Making Michael Field

Guest post: Gareth Brookes (Kingston University)

… The rest

Of our life must be a palimpsest —

The old writing written there the best.

In the parchment hoary

Lies a golden story,

As ‘mid secret feather of a dove,

As ‘mid moonbeams shifted through a cloud:

Let us write it over,

O my lover,

For the far Time to discover,

As ‘mid secret feathers of a dove,

As ‘mid moonbeams shifted through a cloud!

Michael Field – ‘A Palimpsest’, in Wild Honey from Various Thyme (1908)

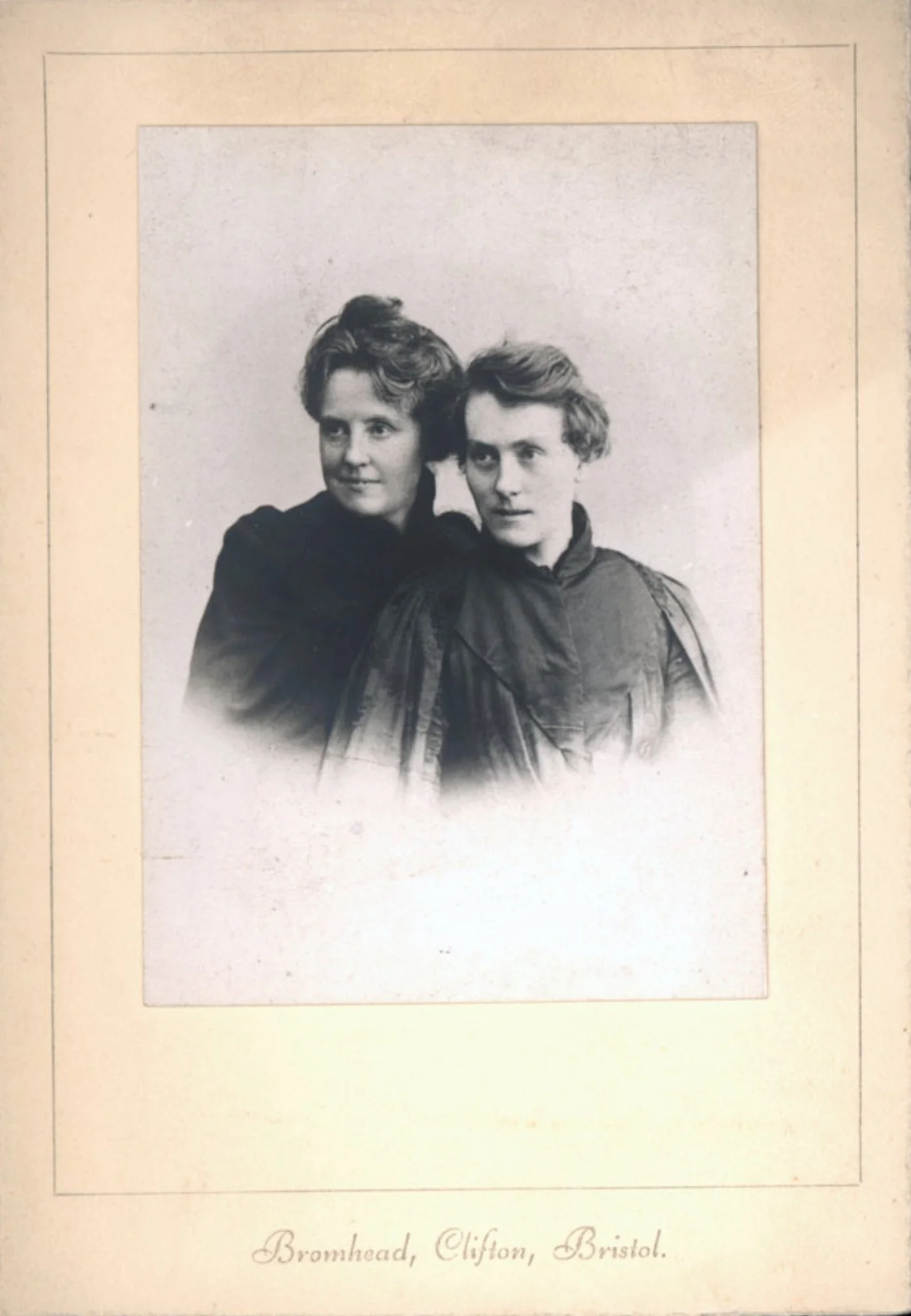

In 2025 I undertook a Visiting Research Fellowship in the Creative Arts at Merton College, Oxford University, in which I responded to the archives of Michael Field held in the Bodleian Library special collections through drawing and visual narrative. The project resulted in an aca-zine (academic zine), which I called Written Over for the Far Time to Discover (2025).

In the time spent with their archives I became thoroughly obsessed with Michael Field as a paradoxical construction and palimpsest. The figure of Field is an assemblage of multi-layered contradictions that represent an invitation to activity, a contradictory compulsion to separate the components of Michael Field whilst also constructing Field as an identity. Field is written over each time they are studied, each version inevitably marked by the subjectivity of the scholar, each iteration building a fresh Michael Field.

