Decadent art and the end(s) of progress: Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, Lolly Adams, and Wangechi Mutu

Fig.1: Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, SMILE WITH ME (2025). © Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley. Courtesy of Serpentine Galleries Press.

In a fabulously hyperbolic essay, Jean Baudrillard rails against a generalised fixation on the myth of eternal growth. ‘We are living in a state of excrescence’, he says, ‘meaning that which incessantly develops without being measurable against its own objectives’.[1] This state is compared to ‘cancerous metastases […] grow[ing] rampantly instead of following an organized pattern of development’, with ‘atrocious uselessness’ its inevitable fate in a cluttered global marketplace.[2] Progress, having succumbed to the lure of economism, collapses into inertia. The fact that Baudrillard’s essay was published in 1989 is significant: a year that some thought marked ‘the end of history’.[3] For Baudrillard and many others, the fall of the Berlin Wall did not signal a moment of universal emancipation; it opened the floodgates to super-saturated and hypertrophied production.

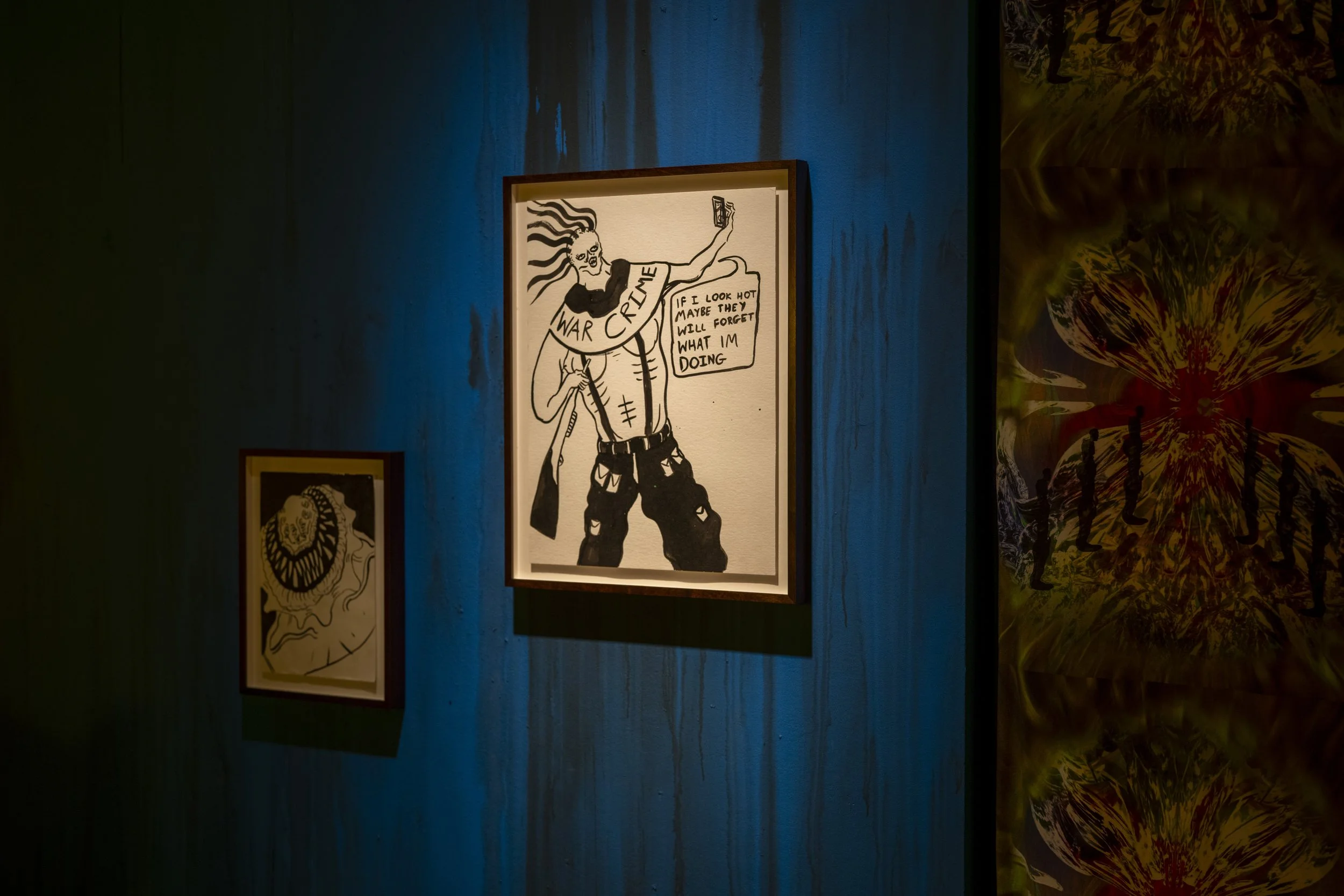

Fig. 2: Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, THE DELUSION (2025). Commissioned and produced by Serpentine Arts Technologies. © Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley. Photography: Hugo Glendinning. Courtesy of Serpentine Galleries Press.

I revisited Baudrillard’s essay shortly after heading to London’s Serpentine North to see Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley’s latest exhibition, THE DELUSION (2025). The show draws on the artist’s 2024 graphic novel Below the Blue Line (2024), which ‘unfolds in a near-future scenario where every negative online comment ever posted has become real’: an ‘apocalyptic event’ shaped by competing factions in a cacophonous culture war.[4] Best experienced in small groups, those gathered encounter screens populated with ethereal texts and entities, and are invited to participate in a suite of immersive gaming experiences rooted in the navigation of retro digital landscapes, each acting ‘as mirrors to society, utilising technology to foster civic participation’.