a patriotic tribute.[14] By 1972 her shows became increasingly bolder, and she could be seen lifting chianti bottles with her vagina, along with sparklers, audience spectacles, and, in one case, an audience member’s toupee. She appeared onstage in a cowgirl outfit, complete with a holster and guns, flavoured douches, whipped cream, and enticed her audience to ‘come on baby, it’s feeding time’.[15] She also toured with her own rock band named Monika Kennedy and the Family Jewels, and pursued a recording career away from the sex industry.

The theatres encouraged diverse collaborations, creating an interdisciplinary approach to sex performance by using performers from various artistic backgrounds, including actors, dancers, writers, musicians, and visual artists, coming together to create genre-breaking works with sexual content. After all, variation, the rare and the odd always sold more tickets. It challenged the limitations of what was allowed to be seen by the public in terms of provocative and explicit content, sometimes so graphic that it left nothing to the imagination. The stripper Honeysuckle Divine was notorious for her use of ‘pussy theatrics’. She would distribute newspaper sheets rolled into cones to audience members, then perform to Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture by shooting ping-pong balls out of her vagina in perfect timing to the orchestra’s canon ball explosions, accompanied with talcum-powder smoke. She would also play the recorder with her vagina, while telling the audience of her marvellous muscle control, and even take requests. When she performed outside of Times Square, her shows would often be raided by the police and closed. Honeysuckle Divine’s performances were an odd mixture of the erotic with the absurd, comedic, and outrageous, even slapstick, resulting in an environment of scandalous fun.

Fig. 4: Honeysuckle Divine & Busty Russell in 1979. The Daniel D. Teoli Jr. Archive. Public domain.

The theatre of sex placed a strong emphasis on the physical and visual aspects of performance, often pushing boundaries and challenging both laws and conventions. It was a form of theatre that emphasised the visceral over the word, the experiential over objective distance, and took the art of the tease to an extreme. As the constraints surrounding erotic performance relaxed, the intersection between art and eroticism also became blurred, both on the stage and within the culture at large.

One of the artists known best for bringing together sex work and art is the ex-porn star turned performance artist Annie Sprinkle. Following the tradition of Kennedy’s Show World performances, Sprinkle went even further in creating a career in pornography and live sex shows that progressively began to incorporate more creative elements in her work. As a stripper, she performed her ‘Strip Speak’ that contained improvised erotic spoken word while encouraging the audience to masturbate.[16] Her stage performances became more and more imaginatively staged, with dolls, costumes, and at times openly revealed a Tampax string hanging out of her vagina as a feminist statement. Her shows might include a male blow-up doll that she would fellate or ask her audience direct questions on their sexual techniques, and she would dress in a variation of costumes including a nurse’s outfit or aerobics instructor. Sometimes she used a water squirt gun for both her and her audience while leading them into an erotic theatrical journey of desire. Sprinkle’s appearances at the Show World theatre created an erotically charged environment enhanced with her acting experience from porn films and an innate drive to become an artist. ‘I did gain the skills and confidence I would need for further stage performances in the art world’, she later wrote.[17]

By the late 1970s, the Times Square sex shows had become more immersive and participatory. As the fourth wall crumbled, direct interaction between performer and spectator allowed for a more intimate atmosphere. Some theatres often incorporated multimedia elements into their performances. This could include the use of film, slideshows, projections, and other visual aids to enhance the storytelling of a sexual fantasy and create a more layered experience. Music also played a crucial role. Live musical performances, soundscapes, and experimental use of audio elements contributed to the overall sensory experience and added layers of meaning to the performances.