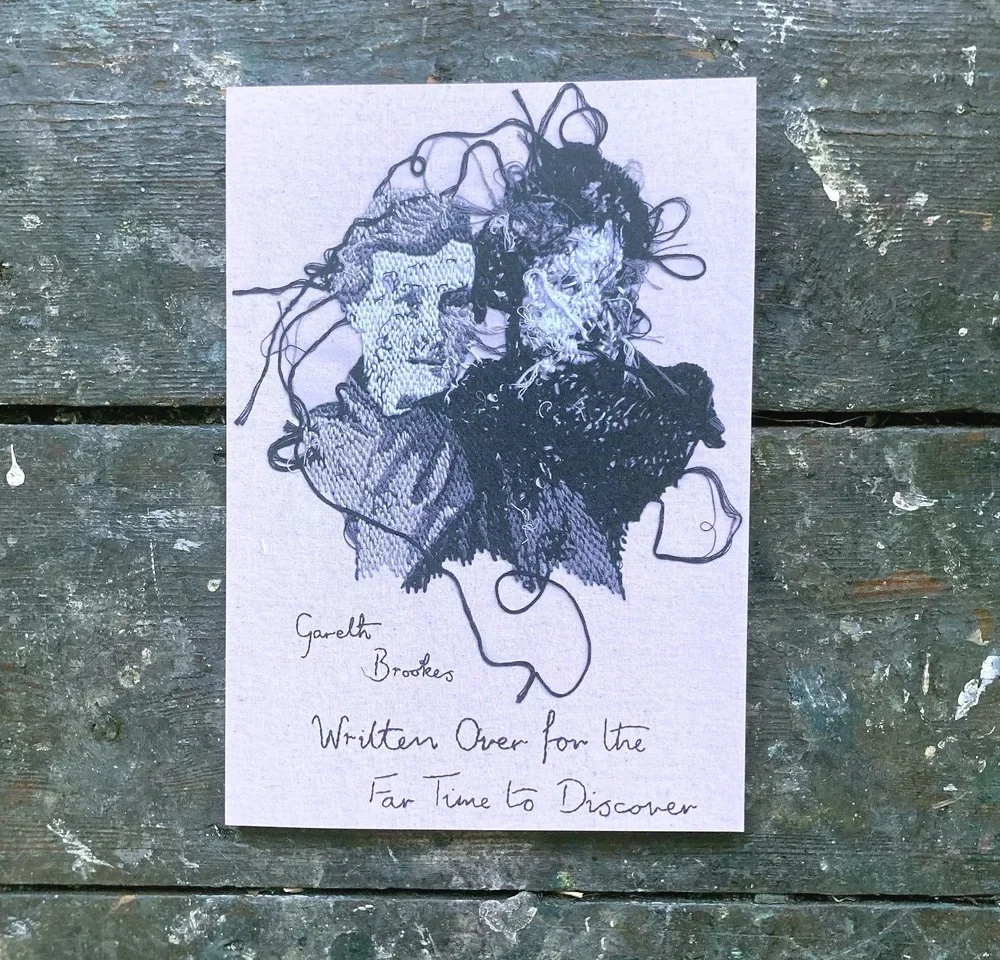

On one level the reasons for this are obvious. Field themselves did not represent a subjectivity. Michael Field was the pseudonym of two Victorian women: Katherine Bradley, and Edith Cooper (Fig. 1). These women worked together, collaboratively, on poetry, plays, and the monumental 28 volume life writing project Works and Days (1933). They regarded this collaboration as a physical and spiritual marriage.

Fig. 1: Clifton Bromhead, Michael Field (Katherine Bradley 1848-1914 and Edith Cooper 1862-1913). Photograph. Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, University of Delaware Library, Museums and Press, 1884-89.

Field were lovers and relatives. Bradley and Cooper were aunt and niece with a sixteen-year age gap between them. They remained together throughout their lives, a relationship whose consistency seems to owe as much to their artistic and familial connection as their romantic attachment. Field were a patchwork of contrasts and paradoxes. They lived a deeply radical, queer, and feminist life, but eschewed all forms of activism. They had many obsessive, often heterosexual, relationships and infatuations, but always saw themselves as an inseparable unity. They called one another Michael (Bradley) and Henry (Cooper), and referred to one another using the male pronoun, yet they were scornful of masculine traits in other women. Their domestic life re-imagined rather than subverted Victorian marital institutions. Their early paganism and Elizabethan obsessions, which they mined for the raw materials of their writing and queer inspiration, was replaced later by Catholicism. Field also occupied either side of the 19th and 20th Centuries: two eras that we tend to think of in contrasting terms. Their 19th century literary circle, which included Oscar Wilde and A. C. Swinburne, was replaced by figures such as Roger Fry and the Bloomsbury group, with connections to W. B. Yeats and Virginia Woolf. As Sarah Parker argues, this makes Field one of the few literary survivors of the 19th century decadents, going on to influence modernists in the 20th Century. [1]

These seeming contradictions and reversals add to the Field enigma. One of the first images I produced was an embroidery (Fig. 2), which I worked on from both sides, allowing the loose thread from the double facing representations to become entangled.