[5] I wondered what Baudrillard might have made of it. On the one hand, it was staunch in its critique of liberal democratic progress, which is to say, the ruse of a neoliberal consensus. On the other, it remained steadfastly ‘progressive’. We are invited to query where ‘progress’ has gotten us, while holding out for the prospect that things might be other than they are.

A difficult balancing act, no doubt – and one that put me in mind of the antimonies of a ‘progressive’ decadence. Progress implies achievement, and decadence just the opposite: a perverse commitment to decay and entropy. Contrary to popular belief, decadence doesn’t refer to prolific acquisition. It is derived from the Medieval Latin word decadēre, meaning ‘to fall down’. It is also generally regarded as anti-instrumentalist – decadence and the useless go hand in hand – which would seem to suggest that decadence is not just an antonym for progress, but for progressiveness, too, if attempts to make art more inclusive and ethical are read in terms of ‘instrumental ambition’.[6] And yet, there are many – myself included – who recognise a peculiar resistance to the myths of economistic progress and eternal growth in some of the more thorny artworks that both lend themselves to decadence and refuse to slide ‘backward into a less progressive, closeted, and bigoted worldview’.[7] THE DELUSION is an example. It cherishes obsolescence and redundancy – its aesthetic is retro-techno – while holding on to the prospect of social and cultural change.

There are two main ways in which decadence tends to be understood once considered along the lines of the above. The first treats decadence as a pejorative or threat: decadence as degeneracy, and as a corrosive influence on art, culture, and society. Homophobia and racism are never far from this pejorative framing of decadence, as well as nostalgia for old-fashioned values. The columnist and cultural commentator Ross Douthat uses decadence in this sense in his book The Decadent Society (2020). For Douthat, ‘[t]he peak of human accomplishment and daring’ was in 1969 when the Americans put men on the moon – and it’s been downhill ever since, having lost site of our hunger for new frontiers as well as the heteronormative values that shore up the ambition and moral fibre of a nation.[8]