The actor prepares

All sex performers were expected to create their own costumes, clothing, make up, lighting, music, choreography, and show concepts to sell tickets. The performer created ‘the play’ to be performed in front of their audience. These sex theatres provided an environment where explicit content was presented as a form of artistic expression. Sprinkle’s work especially represented this as she transitioned from sex worker to performance artist in the early 1980s. By 1989, she was working with the experimental, underground theatre director Emilio Cubeiro, known primarily for his plays with Lydia Lunch. Together with ex-Warhol Factory actor/David Bowie tour manager/foundational figure from the underground theatre scene Tony Zanetta, they staged Sprinkle’s ground-breaking Post-Porn Modernist (1989) show at the Harmony theatre (previously the Melody Burlesk). Sprinkle’s work fused art with sex, porn with purpose, and truly broke down the barriers separating the two. Her evolvement into documentary filmmaking, writing, and live performance art further enhanced her reputation as an artist, and she has never regretted her past in sex work or as a sex performer. Using Cubeiro’s hard-hitting style and Zanetta’s past performance experience with the Theatre of the Ridiculous, Sprinkle created a humorous and multi-layered performance describing her life in pornography, as a prostitute, and as a sex performer using film, slideshows, and theatrical monologues in elaborate set designs. The show later moved downtown to The Kitchen, an established artist-driven collective performance space. Zanetta recalls that the audience would often be a bizarre mixture of artists, intellectuals, and men in raincoats from the Show World crowd who came there to masturbate, but who were sorely disappointed by the lack of sex in that show.[18] It was this mixture of underground, queer-oriented theatre with a Show World performer that created a new dimension in performance art and further influenced other performance artists to explore their own background in sex work. Later, culminating in the political ‘scandals’ of the Corcoran Gallery and other American exhibition spaces featuring works by Robert Mapplethorpe, Andres Serrano and Karen Finley, her Public Cervix Announcement (1990) would be used as evidence by Republican Senators to defund the National Endowment for the Arts and to censor artists who used sexuality in their works.

Performances in Times Square’s theatres of sex often incorporated elements of both visual and performing arts, challenging traditional boundaries and definitions of what constituted ‘art’. It broke the down the barriers set by established critics and curators of art and theatre, disregarding their power, and subverting their authority. And this is exactly what art in the tradition of the Impressionists, the Futurists, and the Dadaists had done before them, in destroying rigid cultural norms installed by patriarchal power structures and reclaiming the right of creative expression without the limitations of ‘good taste’ or conventional boundaries. When artists worked as sex performers the fusion of ‘High Art’ and ‘Low Art’ was transgressed by their exploration of taboos, and in their disregard for distinctions, hierarchies, and genres.

As in traditional theatre, fantasy and escapism both played important parts. The psychological interplay between performers and the audience often revolved around the creation and consumption of fantasy. For instance, writer and spoken-word performer Zoe Hansen spoke to me about her time in New York as a dominatrix and brothel owner, when she excelled at a kind of improvisational theatre to fulfil the client’s wishes. These often would include elaborate staging to suit the client’s demands – lighting, furniture, objects in the room, clothing – and she would perform the role to suit the fantasy without breaking the illusion. The fantasy became the play, and only at its completion would the illusion be terminated.[19] Roleplay in sex performance is a form of theatrical experience with or without sexual contact. The ‘script’ of the performance is understood and agreed to beforehand and may even include pre-written dialogue or objects that the customer has brought with them.

Erotic dancers and performers who did not engage with actual sexual contact with the audience were also required to create this fantasy world, at times using alternative tools to enhance their performances. In some venues there existed a kind of kiosk-booth in which the customer would insert dollar bills to make a metal curtain rise and reveal a nude woman behind a glass partition. The customer could talk to her, and she would encourage him to masturbate, albeit interrupted by the curtain coming down again and the customer having to quickly insert more money into the machine. Sometimes the partition could be removed for more direct (and pricier) transactions between the performer and viewer. At all times the performer would strive to maintain the illusion (though actual sexual arousal by the stripper was frowned upon by her colleagues).[20] Other theatres featured a circular array of booths that surrounded an enclosed stage with a mattress or pillows, on which either one or several male and female performers would engage in simulated sex. Here, too, the viewer would be expected to keep ‘feeding the machine’ with dollar bills to view the performance. In each case, the performer created an illusion of sex by playing on the customer’s sexual fantasies and enticing them. Sometimes they would engage in conversation with the customers who were hidden in their booths with only their faces observable. Tipping was strongly encouraged for as long as the fantasy continued to its final climax.