Fig. 2: Michael Field double sided embroidery. Image by and courtesy of Gareth Brookes. © Gareth Brookes (2026).

I thought of this image as a metaphor for Field as a combined subjectivity, but I soon realised that theirs was a complex conversation between two very different people. Cooper’s and Bradley’s writing did not fit a set pattern of collaboration, with pieces being worked on together and separately. The figure of Michael Field emerges most clearly in conversation and in conflict. This is most evident in their journals (the very essence of which contradict the secretive nature of diary-keeping) which record the couple often at odds as well as in accord.

This led me to think of Michael Field as a collaborative performance. As Carolyn Dever argues, Field was a pseudo-identity that relied on a third party such as Robert Browning, Oscar Wilde or Bernard Berrenson to bear witness to its performance. [2] Since their deaths the role of triangulating third party has included an increasing number of scholars who bring their own new constructions to the Michael Field activity. Many of these are as interesting and enigmatic as Field themselves. They include: Mary Sturgeon, Field’s first biographer, who died in mysterious circumstances; Thomas Sturge Moore, who took on the task of managing the Field’s literary estates alongside generations of his descendants; and the eccentric Ivor C Treby – poet, artist, collector of sand, and one of the first gay literary activists – who worked extensively on Field throughout the 1990s. Today the area of Field Studies has grown, and dozens of scholars contribute to the ongoing construction of Field. This is evidenced by the recent collection Michael Field in Context (2025), edited by Sarah Parker, which brings together 35 essays from academics working across a wide variety of disciplines.

I am a fine art trained graphic novelist with a PhD in Comics Studies. I first became aware of Michael Field when my research into haptic visuality in comics led my supervisor Dr Ian Horton to suggest Bernard Berenson as an example of the development of early theories of visual tactility. Horton mentioned the story of a strange poet in Berenson’s circle whose name I wrote down and forgot about for several months.

While it may seem strange to approach the archives of Field from the perspective of comic and zine scholarship, this relatively new area of academia can generate insights into issues central to Field as a figure and a writer, and offers ways to respond to Field’s ekphrasis, queer temporality, materiality, and imaginative tactility. I have developed theoretical approaches to this last point in my forthcoming monograph Reading Comics Through the Body. [3] In this book I argue that the mimetic technologies that modern comics use to appropriate materials from the world of tactile experience can constitute a haptic register of communication. In my graphic novels I digitally collage materials such as embroidered and pyrographed fabric, linocut prints, and pressed flowers. The imaginative sensual relationship with material traces that these techniques encourage is termed ‘haptic visuality’ by film scholar Laura U. Marks, and is theorised as inter-constitutive and erotic. [4] One of the connections between my practice and that of the Michael Fields is a relationship to decadent ideas of sensuality, excess and artificiality expressed through the visuality and tactility of their writing.

This is most clearly manifested in their ekphrastic collection Sight and Song, published in 1892. This collection attempted to translate the experience of looking at certain renaissance paintings into verse to capture ‘what certain pictures sing in themselves’. [5] In these poems the temporality of written narrative adds to the temporal sweep of the painting, staging movement and narrative within a still image. This led me to think about the function of imaginative animation, both in Field’s writing, and in my chosen field of visual narrative. Imagining their writing being acted is something Field would have been accustomed to. Bradley recorded herself and Cooper’s occupation as ‘dramatic authors’ in the 1901 census, and they published many verse dramas and plays. The Victorian concept of theatrical performance is ingrained in the foundational conception of many different forms of media, and comics are no exception. Ally Sloper, the first comic book character, described by one newspaper in 1896 as the most famous fictional character in Britain, [6] was the creation of music hall actress Marie Duvall, and appeared on the stage and in puppet shows as much as he did in print. Comics theorist Gerant D’Arcy highlights the close connection between comics and theatre in his development of the 19th Century idea of theatrical mise-en-scène as a way of framing the ‘stage’ of ‘paper actors’. [7] Field’s imaginative animation of artworks is found in letters in which Bradley witnesses the sculpted breast of the Ilaria del Carretto, ‘heaving like a low wave of the sea’. [8] This mirrors the writing of other decadents who seemed to share a fascination for stone sculpture becoming suddenly animate, perhaps most famously evidenced in Swinburne’s ekphrastic poem Hermaphroditus (1863), in which the poet beseeches the sculpture to ‘Lift thy lips / turn round, look back for love’. [9] Similarly, Walter Pater writes about sculpture in terms of ‘suddenly arrested life’. [10]

Book arts scholar Johanna Drucker suggests that the page of the book is another still surface that the reader can animate into life in a way that can be conceptualised as performance. [11] Drucker develops this idea from a recognition that words and letters on a page are images possessing materiality and form. The page is considered as a space upon (and between) which these images can ‘perform’, i.e., move, resonate, interact, and fulfil functions and action. In this performance the reader is active in controlling many elements, including the pace of the performance through their gaze and embodied action. This idea is developed through a consideration of concrete poetry, a form that traces its roots to Stéphane Mallarmé. Mallarmé’s use of visual typography and layouts, and art for art’s sake philosophy, influenced decadent publishing and is particularly present in Field’s books, in which elaborate borders and typography by artists such as Selwyn Image and Charles Rickets produce dense, animative entanglements of image and text.