The interactive installations and cartoons peppered throughout The Delusion stage how decadence as terminal decline tends to be diagnosed by those who welcome certain forms of ‘progress’ (techno-scientific, economistic, expansionist) while remaining broadly critical of the ‘progressive’. However, they do so by refining a view that finds societal rot wherever it looks. In place of the latest technological innovation, we find game aesthetics and interactive platforms that delight in their own redundancy. We might see this as cohering with a second sense in which decadence is generally understood: decadence as the refinement of that which others might find distasteful.[9] The Delusion undoubtedly invites its audiences to invest in the idea of the ‘progressive’, but Brathwaite-Shirley seems to be just as interested in its darker undersides and enmeshment with progress as a grand narrative: how one set of progressive gains (for instance, off the back of feminist ideas and actions in the 1960s and 1970s that foreground biological essentialism) might come into conflict with another (e.g. the advancement of trans rights in more recent years), or what the implications of expansionism might be for different geopolitical communities, as well as the planet. The very idea of ‘progressiveness’ as a constant forward movement is put into question, just as ‘progress’ stumbles backward into an embrace of that which has been figured as obsolete and redundant.

Brathwaite-Shirley wades through what Bernard Stiegler once called ‘symbolic misery’ – the psycho-social effect of commodity-production that has reached a point of super-abundant stagnancy – but by wallowing in the miasma of that sphere, they intervene in its modus operandi: the 1s and 0s of ‘control societies’ that rely on a cluttered digital marketplace for survival. The invitation is to become involved once again in the production of symbols that are ‘as much the fruits of intellectual life (concepts, ideas, theorems, knowledge) as of sensible life (arts, know-how, mores)’,[10] drawing sustenance from the funk of digital deliquescence, and reclaiming at least some semblance of autonomy in a postdigital moment.

*

In Staging Decadence: Theatre, Performance, and the Ends of Capitalism (2023), I set out to address some of the issues that come with fixating on growth, progress, and intensified productivity as goals and signs of accomplishment. It looks at how performance makers have embraced ‘decadence’ as an art of falling and flowing away from these goals by refining what others might find distasteful, useless, or outmoded. It is an anti-productivist book. For theorists like Baudrillard and Kathi Weeks, productivism refers to the valorisation of intensified productivity regardless of tangible increases in meaningful output.[11] It also refers to a state of frenzied inertia that occurs when intensive productivity is introjected as a basis for self-realisation. There are important differences between the industrial capitalism that prompted decadent writers and artists in the 1880s and ‘90s to turn their backs on productivism,[12] and failing growth-oriented policies in our own ‘post-industrial’ present; nonetheless, the rejection of productivism is a decadent proclivity that is as relevant now as ever.

This may well smack of an idle aristocracy. Dave Beech critiques the imaginary that gives rise to the valorisation of idleness as irredeemably aristocratic or bourgeois,[13] but decadence, like any form of expression, is not inherently one thing or another. Kirsten MacLeod’s reflections on decadent writers from different backgrounds and their complicity with literary markets reveals how misleading it is to reduce decadence to the leisure class,[14] while Terry Eagleton acknowledges how Wilde’s aestheticism might align with aristocratic values just as it might provide the ‘instruments of their subversion’.[15] One might say that the very ‘point’ of decadence is to upend the tastes that underpin the stability of value attribution and the structures that perpetuate its normative codification.[16]

Like Brathwaite-Shirley, the multidisciplinary artist Lolly Adams (aka Miss HerNia) brings together the two senses of decadence highlighted above. More specifically, they approach decadence as a pejorative used to demean or undermine demographics associated with social and civilisational decline by embracing decadence as an artistic approach that falls away from tastes and values that have been socially sanctioned. Her kinetic installation Act One (2025) is a particularly relevant example, as it thematises class by way of decadent expression. Mugs depicting gurning faces spin on a wheel around a fuchsia polyurethane bust made from a mould of Adams’s upper body, all framed by vinyl wallpaper inspired by the facades of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice. A hose from the mouth draws water to a spout that makes the wheel spin round, endlessly. The work queers the Catholic iconography that scholars have associated with a decadent sensibility,[17] and pokes fun at the kinds of expectation that might surround its installation at London’s Royal Academy, where it was exhibited in 2025. It’s a piece that’s all about taste, but more than that it’s about class and cultural refinement. It’s what Adams calls ‘a working-class shrine’[18] in which aesthetic standards, civility, and cultural attainment are perverted, if we understand that term as a corruption of loftier standards.