As a typical example of the Times Square sex theatres, The Bryant theatre featured live sex shows in five performances a day between ten in the morning and ten at night, where a male and female performer would appear semi-nude on a blue-lit stage, on a circular bed that would slowly revolve. The female performer would first strip for the audience and her partner, then fellate him followed by cunnilingus on her, followed by penetration without orgasm for twenty minutes.[21] This would be repeated six or seven times a day. Sometimes this would feature the addition of costumes, sets, or even props. At the Psychedelic Burlesk theatre you could find a popular show featuring a male performer dressed as Abraham Lincoln, complete with beard and a stovepipe hat, performing the sex life of the President with a female companion.[22] Live sex shows were the most lucrative, and often lovers or married partners would perform together, sometimes before a packed audience of 300.

Fusion with the punk and arts scene

With the rise of punk rock, it was natural that creative nightclubs such as CBGBs and Max’s Kansas City drew sex workers, just as venues such as Show World drew musicians from that scene. The visual artist Rod Swensen painted sex performers and produced their shows in Times Square, as well as produced live shows for acts like Patti Smith, and shot videos for Blondie, the Dead Boys, and the Ramones. ‘I liked CBGBs for the same reason I liked Eight Avenue’, he stated. ‘I thought it was explosive and dynamic and exciting and real’.[23] These underground art and music venues in the New York punk scene shared an interconnectedness with the sex industry of Times Square. Sex performers and musicians intermingled freely in both, engaging in an atmosphere of creative cross-pollination. Drummer Tim Connelly, who played with John Cale and Richard Hell, performed in live sex shows written and directed by Swenson at Show World. Blues musician Candy Kane could be seen onstage stripping with her electric guitar, playing and dancing.[24] Dee Dee Ramone danced at the Gaiety Burlesque and hustled in Times Square as well as on 53rd and Third Avenue, which he also wrote a song about. The list goes on, as the attraction of art, music and sex work conjoined. Uptown Times Square and the downtown art and music scene were closer than the many streets that separated them.

Some sex theatre actors used their performances as a form of political and social commentary, seeking a more immersive experience in direct communication with the audience. The barrier between audience and performer vanished. The sex actors created spaces for the exploration of human sexuality and desire in a more open and explicit manner. These performances often engaged with the complexities of sexual relationships, personal fantasies, and the varied expressions of desire that were often marginalised or ignored in mainstream theatre. Rod Swenson remembers: ‘The extent to which art confronts the status quo or conventional ways of seeing and thinking… that’s a measure of how important it is. Things that pass as art are often just imitative or redundant, so they are measured by how well they imitate some already existing ideal or model. That’s always been extremely boring and meaningless to me’.[25] Swenson wanted confrontation in both sex performance and music, and to revolutionise theatre by taking risks. Mixing political satire with sexual taboo seemed like the perfect way to shock people out of their mediocrity. Five shows a day, seven days a week in ‘short format, fast-paced vignettes, typically intentionally absurd and comedic, often with erotic themes, each running for about 20 minutes for a total show of about an hour and a half backed with a lot of cutting-edge music’. This, he stated, was a political act: ‘It’s a total imbalance of values and pure hypocrisy for America to condone and permit a brutal and violent exhibition like prize-fighting, while sex on stage in all its forms is one of the very most important and beautiful things in life, and until people in general – and society at large – achieve public consciousness of this, we’re all living a lie’.[26]

Swenson’s productions at Show World included absurdist themes such as Captain Kink’s Sex Fantasy Theatre (1976), where a Dr. Marx appeared in puppet form and ejaculated all over the audience. The shows proved immensely popular, contained hard core sexual acts, and with newly written shows being performed every Monday to sell-out crowds. This also included musicians and artists from the CBGB’s crowd, who also worked on the lighting, sound or with props. He included Monika Kennedy in his shows believing that her direct contact with the audience was a form of agit-prop theatre.