As I drew, read, and interacted with Fields letters, I began to think of the performance of the page not only in terms of theatrical action, but also in terms of the performance of the drawing and writing body. The visual narratives included in my zine attempt to activate a third area of performance: the imaginative performance of the reader interacting through imaginative touch with the simulated materiality evident on the surface of the page. As I discovered, this mode of interactive sensual performance is present in Field’s approach to publishing in works such as Whym Chow Flame of Love, posthumously published in 1914 in a run of only 27 copies. The materiality of the soft russet cover is intended to reproduce the tactile experience of their beloved dog’s fur. This space of performance relies on an erotically inter-constitutive imaginative engagement, which, in its sensuous appeal and its reaching back toward past forms of encounter through artificial means, is heavily relatable to the features of decadence. This is a fertile method for exploring Field’s archives, in which the interplay of touch, and the traces left by touch, reveal insights into Cooper’s and Bradley’s aesthetic and collaborative practice.

The apparent triangulating effect of studying the intersubjective project of Michael Field led me to think carefully about the form my work would take. With successive scholars constructing their own Michael Fields, I began to conceive of Field scholarship in terms of fandom. In Fandom as Methodology (2019), Catherine Grant and Kate Random Love describe the fan-scholar as ‘a figure that has been theorised in fan studies to describe the overlapping positions of fans and academics’. [12] The fan-zine as an expression of fandom allows for a methodology enabled by the zine as an alternative form of academic writing, offering the possibility of non-authoritative scholarship presented as a contribution to a community of fan-scholars. This framing of the project offered a further way of exploring the ideas of tactility, embodiment, and co-affect. Zine theorist Alison Piepmeier notes that the initial motivation of zine making is to make handmade gifts for friends to reinforce, through materiality, an ‘intimate connection’. Piepmeier writes:

rather than positioning readers as consumers, as a marketplace, the zine positions them as friends, equals, members of an embodied community who are part of a conversation with the zine maker, and the zine aesthetic plays a crucial role in this positioning. [13]

Piepmeier argues that traces of embodied materiality in a zine invite an embodied response in the reader in the form of reciprocation of handmade objects such as letters and gifts, in a way that is directly proportionate to the handmade-ness of the initial zine. This exchange offers a route towards a more sensual form of academic publishing that allows enthusiasm and generosity to flourish through a non-hierarchical mode of knowledge exchange. It is, in addition, an appropriately decadent mode of scholarship, as it privileges the sensual excess manifested in a backward-looking form of information exchange, giving full expression to the passion of fandom. It led me to think about further zine-making approaches to incorporate in my project, and so, while my aca-zine was at the printers I visited a zine-making friend and exchanged time on their badge-making machine for beer. I made a hundred Michael Field badges in three versions to give away with the aca-zine, one depicting Field’s bramble logo, and two depicting their dog Whym Chow (Fig. 3). These signs are markers of fandom, and will be recognised only by true Field aca-fans.

Fig. 3: Michael Field badges. Image by and courtesy of Gareth Brookes. © Gareth Brookes (2026).