Fig. 3: Lolly Adams, Act One (2025). Royal Academy, London. © Lolly Adams. Photography: Andy Keate. Courtesy of the artist.

When decadents queer aristocratic or bourgeois tastes and values, they critique the behavioural customs and expectations that come with them. They disturb civility and the civilising process. The context of the Royal Academy is particularly resonant here given its royal charter, and the conclave of artists memorialised in statues around the building. There is something Victorian in Adams’s Day-Glo death mask (I initially mistook it for the nineteenth-century Queen), and the gurning mugs – the products of Welsh pottery brand Pretty Ugly Pottery – are probably not what Joshua Reynolds had in mind when establishing a haven for an artistic elect. There is little by way of ‘refinement’ in these mugs, and yet the constellation of elements comprising Act One suggest that a considerable amount of time and energy has been invested in its meticulous composition. The hose spouting water from her double’s mouth mobilises a halo of pots that circulate around her own image – a tricky mechanism to get right – but instead of drawing us up to the lofty standards of a ‘royal’ academy, we encounter reverence for what Baudrillard dubs the ‘aberrant sanctification of work’, spinning endlessly and redundantly around and around and around.[19] In the middle is the artist-saint, completely inert – deathly, even – encircled by clunky perpetual motion. ‘Low’ decadence, no doubt, but decadence nonetheless, and of a kind that pastiches civilisational progress and culture, in the Arnoldian sense, as that which promises ennoblement and the elevation of mind, spirit, and society.

*

Paul Verlaine’s poem Langueur (1883) was much favoured by artists and writers associated with decadence in the 1880s and ‘90s. Translations vary, but its opening line – ‘I am the Empire at the end of decadence’ – captured a crepuscular mood at a time when industrial modernity was fundamentally transforming European cities like Paris and London. Time was speeding up, space was getting sparser, empires were extending their reach and influence – so perhaps the fall of Empires long past and the fatal ‘excesses’ of their rulers was as good a place as any to turn. Oscar Wilde had his hair cut in the style of Nero. Lawrence Alma-Tadema depicted Elagabalus and his guests drowned amid a deluge of rose petals. Artists and writers like these turned their attention backwards, not forwards, albeit counterintuitively given the fact that decadence might just as well be treated as the antithesis or perversion of classicism.

As Jane Desmarais and David Weir acknowledge, the fall of Rome is ‘the paradigm case’ of decadence as historical decline, and played a key role in how ‘the enlightenment project and the ideology of progress’ was imagined.[20] If the Roman Empire represents the pinnacle of imperial might, then its fall represents everything that progress and achievement shouldn’t be. Turning to the ancient world to interrupt or reimagine the present is not without risk (Spengler’s nostalgia for ‘Caesarism’[21] and Mussolini’s for imperial Rome informed the development of fascism); however, the point in doing so for many (but by no means all)[22] decadents was precisely to undo the idealisation of the ancient world as a powerful figuration of empire. Such decadents aren’t interested in the might of empires, but their corruption. This includes the depiction of emperors like Elagabalus who were vilified in accounts of the period that used demeaning fictionalisation to condemn how they ‘failed’ the imperialist project. Artists and writers who turned to the ancient world in developing decadent themes and styles – like Wilde, or more recently Jeremy Reed in his book Boy Ceasar (2004) – did so in the full awareness that they were landing on figures who were acknowledged as dangers to empire and all that it stood it for: strength, patriarchy, and the obliteration of values and embodiments that were seen to stand in its way.