Fig. 5: Wendy O. Williams and the bass player Chosei Funahara in a promo shot for the Plasmatics. 16 July 1979. Public domain.

After answering a newspaper advert placed by Swenson calling for performance artists, Wendy O. Williams showed up at Show World and was hired. Swenson loved Williams’ aura of menacing raunchiness, especially after she knocked out an audience member who overstepped his boundaries. The shows were raided by the police numerous times, yet they continued until the theatre was closed by Mayor Abe Beame in the Spring of 1977. Swenson persisted and the theatre reopened after the noise had died down. Williams took the centre of attention now, combining live sex with her brash aggressive attitude and punk posturing. It wasn’t long before Swenson struck on the idea of creating a band with Williams at the forefront, in a concept that mixed punk rock with performance art, heaped with plenty of explicit sexuality. His stagehands included the painter Michael David and guitarist Richie Stotts who performed in a punk band called The Numbers, and he convinced them to back Williams, giving birth to The Plasmatics. After their debut at CBGBs, the band exploded on the punk scene, becoming renowned for Williams’ audacious performances that included electrical tape in an ‘X’ on her nipples and bare breasts, threatening the audience with a chainsaw and using it to cut guitars in half, and destroying television sets with a sledgehammer on stage. The rest of the band also played their part, with Stotts sometimes dressing in a nurse’s uniform or tutu and sporting a mohawk hairdo (inspired by Taxi Driver). The band became something of an overnight sensation and quickly moved to larger music venues such as Irving Plaza, and then selling out the 3,300 capacity Palladium – all without a major label recording contract. The latter show featured blowing up a Cadillac car onstage. Their music mixed punk with metal, topped with Williams’ abrasive, rough vocals. From Show World to the concert stage, Swenson and The Plasmatics challenged their audiences to wake up, reject consumerist society, and confront misogynistic critics in the media. Williams would ultimately receive a Grammy nomination in 1985 for ‘Best Female Rock Vocal’. From Bob Swenson’s theatrical sex shows to the punk rock stage, popular music now welcomed the influx of politicised and sexualised performance strategies.

Queer sex performance

Although gay sex theatres didn’t present elaborate sex shows of the kind performed in straight sex theatres, many theatres in Times Square were inclusive spaces that catered to LGBTQ+ communities. These theatres provided a platform for LGBTQ+ performers and patrons to express themselves freely at a time when societal attitudes toward non-heteronormative expressions of sexuality were more restrictive. Overall, most gay-oriented venues appealed to men, presenting films and performers that portrayed a more masculine flair. This included cowboy costumes, construction site clothing with a hard hat, black leather jackets and jeans, James Bond, the Sailor, or other iconography from male homoerotic fantasies. All dancers were expected to have their own pre-selected songs, costumes, and dance choreography.[27] Some theatres held amateur nights, where fresh talent could be shown, and the winner would receive a cash prize. For all, the most important quality was to be able to build a rapport with the audience and rope in regular customers.

Male dancers on the stage were expected to strip, show their erect genitals, and in some cases masturbate to ejaculation which would then receive a resounding round of applause from the audience members. In the Gaiety Burlesque theatre, performers often engaged in prostitution, or ‘hustling’ after their show, where they would walk amongst the audience searching for clients and, if successful, disappear into a dark back room after negotiating their fee. However, not all the dancers were gay or engaged in hustling, as there were many heterosexual males that danced (and hustled) in these venues too. There was easy money to be made.

Sometimes members of the audience would masturbate openly as others stuffed dollar bills into the dancer’s jockstraps or boots. In certain theatres the dancer might come down from the stage and into the audience as part of their performance, allowing themselves to be touched or stroked or sometimes even fellated by an audience member. Here, as in the straight theatres, it was the dancer who set the limit of his performance and how explicit it would get. Most venues showed porn films between dancer’s acts.