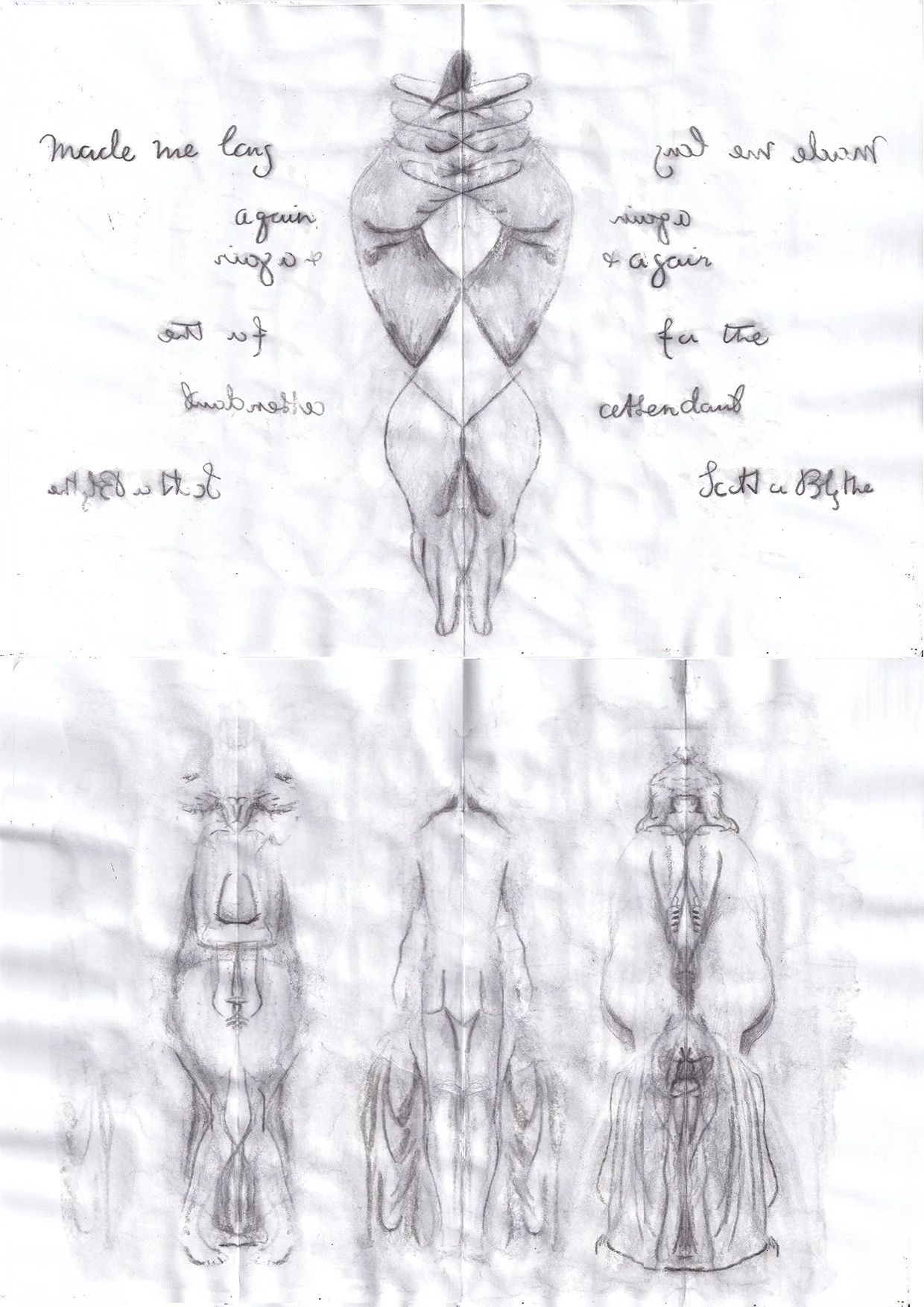

Fig. 4: Gareth Brookes, page from Written Over For the Far Time to Discover (2025). Aca-zine. Image by and courtesy of Gareth Brookes. © Gareth Brookes (2026).