Another way of approaching the linkages between empire, civilisation, and progress is to take the more disparaging sense of decadence at face value – to recognise decadence as a threat – but to do so in ways that do not target individuals, but ideologies and powers of oppression. Yinka Shonibare and Hew Locke wield decadence in this way, as does the Kenyan American artist Wangechi Mutu. In her animated video The End of Eating Everything (2013), a ‘pharaonic’[23] woman with tentacular hair moves slowly across the screen – graciously at first, but soon with venom as she approaches a flock of birds, apparently compelled to consume them, and with time revealing that she pulls behind her a gigantic, slug-like body comprised of what we might describe as the wreckage of history. Modelled on the musician Santigold (Santi White), this cyborgian figure is made to appear both ‘seductive and repulsive’.[24] We might see her as an embodiment of the devastation wrought by human progress, their body bloated and lesioned, but as Chika Okeke-Agulu argues, she is also a ‘justifiably enraged figure of the earth-land, whose natural capacity for generating and supporting life has been fatally compromised by anthropogenic forces’.[25] What lends Mutu’s film to a decadent sensibility is its rootedness in the damage wrought by capitalism, colonialism, and the pursuit of endless growth, and the ambivalence of the entity at its heart, who seems at once to embody and hasten planetary exhaustion.

Rethinking our attitude to growth might mean ‘growth agnosticism’,[26] ‘degrowth’,[27] or ‘post-growth’.[28] These positions range from the progressive to the radical, but what they share is a call to shed our ‘addiction’ to growth,[29] and to heed the reservations that Simon Kuznets expressed in the 1960s and ‘70s, thirty years on from devising a measure of gross national income, or what we now call Gross Domestic Product. For Kuznets, distinctions must be made ‘between quantity and quality of growth, between its costs and return, and between the short and the long run’.[30] Today, ‘[t]he costs of growth have been increasing faster than the benefits’.[31] The biggest cost of all is the exceeding of planetary limits, threatening a very different kind of end to the one faced by decadents in the 1890s: less fin de siècle than an all-too real ‘fin du globe’.[32] This has prompted some scholars to explore decadence as a way of approaching ecology: for instance, by cultivating a taste for non-human processes like fungal growths and the ‘phosphorescence of decay’,[33] or by developing eschatological theories that shift how we think about the end times as a totalising condition[34] – the ultimate milestone, and the inevitable outcome of unfettered growth.

The End of Eating Everything fizzes with the phosphorescence of decay. Lesions throb, and the gloss of the entity’s body inspires carnal thoughts of being touched and perhaps infected by putrid growths. It is a bloated monster – and yet one who is powerful enough to break free and transform into something else. At the end of the film the entity transmogrifies into innumerable spermatoid creatures modelled on Santigold’s head. They drift through a sky-blue miasma amongst cloud-like puffs of smoke. The end is ambiguous, but it does seem as though this is not the end at all, but a beginning – which is always the promise of decadence. Decadence luxuriates or languishes at cusps and transitions, and while ambivalent toward what might come ‘after’, its status implies the prospect of transformation. Here, it is not progress that we encounter – progress as a series of incremental changes – or even the clear-cut objectives of progressive sentiment, but a more radical investment in the dissolution of progress as a calculable process of domination, expropriation, and control.

Brathwaite-Shirley, Adams and Mutu invite us to shift how we come to understand what constitutes ‘progress’ at a time when productivism rules the day. Obsolescence and the retrograde are what they do best. Instead of submitting to expansionary logics of incessant growth and intensified productivity, they remain deeply invested in upending the values and infrastructures that enable some to benefit from the dying headwinds of progress, but not others. Some of the most interesting artistic practice isn’t the latest innovation but something that isn’t ‘of’ this time, or that jolts it out of joint. Brathwaite-Shirley’s fascination with redundant tech is an example, as is Mutu’s ecological interest in deep time, and Adams’s pastiche of class and labour dynamics in a major cultural institution. Works like these encourage us to embrace the decadent intransigence of art in the face of productivism, and to think of it as its greatest asset. Decadence delights in the outmode and refines decay, but that does not mean it is inherently regressive; in fact, such gestures might be the last bastion of radicalism, which would seem all the more compelling in times governed by the very real threat of apocalypse.