The unique environment of Times Square influenced not only the content but also the style of writing and performance. The narrative structures within sex theatres were often experimental and unconventional. This could involve fragmented storytelling, nonlinear narratives, and abstract representations, challenging the linear and straightforward storytelling found in traditional theatre. Many artists incorporated elements of this kind of language, from the diversity of characters encountered, and the vibrant energy of the street into their work. Their experiences as artists and writers were diverse, and the impact on an individual’s artistic development often depended on their personal perspective, the specific circumstances of their involvement, and the creative choices they made in response to their experiences. The writer, artist and actor David Wojnarowicz captured the voices of the many characters in Times Square, where he hustled for income, in his book The Waterfront Journals (1997). In it, he conveys his subject’s truncated, idiomatic speech of the street, flavoured by Latino or Black American accents. Many other gay and straight men have written biographies about their sex work experiences in Times Square, such as Josh Alan Friedman’s Tales of Times Square (2007). Their style and use of language was inspired – or at least influenced – by the environment of sex work.

Artists surviving

Many artists that emerged out of their experiences as sex-workers, strippers, performers or employees in New York City transitioned into theatre, performance art, filmmaking, literature, and even in visual art in various ways. Each of these artist’s experiences were different, and each brought something unique into their expression. Performance artist Penny Arcade drew on her experience of prostitution in her live theatre performances, discussing both its negative and positive aspects. Her performances sometimes used actual sex workers, strippers, and dancers. She is assertive in stating that prostitution does not an artist make, but that it is the artist who chooses sex work. In her play Bad Reputation (1997), she sought to portray the connection between sexual abuse, addiction, and prostitution, and cited the censorship that occurred during the 1980s from conservative Republican senators against the NEA as a provocation for including her background in her work.[28] Storytelling and narrative exploration became a feature of her performances. Many other artists such as Lydia Lunch have also transformed their experiences into artmaking, such as her biographical novel Paradoxia (1997), and in her performance art and spoken-word stage performances. Lunch briefly worked in prostitution and stripping out of a need to get her band Teenage Jesus and the Jerks to London and to pay for air travel for the musicians.[29]

All the artists I’ve spoken to in researching for this post consciously challenge societal perceptions and stereotypes and use performance art to express their experiences, emotions, and perspectives, incorporating elements of their past into present work. They have created works that serve as a form of advocacy, activism and political agency against the dominant culture. All of them break down the myths and misconceptions surrounding sex work and artistic output, and challenge their audiences to reconsider their own prejudices. The rebellious nature of the sex industry attracted many creative people to it for work. Not only was it easier money to acquire than ‘straight’ employment; it also offered rebellion and defiance against societal norms. The fight for freedom of speech, artistic liberty, and sex-positive feminism were often used as a reason for being attracted to the industry. As the conservative Republicans took control in the US, often artists’ performances served as a counter-reaction with subtle or blatant political and social commentary.

Sex work in Times Square was not always a choice but most often an economic necessity for artists. While some have used their past experiences as positive affirmation, others have experienced it as exploitative and traumatic. Novelist and playwright Kathy Acker briefly worked as a stripper in Times Square and did sex shows there with her boyfriend in 1971 to fund her writing.[30] Rising out of the punk and arts scene in New York, her works often focused on such themes as childhood trauma, rebellion and sexuality, sometimes using extreme imagery. Also, the performance artist, musician and actor Kembra Pfahler is noted for her work with Richard Kern’s Cinema of Transgression films and insists her previous work as a stripper and sex worker was a political act after moving to New York in 1976. She led the band The Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black, and performed nude with her body painted blue, wearing a black shock wig. She considered stripping as the start of her career as a performance artist.[31] She would crack eggs with her vulva and utilise many other associated objects from Times Square’s sex industry in the context of her art performances. Pfahler also appeared with sex worker Veronica Vera as well as Karen Finley, Annie Sprinkle and Emilio Cubeiro at The Kitchen in their Carnival of Sleaze in February of 1988.