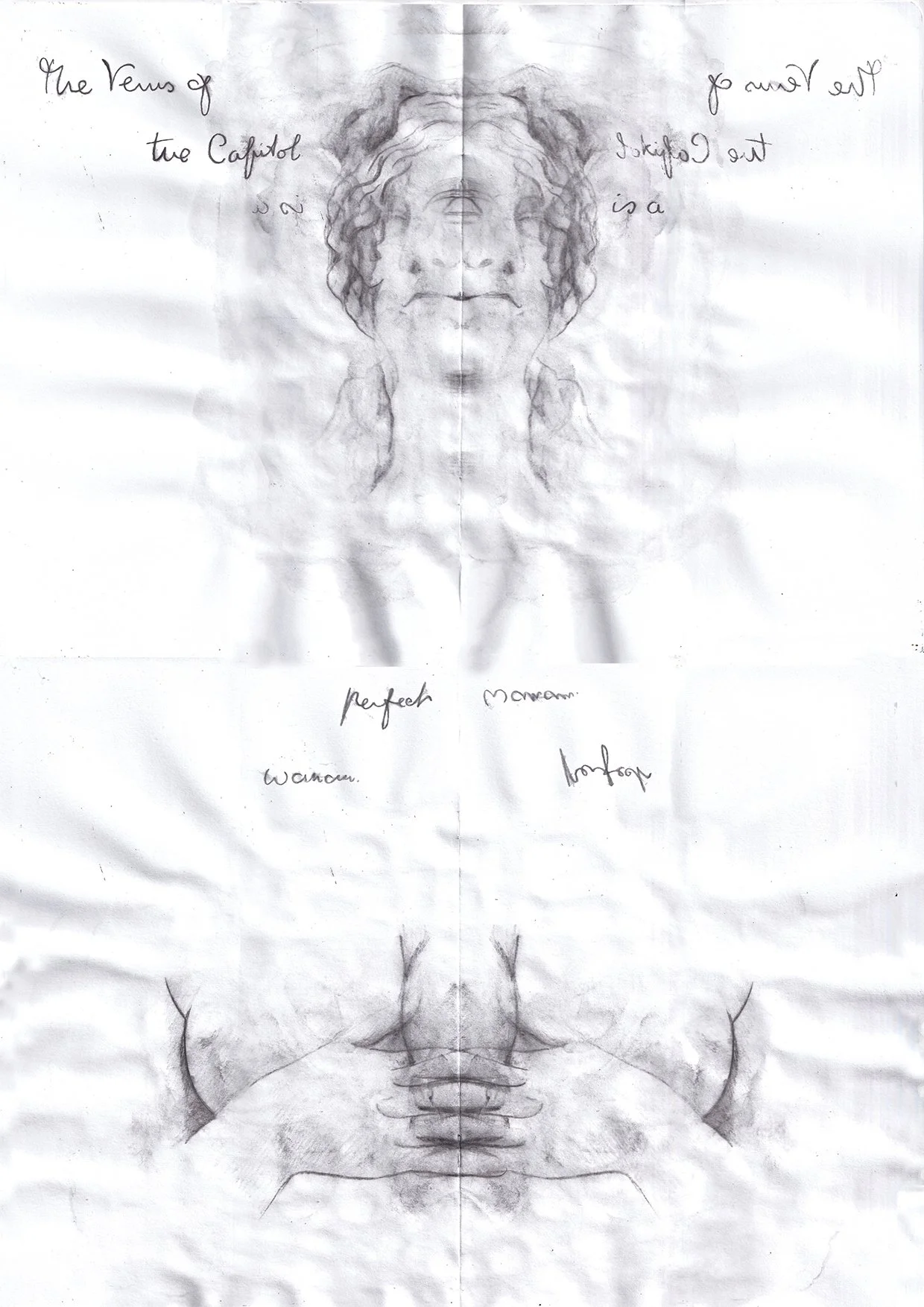

To give a further and more detailed example of how these ideas manifested themselves in my project I will now discuss a visual narrative that emerged in response to a series of love letters in the archive, written by Bradley to the teenage Cooper, which described sculpture in haptic and erotic terms heavily suggestive of imaginative touch and animation. The letters represent a co-affecting ekphrastic exchange as formative to the development of Field as a collaborative practice. Ana Parejo Vadillo has argued that this exchange mediated the burgeoning erotic relationship between Bradley and Cooper, the sculptures acting as proxy bodies upon which the pair could project erotic identification. [14] As Sharon A. Bickle argues, women’s letters in general and Cooper and Bradley’s in particular are performative acts of self-fashioning. [15] Through these letters, and their appeal to touch, Cooper and Bradley were able to practice, at a distance, a literature of tactility and exchange of tactile traces.

In one letter Bradley writes of viewing the Capitoline Venus in Rome:

Most happily her garments are beside her, not on her, and the lovely form from throat to foot is unmutilated and unshrouded, the dimpled back – the real beauty of the waist is only seen in the back – made me long again and again for the attendant… to turn the statue for me: and all the circling beauty of the lions Kept me in lingering adoration. [16]

Bradley is no less impressed by Ilaria del Carretto:

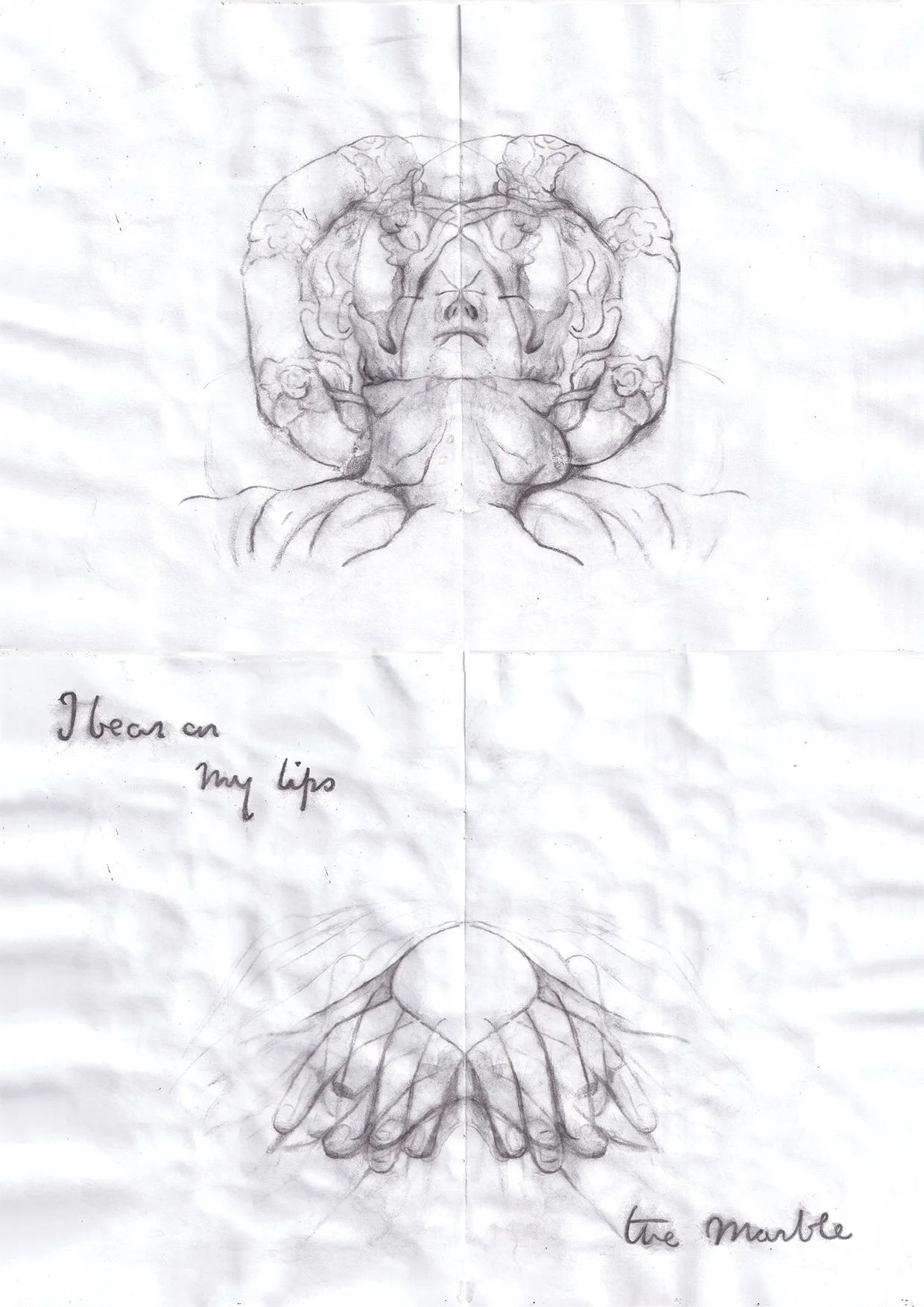

I bear on my lips the marble of Ilaria’s brow! … I kissed her on the calm forehead, the tremulously sweet lips, the sweet round chin. And I saw the breast ‘heaving like a low wave of the sea’. [17]

The materials I chose to respond to these letters invite imaginative tactility as a principal form of visual communication. Using water-soluble graphite, I produced double prints across folded paper pages. These folds suggest panels, the units of time in a visual narrative, and imaginatively enact the unfolding of paper involved in reading letters in which the embodied trace of the other is revealed to the eye (fig 5). This is intended to articulate an erotic tension produced by exchanges of tactile traces facilitated by the Victorian postal service. As Kate Thomas argues, this new network reframed the 19th century conception of touch and desire: ‘No one had to touch each other… In fact, not touching was part of the desire. If communication is about getting in touch, it is also very much about being pleasurably, desiringly out of touch’. [18]

Fig. 5: Gareth Brookes, page from Written Over For the Far Time to Discover (2025). Aca-zine. Image by and courtesy of Gareth Brookes. © Gareth Brookes (2026).

The drawings produced unpredictable arrangements of lines as the wet graphite exchanged traces across the folded paper. My copies of the hands of the Capitoline Venus in particular, which are busy hiding Venus’ modesty from the gaze of the viewer, find themselves clasping together, performing an exchange of touches, combining with Bradley’s words to produce new meanings (fig. 6 and fig. 7). These words are also copies I made by miming Bradley’s handwriting, which Ivor C. Treby calls ‘The great thorny Michaelian script’. [19] While at first I found Cooper and Bradley’s handwriting difficult to decipher, through copying I became accustomed to the handwriting of the two poets. I noticed Bradley’s habit of making words trail downwards to fit them on the line, and Cooper’s florid joining of letters together. In their journals they cross out and write over one another. Sometimes they seem to adopt one another’s habits, and at times it is impossible to know which one of them is writing. Treby writes that ‘even after a long acquaintance with the two scripts, it is still possible to pause at a transitional autograph, where a “Michael Field” person seems about to emerge’ [20].

Fig. 6: Gareth Brookes, page from Written Over For the Far Time to Discover (2025). Aca-zine. Image by and courtesy of Gareth Brookes. © Gareth Brookes (2026).