*

Dr Adam Alston is Reader in Modern and Contemporary Theatre at Goldsmiths, University of London. He runs the Staging Decadence project (www.stagingdecadence.com), and is Co-Deputy Chair of the Decadence Research Centre at Goldsmiths. He is the author of Staging Decadence: Theatre, Performance, and the Ends of Capitalism (Bloomsbury 2023), co-editor (with Professor Jane Desmarais) of Decadent Plays: 1890-1930 (Bloomsbury 2024), co-editor (with Dr Alexandra Trott) of a special issue of Volupté: Interdisciplinary Journal of Decadence Studies on ‘Decadence and Performance’ (Winter 2021), and author of several chapters and articles exploring decadence and performance. He has produced and curated performance events and club nights at venues including the V&A, Rich Mix, Iklectik, The Box, HERE Arts Centre (New York), and The Albany, and he has also published extensively on immersive and participatory theatres.

Notes

[1] Jean Baurdillard, ‘The Anorexic Ruins’, in Dietmar Kamper and Christoph Wulf (eds), Looking Back on the End of the World, trans. David Antal (New York: Semiotext(e), 1989), pp. 29-45 (p. 29).

[2] Ibid, pp. 29-30.

[3] Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (London: Penguin, 2012).

[4] Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, THE DELUSION, exhibition catalogue / zine. Presented at Serpentine North, 30 September 2025 – 18 January 2026. Edited by Tamar Clarke-Brown and Liz Stumpf (London: Serpentine, 2025), p. 6.

[5] Ibid, p. 7.

[6] David Weir and Jane Desmarais, ‘Introduction: Decadence, Culture, and Society’, in Jane Desmarais and David Weir (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Decadence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022), p. 12.

[7] Alice Condé, ‘Contemporary Contexts: Decadence Today and Tomorrow’, in Weir and Desmarais, Oxford Handbook of Decadence, pp. 96-114 (p. 98).

[8] Ross Douthat, The Decadent Society: How We Became Victims of Our Own Success (New York: Avid Reader Press, 2020), pp. 1-2.

[9] See David Weir, ‘Afterword: Decadent Taste’, in Jane Desmarais and Alice Condé (eds) Decadence and the Senses (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), pp. 218-28.

[10] Bernard Stiegler, Symbolic Misery, Volume 1: The Hyperindustrial Epoch, trans. Barnaby Norman (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2014), p. 10. Note that, elsewhere, Stiegler offers a staunch critique of what he regards as the decadence of capitalism, arguing that genuine innovation is in ‘opposition to decomposition’. Bernard Stiegler, The Decadence of Industrial Democracies: Disbelief and Discredit, Volume 1, trans. Daniel Ross and Suzanne Arnold (Cambridge and Malden, Ma: Polity Press, 2011), p. 95.

[11] See Jean Baudrillard, The Mirror of Production, trans. M. Poster (St Louis, MO: Telos Press, 1975); Kathi Weeks, The Problem with Work: Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork Politics, and Postwork Imaginaries (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

[12] For a study of Wilde as an anti-productivist writer, see Carolyn Lesjak, ‘Utopia, Use, and the Everyday: Oscar Wilde and a New Economy of Pleasure’, ELH, 67 (1) (Spring 2000), pp. 179-204 (p. 181).

[13] Dave Beech, Art and Postcapitalism: Aesthetic Labour, Automation and Value Production (London: Pluto Press, 2019), p. 81 and pp. 85-86.

[14] Kirsten MacLeod, Fictions of British Decadence: High Art, Popular Writing, and the Fin de Siécle (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

[15] Terry Eagleton, ‘Saint Oscar: A Forward’, New Left Review, 177 (Sept./Oct. 1989). Available at: https://newleftreview-org.gold.idm.oclc.org/issues/i177/articles/terry-eagleton-saint-oscar-a-foreword, accessed 6 August 2025.

[16] This is also what differentiates the view of decadence set out here from the pseudo-Epicureanism promoted by the business-savvy editor of Idler magazine, Tom Hodgkinson. Hodgkinson implores his readers to enjoy pleasure ‘while being happy with what you have’, as if one’s lot and willingness to be content with it were not inequitably distributed in the first place. Tom Hodgkinson, An Idler’s Manual (London: Idler Books, 2021), p. 9.