The artist John Sex supplemented his income as an art student by stripping in Times Square’s gay theatres. He used this experience in his performances, where he’d often appear clad only in a jockstrap in clubs such as Danceteria, The Palladium, the Paradise Garage and the Pyramid Club, in self-written performance pieces. Sometimes he would be accompanied with a pet python, creating exaggerated characters that mixed gay go-go dancing, drag, and cabaret songs with a Las Vegas-style act. Also, Spalding Gray, who worked as an actor and writer and founded the Wooster Group theatre company with, among others, Willem Dafoe, wrote short pieces for the strippers appearing at Show World to enact on stage. He also appeared in three pornographic films in the mid-1970s before his work in films such as The Killing Fields (1984) and Swimming to Cambodia (1987). He would later write of his experience as a sex performer in his essay The Farmer’s Daughters (2011), where he describes his difficulty maintaining an erection in front of the camera during the filming of a porn film from 1976, even breaking down in tears due to the pressure from the director.

Transgendered actor Dominique Jackson, known from the TV series Pose (2018-21), has spoken openly in interviews about having to do sex work to survive. Many trans artists, actors and writers have experienced being marginalised to the extreme and have been forced to work in prostitution and sex work simply to exist. Many of these could be seen in Times Square. For all of these artists, sex work was a necessary pathway to enable their artmaking and provided an income when the alternative would have been detrimental to their output as artists.

The stigma associated with working in the adult entertainment industry affected both performers and their audience. Performers might have faced judgment and discrimination outside of their work environment, influencing their self-perception and mental well-being. Similarly, audience members may have faced social stigma for attending sex theatres, contributing to a shared sense of marginalisation. It is crucial to recognise that the experiences of individuals involved in sex work are diverse and multifaceted.

The performer’s individual experiences depended on their motivations, personal boundaries, and experiences in the workplace and within the psychological interplay during the performance itself. Some have embraced their work as a form of artistic expression, while others might have navigated the challenges with a sense of detachment or resignation and are unwilling to discuss their past. Certainly, the psychological toll on the mental health of performers cannot be overlooked. The nature of the work, combined with societal stigma and potential exploitation, designated them as outcasts from the dominant society, and may have contributed to stress, anxiety, and other mental health challenges. Support systems within the industry or external resources played a crucial role in mitigating these effects. As societal attitudes evolved and the economic landscape of Times Square changed, the dynamics between performers and their audience evolved, and the ecstatic dynamic of live sexual theatre became altered by the internet’s readily available access to hard core porn. The relationships between performers and their audience were shaped by such power dynamics, economic motivations, societal perceptions, and the unique environment of the adult entertainment in that era. And for some artists working in that industry, it would exert an influence on their later works long after they had left it behind.

Rise and fall

By the 1990s a variety of factors led to the decline of the adult industry in Times Square. Social, economic, and regulatory factors evolved over the preceding years in response to citizen groups, and urban land developers sought to move into the area to reclaim property for further exploitation. The transformation of Times Square from a seedy and gritty area to a more sanitised, family-friendly entertainment district played a central role in this decline.

Beginning in the 1980s and continuing into the 1990s, there was a concerted effort to gentrify and revitalise Times Square. Urban renewal initiatives sought to transform the area into a safer, more attractive destination for tourists and mainstream businesses. This led to a decline in the tolerance for adult entertainment venues, including sex theatres. Zoning regulations became more restrictive, limiting the locations where adult entertainment establishments could operate, and as Times Square underwent redevelopment, zoning laws pushed adult businesses out of prime real estate areas. The economic landscape of Times Square changed as property values increased. The demand for prime real estate in the area rose, making it financially lucrative for developers to invest in upscale entertainment, retail, and commercial spaces. This economic shift made it less viable for sex theatres to continue operating in those locations.[32]

Times Square increasingly became a tourist-friendly destination with a focus on family entertainment. The changing demographics of visitors to the area contributed to a shift in the types of businesses that thrived. The concern for safe, friendly tourism forced politicians to reconsider their previous acceptance of the sex industry.