My inhabiting of the trace of Cooper and Bradley represents another kind of performance. In Traces en cases (1993), Phillipe Marion proposes the term ‘graphiation’ [21] to describe a coincidence of the gaze of the viewer/reader and the creative movement of the body of the artist. Marion argues that the traces of the body apparent in a drawing invite the reader to enter an imaginative engagement in which they put themselves in the place of the artist who drew the work, imaginatively re-tracing the actions of the artists and re-animating the movements of their body. This leads to a form of identification much like the identification of a spectator of a movie with the actor protagonist. Re-enacting the performance of these traces through the movements of my body exceeds this identification and resembles Elisabeth Freeman’s conception of erotohistoriography. This form of encounter with the past is ‘distinct from the desire for a fully present past, a restoration of bygone times’, and instead encounters the lost object fully in the present using ‘the body as a tool to effect, figure or perform an encounter with archives’. This practice admits embodied responses to archival material, and ‘sees the body as a method’. [22]

Spending time with Cooper and Bradley’s letters and the retracing of their movements through the copies I made suggested methodologies of achieving intimate touching points through time. Michael Field as an activity is an innovative exchange between distant temporalities. Cooper and Bradley’s decadent rejection of the age in which they lived led them to search the past for forms through which they could express themselves. As Kate Thomas argues, this ‘sense of being out of sync is itself a powerful erotics’, a temporal dislocation that ‘derives not only from the feeling of being out of step with their era but also from their awareness that their own incestuous partnership was built across familial sameness and generational difference’. [23] This dislocation and reaching back toward the past was combined with a strong belief in their destiny as poets ‘for the far time to discover’, a belief instilled early on by their mentor Robert Browning, who prophesised they would make their mark as poets but advised them to ‘wait 50 years’ for the moment to be right. 150 years on and Browning’s prediction may be coming true. Michael Field have never been more active. Field continues to be written over in our participatory age through the diverse constructions of aca-fandom and tactile palimpsestic exchanges with the past.

Dr Gareth Brookes is a graphic novelist, academic and Lecturer in Illustration Animation at Kingston University. His monograph Reading Comics Through the Body (2026) is published by Palgrave. He has published four graphic novels including The Dancing Plague (SelfMadeHero, 2021), and contributed to the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, Studies in Comics and Memory, and Mind and Media Journal.

Notes

[1] Sarah Parker, Michael Field in Context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2025), p. 273.

[2] Carolyn Dever, Chains of Love and Beauty, The Diary of Michael Field (Oxford: Duke University Press, 2022), p. 15.

[3] Gareth Brookes, Reading Comics Through the Body (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2026).

[4] Laura U Marks, Touch: Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002).

[5] Michael Field, Sight and Song (London: Elkin Mathews and John Lane, 1892): preface.

[6] Roger Sabin, ‘Ally Sloper: The First Comics Superstar’, in A Comics Studies Reader (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009), pp. 177-89 (p.185).

[7] Gerant D’Arcy, Mise en scène, Acting, and Space in Comics (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020) p. 9.

[8] Letter from Katherine Bradley to Edith Cooper, 26 August 1880. Bodleian Special Collections. Box no: MS. Eng. Lett. C. 418.

[9] Algernon Charles Swinburne, ‘Hermaphroditus’, in Poems and Ballads (London: Savill and Edwards, 1863), p. 91.

[10] Stefano Evangelista, ‘Walter Pater and Aestheticism’, in Norman Vance and Jennifer Wallace (eds) The Oxford History of Classical Reception in English Literature. Volume 4: 1790-1880 (Oxford University Press, 2013), p.38.

[11] Johanna Drucker, Figuring the word: Essays on Books, Writing, and Visual Poetics (New York: Granary Books, 1998).

[12] Catherine Grant and Kate Random Love. (eds), Fandom as Methodology: A Sourcebook for Artists and Writers (London: Goldsmiths Press, 2019), p.12.

[13] Alison Piepmeier, Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism (New York: New York University Press, 2009), p.70.

[14] Ana Parejo Vadillio, ‘Sculpture, Poetics, Marble Books: Casting Michael Field’, in Sarah Parker and Ana Parejo Vadillio (eds) Michael Field: Decadent Moderns (Ohio University Press, 2019), pp.50-73.

[15] Sharon Bickle, ‘Michael Field’s Letters’, in Sarah Parker (ed), Michael Field in Context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2025), pp. 20-29 (p.21).

[16] Letter from Katherine Bradley to Edith Cooper, 7 September 1880. Bodleian Special Collections. Box no: MS. Eng. Lett. C. 418.

[17] Letter from Katherine Bradley to Edith Cooper, 26 August 1880. Bodleian Special Collections. Box no: MS. Eng. Lett. C. 418

[18] Kate Thomas, ‘On Being Too Slow, Too Stupid, Too Soon’, in Janet Hally and Andrew Parker (eds), After Sex? On Writing Since Queer Theory (London: Duke University Press, 2011), pp. 66-75, (p.71).

[19] Ivor C Treby, Michael Field Catalogue: A Book of Lists (Self-published by Treby through his De Blackland Press imprint, 1998), p.125.

[20] Ibid, p.125.

[21] Jan Baetens, ‘Revealing Traces: A New Theory of Graphic Enunciation’, in Robin Varnum and Christina Gibbons (eds), The Language of Comics: Word and Image (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi 2001), pp. 145-55 (p. 145).

[22] Elizabeth Freeman, Time Binds, Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010), pp.95-96.

[23] Kate Thomas, ‘What Time We Kiss, Michael Field’s Queer Temporalities’, GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 13 (2-3) (2007), pp. 327-51 (p. 342).