[17] See, for instance, Ellis Hanson, Decadence and Catholicism (Harvard University Press, 1997).

[18] Lolly Adams, ‘Act one & Act two’, Lollyadams.com, available at: https://www.lollyadams.com/act-one-act-two, accessed 5 August 2025.

[19] Baudrillard, The Mirror of Production, p. 36.

[20] Jane Desmarais and David Weir, ‘Introduction’, in Desmarais and Weir, Decadence and Literature, pp. 1-11 (p. 3).

[21] See Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West, Volume II: Perspectives of World-History, trans. Charles Francis Atkinson (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1980), p. 507.

[22] See Alex Murray, Decadent Conservatism: Aesthetics, Politics, and the Past (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023).

[23] Chika Okeke-Agulu, ‘Wangechi Mutu’s Ecofeminist Vision in The End of Eating Everything’, Journal of Contemporary African Art, 36 (55) (Nov. 2024), pp. 36-43 (p. 36); see also Okwui Enwezor’s nuanced discussion of Mutu’s work in ‘Weird Beauty: Ritual Violence and Archaeology of Mass Media in Wangechi Mutu’s Work’, in Friedhelm Hütte and Christina März (eds), Wangechi Mutu, Artist of the Year 2010: My Dirty Little Heaven, trans. Burke Barrett, Barbara Hess and Ralf Schauff (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2010), pp. 25-34.

[24] Franklin Sirmans, ‘Portfolio’, Grand Street, 72 (Autumn 2003), pp. 156-61 (p. 161).

[25] Okeke-Agulu, ‘Wangechi Mutu’s Ecofeminist Vision’, p. 39.

[26] Kate Raworth, Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist (Dublin: Penguin Books, 2022), pp. 29-30.

[27] The roots of ‘degrowth’ as a notion can be traced back to the early 1970s. See Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, The Entropy Law and the Economic Process (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1971); Ernst Friedrich Schumacher, Small is Beautiful: Economic as if People Mattered (London: Vintage, 2011); Club of Rome, Limits to Growth (S.I.: Earth Island Ltd., 1972); André Gorz, Nouvel Observateur, proceedings from a public debate organized in Paris by the Club du Nouvel Observateur, Paris, 19 June 1972. The early 2000s saw renewed interest in Gorz’s consideration of décroissance (degrowth), and since then the field has flourished. For an overview of key concepts, see Giacomo D'Alisa, Federico Demaria, and Giorgos Kallis (eds), Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era (Abingdon: Routledge, 2014).

[28] Timothée Parrique, Slow Down or Die: The Economics of Degrowth, trans. Claire Benoit (London: Profile Books, 2025), p. 16.

[29] Raworth, Doughnut Economics, p. 30.

[30] Simon Kuznets, ‘How to Judge Quality’, The New Republic, 20 October 1962. Available at: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5536fbc7e4b0d3e8a9803aad/t/554d19f6e4b0005c69696961/1431116278720/Kuznets_How+to+judge+Quality_1962.pdf, accessed 4 July 2025. See also Simon Kuznets, Population, Capital, and Growth: Selected Essays (London: Heinemann Educational Books, 1973), pp. 165-84 (pp. 182-83).

[31] Matthias Schmelzer, The Hegemony of Growth: The OECD and the Making of the Economic Growth Paradigm (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), p. 4.

[32] See Benjamin Morgan, ‘Fin du Globe: On Decadent Planets’, Victorian Studies, 58 (4) (Summer 2016), pp. 609-35.

[33] Dennis Denisoff, Decadent Ecology in British Literature and Art, 1860–1910: Decay, Desire, and the Pagan Revival (Cambridge University Press, 2022), p. 9. Denisoff is quoting Paul Bourget. See Paul Bourget, Essais de psychologie contemporaine, trans. Dennis Denisoff (Plon-Nourrit, 1908 [1878]), p. 19.

[34] David Weir and Jane Desmarais, ‘Introduction: Decadence, Culture, and Society’, in Desmarais and Weir, The Oxford Handbook of Decadence, pp. 1-17 (pp. 13-14).