Cultural attitudes toward sexuality also evolved over time, and mainstream society became more accepting of diverse expressions of sexuality. As a result, the explicit and seedy nature of sex theatres became less aligned with societal norms, reducing the demand for such establishments. Technological advances in home entertainment impacted the pornography industry significantly. VHS tapes and later the internet provided alternative and more private ways for individuals to access adult content. This reduced the appeal of public adult theatres. Also, the rise of virtual sex content online made the porn theatres and peep shows less relevant, as previously what would be experienced in dirty, grimy and sometimes dangerous venues could now be enjoyed in the safety of one’s own home.

The adult entertainment industry around Times Square had an impact on the dominant culture through the artists, writers, actors, and performers who worked there during the late 1960s through the 1980s, and who referenced their experiences in their theatre performances, music, artwork, books, and other works. These artists left an undeniable mark on popular culture as the dominant culture sought to explore and exploit the taboo aspects that these artists referenced. Film, television, music, photography, fashion, theatre, literature, and visual art have all taken their cues from it.

Fig. 6: A photo of John Sex screened at Madonna's Celebration Tour on 1 November 2023. Public domain.

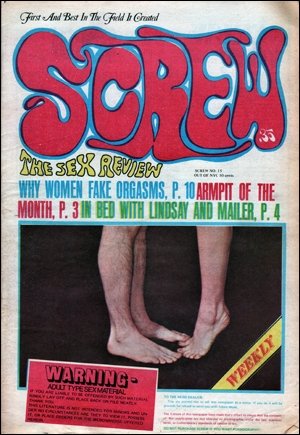

Popular music has taken visual and performative aspects from the sex theatres – think Britney Spears, Madonna, Beyoncé, and other popstars. Also, Madonna shot a segment of her photography book Sex (1992) in the Gaiety Male Burlesque theatre, using some of its dancers as models. Perhaps even more interestingly, traditional theatre venues started presenting plays and musicals based on the experiences of the sex workers and actors of Times Square. Most well-known of all these theatrical productions was Oh! Calcutta! (1969), which debuted Off-Broadway and after increasing popularity moved uptown to the Belasco theatre on 44th Street. The musical featured fully nude performers and even a segment written by John Lennon, as well as skits simulating sex, group sex, masturbation, and stripping. Also, other stage productions utilised the influence of the adult industry, such as The Oldest Profession (1987), about sex workers in New York and their lives as marginalised individuals; Rent (1996), which features a character who is a performer at a strip club; the musical The Life (1997), which focused on the lives of individual sex workers; and Hustlers (2016), in which a group of strippers devise a scheme to steal money from their wealthy Wall Street johns.

Fig. 7: Billboard for Oh! Calcutta! in Times Square,1981. Public domain.

*

Diverse collaborations created an interdisciplinary approach, resulting in an intermedial convergence of styles and ideas. The adult industry that included artists, writers, and actors during the late 1960s up through until the 1980s encouraged a more inclusive approach to artistic expression using sexuality. Naturally, not all sex performers were artists or actors. It’s important to note that while sex theatres pushed artistic boundaries, the experiences within these spaces were diverse, and not all performances were universally groundbreaking or progressive. Some were exploitative, even while others genuinely sought to challenge norms and broaden the scope of artistic expression. The legacy of these theatres remains complex and multifaceted within the broader context of the cultural and artistic history of the late-twentieth century. Certainly, the field of sex work and its intermedial effects with the theatre, music and the arts warrant further study, and above all, deserves more appreciation for the resulting works and myriad forms of artistic expression that resulted from it.

Notes

[1] Edmund White, ‘Why Can’t We Stop Talking About New York in the Late 1970s?’, 10 September 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/10/t-magazine/1970s-new-york-history.html (accessed January 5, 2024).

[2] Dixie Evans, interview with the author, 26 July 1998.

[3] V. R. Macbeth, ‘The Great White Way’ , 26 September 2006, https://web.archive.org/web/20110504160457/http://timessquare.com/NYC__/Times_Square_History/The_Great_White_Way/ (accessed December 23, 2023).

[4] This description is based on the author’s observations of Times Square during the late 1970s and the 1980s, while living in New York City.

[5] William B. Lockhart (ed), The Report of the Commission on Obscenity and Pornography (New York: The New York Times Company, 1970), pp. 614-23.

[6] ‘Memoirs v. Massachusetts, 383 U.S. 413’ (1966), https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/383/413/, (accessed 16 December 2023).

[7] ‘Prostitution Laws in New York State’, in Melissa Hope Ditmore (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Prostitution and Sex Work, Vol. 2 (Westport: Greenwood Press, 2006), p. 648.

[8] ‘The Porn Prince of New York’s Live Sex Shows’, 11 February 2020, https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-porn-prince-of-new-yorks-live-sex-shows-in-1970s-times-square (accessed 19 December 2023).

[9] In the late 1970s I habituated these venues with my boyfriend at the time, who danced at the Gaiety theatre and other venues. This descriptive text of the sex theatres that catered to gay men is from first-hand experience in these establishments.

[10] Katherine Frank, ‘Stripping’, in Ditmore (ed), Encyclopaedia, pp. 466-67.

[11] Jonathan Soffer, Ed Koch and the Rebuilding of New York City (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), pp. 271-272.

[12] Soffer, Ed Koch and the Rebuilding of New York City, p. 272.

[13] ‘Sex Scenes: When Strip Clubs Were the Heart of Times Square’, 23 November 2018, https://garage.vice.com/en_us/article/59v9x3/sex-scenes-times-square, (accessed 19 December 2023).

[14] ‘Times Square’s Most Outrageous Sex Show, the Queen of Shock Rock, and the Svengali’, undated, https://www.therialtoreport.com/2019/08/18/monica-kennedy/ (accessed 20 December 2023).

[15] “‘Times Square’s Most Outrageous Sex Show’.

[16] Annie Sprinkle, Post-Porn Modernist: My 25 Years as a Multimedia Whore (San Francisco: Cleis Press Inc, 1998), p. 79.

[17] Sprinkle. Post-Porn Modernist, pp. 81-82.

[18] Tony Zanetta, telephone interview with the author, Bruvoll, Norway, 23 December 2023.

[19] Zoe Hansen, telephone interview with the author, Bruvoll, Norway, 19 December 2023.

[20] Wendy Chapkis, Live Sex Acts: Women Performing Erotic Labor (New York: Routledge, 1997), pp, 76-82.

[21] Samuel R. Delany, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue (New York: New York University Press, 1999), pp. 17-18.

[22] ‘The Porn Prince of New York’s Live Sex Shows’.

[23] ‘Times Square’s Most Outrageous Sex Show’.

[24] Chapkis, Live Sex Acts, pp, 109-10._

[25] ‘Times Square’s Most Outrageous Sex Show’.

[26] ‘Times Square’s Most Outrageous Sex Show’.

[27] Matt Adams, Hustlers, Escorts, and Porn Stars (Las Vegas: Insider’s Guide, 1999), pp. 26-27.

[28] Penny Arcade, telephone interview with the author, Bruvoll, Norway, 13 December 2023.

[29] Lydia Lunch, telephone interview with the author, Bruvoll, Norway, 15 December 2023.

[30] ‘Acker Awards New York: Biographical Notes on Kathy Acker’, undated, https://nyackerawards.info/kathy-acker/about.html, (accessed December 23, 2023).

[31] ‘The Woman of The Misandrists’, https://www.sissymag.de/die-misandristinnen-ueber-susanne-sachsse-viva-ruiz-und-kembra-pfahler/, 2 November 2017 (accessed 23 December 2023)

[32] There are many articles and books published on Times Square’s renovation after the 1980s, and I can recommend “Ed Koch and the Rebuilding of New York City” by Jonathan Soffer (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012) for further reading.